The first two years of the Reagan Administration were difficult for most Americans. His 1981 cuts to security network programs led 6 million additional people to fall into poverty between 1980 and 1983. Together with an unemployment of almost 11% during his first mandate, Reagan ended up increasing taxes more than 10 times during his presidency to try to clean the disorder that his 1981 cuts made.

However, the elements of that economic devastation continue to chase us today. One of the most obvious examples is the explosion of camps of homeless people in the center of the nation, which began during the presidency of Reagan and led to the first federal legislative response to the lack of housing, in 1987.

Here we are almost four decades later: the country has its greatest number of homeless since the follow -up began, and the Republicans of the House of Representatives simply voted to reduce security programs. It is as if those years of Reagan do not teach them anything about cause and effect. Yes, we have a national debt of $ 36 billion, and Moody's just reduced our credit rating. We have to draw on the ropes of the bag for the good of our fiscal stability. But it matters where you make the cuts. Creating a scenario that can increase poverty and lack of housing is tremendously counterproductive.

Even reserving at the moment in human costs, the economic case to reduce the lack of housing is painfully clear.

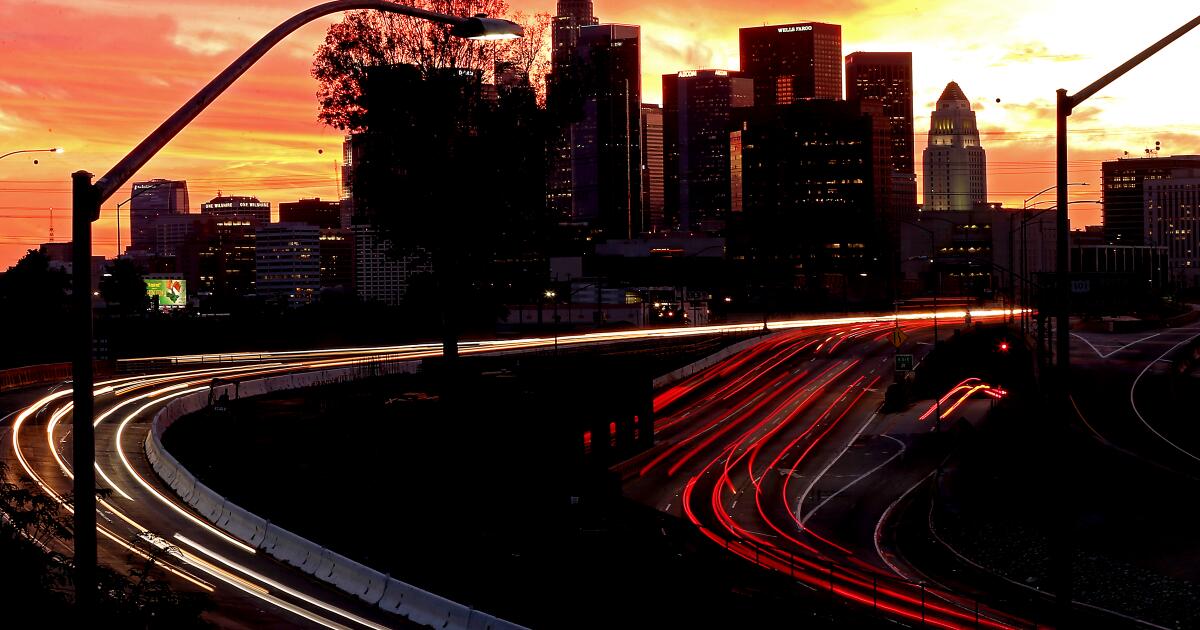

The commercial real estate value of our city centers erodes vacancies, and the center of Los Angeles suffers a rate of more than 30%, according to a recent analysis by Cushman and Wakefield. And that wealth will continue to flee from the center because people avoid the center. Because? Security concerns. Something about seeing a lot of buildings and tents addressed in the streets does not feel comforting.

A federal budget created to crush the most vulnerable people will expel American countless homes and streets. The vision of Republicans will create more camps, there is certainly no way to address public security concerns or revitalize the center.

It is impossible to make the United States great without taking care of its people first, all its people. All elegant shopping centers in the suburban world will not change that.

In the center of Los Angeles in 1983, Bullock's at 7th Street and Broadway closed their doors. That same year, Gimbels in New York said goodbye. And in my hometown of Detroit, the vast Hudson – second in size Only Macy's in New York, also closed.

That was not just a reflection of changing purchase habits. That was also a microcosm of economic erosion that was placing the heart of our cultural centers after those devastating budget cuts in 1981.

