Book review

Letters

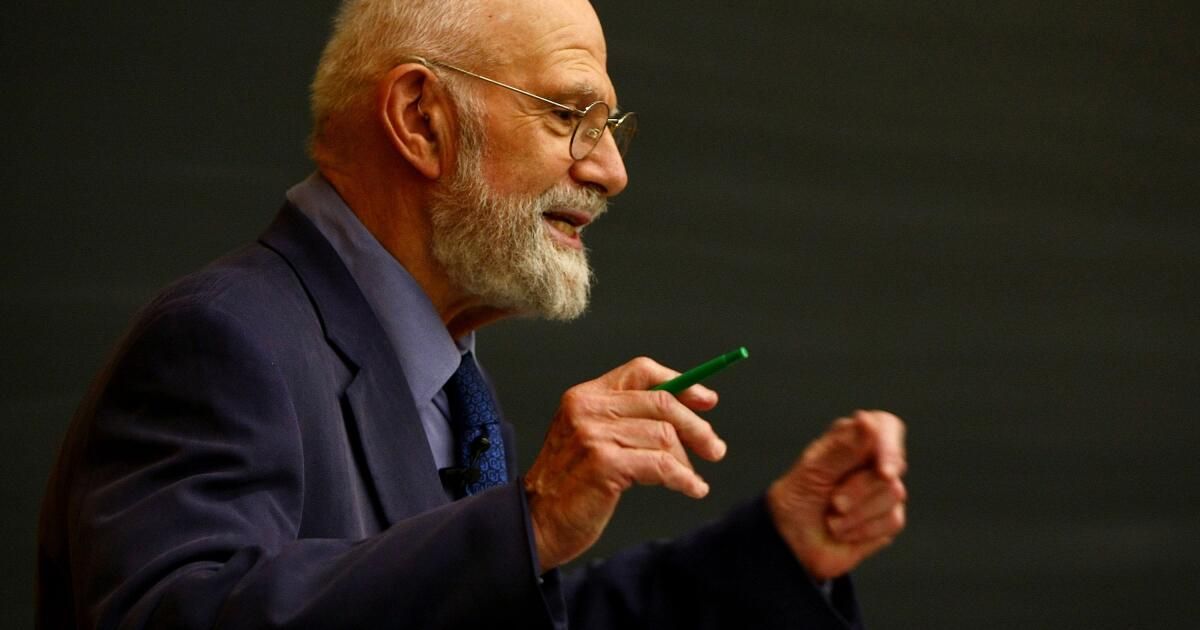

By Oliver Sacks

Knopf: 752 pages, $40

If you buy books linked to on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

There are those who know how to write and those who don't. No write. Oliver Sacks fell into the latter category. A neurologist by training, Sacks had an insatiable curiosity and wrote incessantly and happily about anything that caught his interest, which was almost everything. Readers will get a new glimpse into his mind this year, nearly a decade after his death, thanks to a compelling new collection of the doctor's letters compiled and annotated by his longtime editor, Kate Edgar.

To read these letters is to remember the deeply felt humanism and exuberance that Sacks brought to his prose: they include condolences, responses to fans, and long scientific reflections that read like essays in his books. There's not a hint of cynicism or pessimism here, just pleasure in sharing ideas and enthusiasm with friends, family, colleagues and fans. Sacks went to great lengths to respond to every letter he encountered, sometimes at great length.

The details of Sacks' life story were set out by the author in two autobiographies, “Uncle Tungsten” from 2001 and “On The Move” from 2015; the latter of which, as the letters reveal, was rushed to the terminally ill Sacks. melanoma, I could see it published. The letters can be read as an autobiography written in real time, as they portray the play of his mind as his life unfolded. They function as a kind of biography of Sacks's inner life and the happy and rigorous nature of his thought.

The son of two doctors, Sacks began life as if he were a young adult shot out of a cannon. Upon graduating from medical school in England, he bought a motorcycle and traveled across Canada and the United States, collecting adventures and friends along the way. After studying neurology at UCLA, Sacks landed in New York in the early 1960s, seeing patients at Beth Abraham Hospital and the Bronx Psychiatric Center before beginning his work in the headache unit at Albert Einstein. College in the Bronx.

The mind-body problem and the ways in which the diseased brain functions independently of human action became Sacks' lodestar, the topic that would preoccupy him for the rest of his career. He encounters some survivors of the encephalitis lethargica pandemic, who are living statues, unable to move or communicate, and had ideas on how to treat these patients.

As the letters reveal, Sacks's practical approach of spending considerable time with his patients and listening to those who could communicate, placed him on the margins of scientific thought. He writes to his parents that when his bosses question his methods, “there is a risk that someone with insignificant formal status like me will be crushed between two Leviathans.”

Unwavering, Sacks pressed on, and some of the extensive interviews he conducted with people suffering from severe headaches became the material for his first book, “Migraine.” The approach was a methodological apostasy among many headache researchers. He wrote to a British doctor who reviewed the book favorably: “A very eminent neurologist recently said to me: 'Your book is fascinating, but of course it is irrelevant.'”

Sacks's hybrid approach of combining field research and journalism techniques would make him the most famous neurologist in the world, although medical journals repeatedly refused to publish him. When in 1972 a London publisher offered to publish his book “Awakenings,” based on nine case studies of his patients with encephalitis lethargica, Sacks seemed enthusiastic but cautious. “Publishing such detailed information about living people can be distressing for them,” he writes.

“Awakenings” was published in 1973 and the book began Sacks’ career as a literary character in earnest. WH Auden called the book a masterpiece and a relationship was forged. “Thank you immensely for your magnanimous reaction to my book,” Sacks wrote to Auden in March 1973. “There are nobody whose favorable response could make me happier than yours.

Sacks continued his work as a doctor and author, one profession feeding the other. When he collected a series of essays he wrote about patients with unusual intellectual disabilities in “The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat,” Sacks entered a whole new realm of global recognition, which he found both satisfying and disconcerting. “There are certainly two sides to this business of… being known“I… passionately long for peace and quiet; I receive at least fifty or sixty letters and telephone calls a day.”

Superstar Sacks' letters at this time begin to be addressed to Susan Sontag, Deepak Chopra, Thom Gunn, Jane Goodall. The royalties from Sacks's publications had made him wealthy, and yet he doggedly pursued new avenues of interest, testing hypotheses in his letters about Tourette's syndrome and color perception with colleagues while producing essays and books with a fervor. almost graphomaniac.

Even as he contemplated his own impending death, Sacks moved forward quickly. “I am falling rapidly and I don't know how long I can expect to retain consciousness and coherence,” he wrote to editor Dan Frank in the summer of 2015, laying out his plans to “put together a modest (approximately 40,000 word) book” of essays. Even at the brink of death, Sack was alive to the world.

Marc Weingarten is the author of “Thirsty: William Mulholland, California Water, and the Real Chinatown.”