Book Review

Big Island

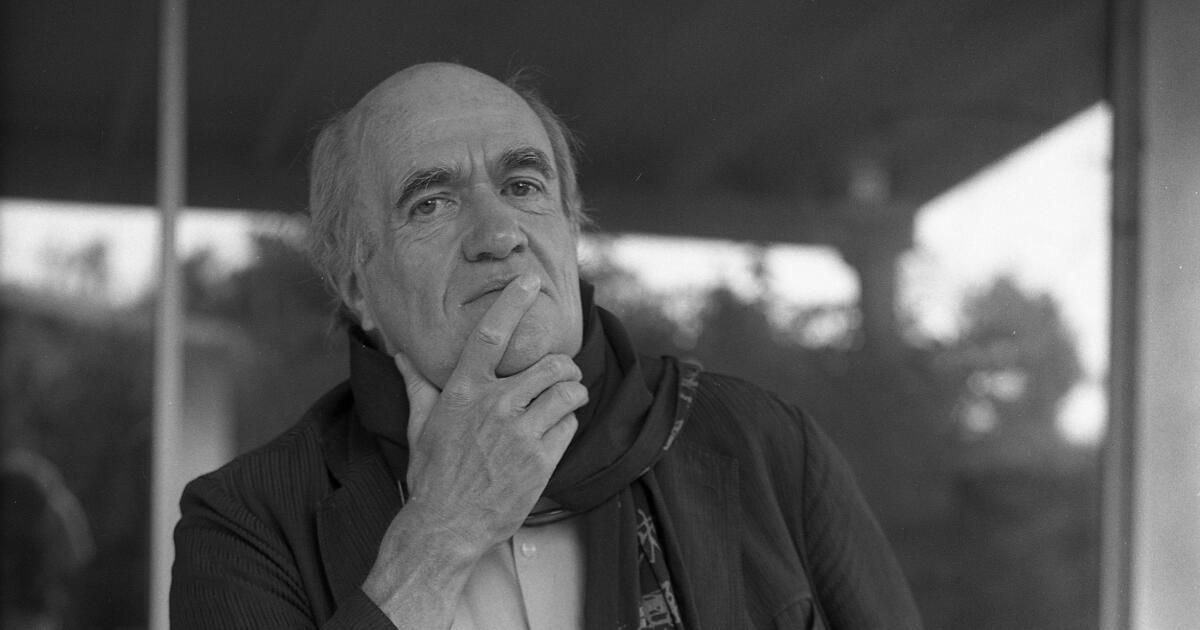

By Colm Toibín

Scribner Book Company: 304 pages, $28

If you buy books linked to on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

Colm Tóibín is not well known for his “hooks”, but he certainly has one here. The author, who specializes in the fictionalized lives of repressed literary masters with elaborate prose styles (Henry James in “The Master,” Thomas Mann in “The Magician”), returns in “Long Island” to his other register, the narrative deceptively simpler story of ordinary lives, and into familiar territory from his hugely popular book, the 2009 novel “Brooklyn” (which was later made into an equally popular film starring Saoirse Ronan and Domhnall Gleeson).

Ah, that hook. Eilis Fiorello, née Lacey, opens the door of her Long Island home to a stranger who tells her that her husband, Tony, a plumber, “did a little more than estimated…and his plumbing is so good that [the man’s wife] “It's having a baby in August.” As soon as the child is born, the man says, he will deposit it at the Fiorellos' doorstep.

The problem, among others, is that Eilis will not have the baby at home either.

“What is plot in a novel?” Tóibín said. “An action that has consequences, which should not be predictable.” What makes “Long Island” especially rich (and doubly suspenseful) is that, along with the consequences of Tony's infidelity, the story is haunted by the consequences of the actions taken in the heartbreaking finale of “Brooklyn.” .

It is not necessary to have read “Brooklyn” to enjoy “Long Island,” but since the new novel revisits the scenes, characters and complications of the previous one, knowing the first makes reading the second that much more moving. In “Brooklyn,” after impulsively and secretly marrying Italian-American Tony, 18-year-old Eilis returns to Ireland after her sister's death and falls in love with a local bartender, Jim Farrell, only to have to return to Brooklyn, leaving to the bewildered. Jim, when a gossiper discovers her marriage.

Some 20 years later, the cuckold shows up on Eilis's doorstep, and in the meantime she has built what flashbacks suggest is a happy life, living with Tony and their two now-teenage children in an enclave on Long Island, near Tony's house. brothers and parents. After having made known to Tony her position on the dilemma (to choose the baby or her), Eilis returns home to Ireland to stay for a time with her 80-year-old mother, an intelligent, autonomous woman with ideas. defined and a clear resentment. against her daughter for leaving her alone all those years ago. In Enniscorthy, Eilis, of course, reunites with Jim, who has recently hooked up with her oldest friend, Nancy, widowed for five years.

What will Toni do? What about his family, who lives in other people's pockets? Will Eilis and Jim rekindle their romance? If so, what does that mean for Nancy? The tension of not knowing is intense, both for the reader and for the characters, who seem as unsure as we do about their next steps. The suspense is amplified by the way Tóibín deftly balances the story between the forces of secrecy and revelation. Eilis doesn't tell anyone, not even her mother, about her situation. Jim and Nancy don't tell anyone about their relationship. Eilis' mother and daughter remain silent about the pieces of the puzzle that have come into their hands.

Against all this retention, gossip (endless, omnipresent) acts tirelessly. Sometimes it's deliberate, even malicious, but mostly it's about all of Enniscorthy, like the Fiorello family on their Long Island cul-de-sac, living in a complicated, long-standing juxtaposition with the lives of others. They are all in the same story, in a sense that transcends the narrative of a novel. “Of course, everyone knows everything,” as he tells another one of Eilis' brothers. Even withholding gossip has a place in the plot. “I made the decision early not to be a gossip,” Eilis's mother tells her. “And it has always seemed that way to me.” Meanwhile, what she could have said could have changed everything.

The characters in “Long Island” constantly warn themselves not to say anything, for fear of disturbing that delicate balance that exists in both privacy and community. But not saying it is also an act that has consequences, something that Tóibín, a master of the art of it, exploits to exquisite effect at the end, leaving us wondering, once again, what's next.

Ellen Akins is a freelance editor and author of five works of fiction.