The best architecture of a municipality is often in the center. The best historical buildings are close to the courts and the main streets. When the United States was concerned about its center centers, whole cities and states prospered. We cannot afford to give up our urban centers. Local officials get that; Cities float and adjust cities in a perennial way in the hope of revitalizing these areas. But before elected officials are concentrated in eliminating the bureaucracy of the acquisition of liquor licenses or offering tax exemptions to possible developers, they must help people who sleep in the streets in front of the buildings that cities want to reopen. Until that happens, the economic potential of our center centers will remain in limbo.

Californians take this risk seriously. Matt Haney (D-San Francisco) leading a multiple layer initiative to revitalize the difficulty centers in California from the pandemic. For more than a year he met with mayors and other leaders from nine cities to identify the barriers for a prosperous center.

This week, Haney, who presides over the recovery committee of the Center of the Assembly, announced a package with 13 initiatives designed to return life to civic centers. Three of them are specifically directed to the lack of housing. As regards me, those are the only three that matter. If the public sector can get people out of the streets and shelters, the private sector will do the rest.

“I think cities now have the tools and legal clarity to effectively address the camps,” Haney told me this week. “They can clear persistent camps, but they also need to have places for people to leave.”

That last point cannot be ignored.

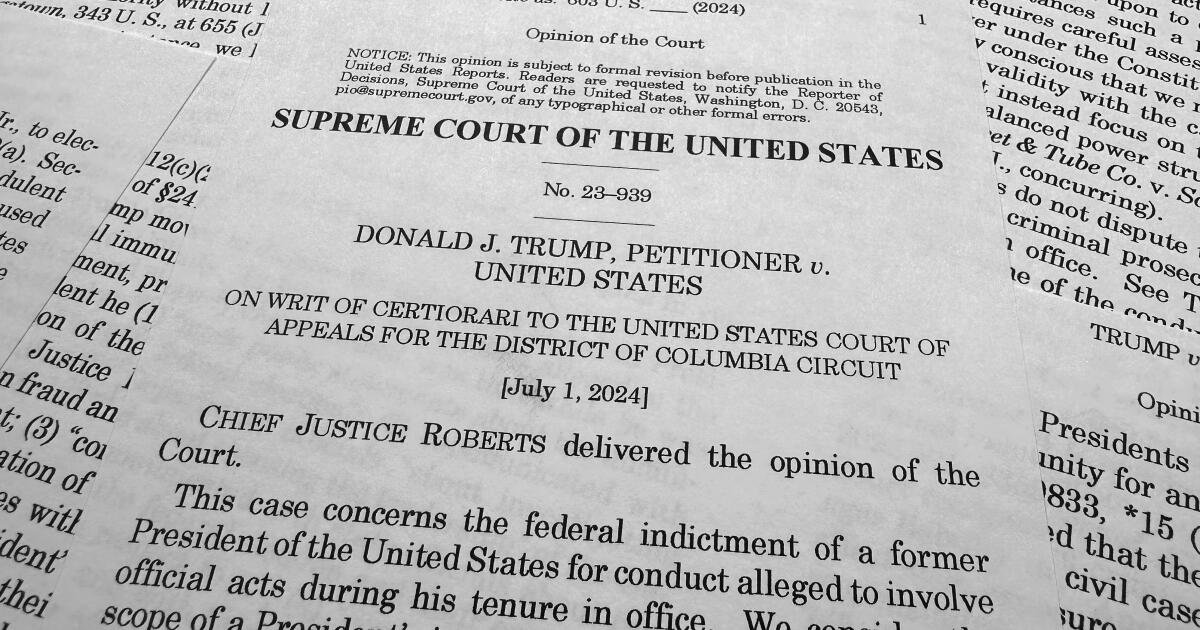

“The cities are now more focused on these short -term shelters and transition housing and ensuring that there are adequate locations,” said a crucial component since last summer the Supreme Court supported the power of cities in California and the West To break the camps, and this month, Governor Gavin Newsom has made that tactic a topic of conversation.

“What we do not want to see is to clarify a camp so that people get up and move two blocks away,” Haney added. “Nor does it make much sense to spend money to put someone in jail just because they have no home. That will not be a solution.”

His opinion is that the highest priority for the state government and for mayors should be financing for the “response to the lack of housing, which really focuses on eliminating the camps and making people enter.”

Obviously, that is easier to say it than to do it. But if that is not done, nothing else will work. Unattended people will have no way for the lack of housing, and our center will continue their death spiral.

@Lzgranderson