Recently, the founder of Nvidia, Jensen Huang, whose company builds the chips that feed the most advanced artificial intelligence systems today, task: “What is really, very surprising is the way in which programs an AI is like the way in which programs to a person.” Ilya Sutskever, co -founder of Openai and one of the main figures of the AI revolution, also fixed That is only a matter of time before AI can do everything that humans can do, because “the brain is a biological computer.”

I am a cognitive neuroscience researcher, and I think they are dangerously wrong.

The greatest threat is not that these metaphors confuse us about how AI works, but that they deceive us about our own brains. During the past technological revolutions, scientists, as well as popular culture, tended to explore the idea that the human brain could be understood as analogous to a new machine after another: a clock, a switchboard, a computer. The last wrong metaphor is that our brains are like AI systems.

I have seen this change in the last two years in conferences, courses and conversations in the field of neuroscience and beyond. Words such as “training”, “fine adjustment” and “optimization” are frequently used to describe human behavior. But we do not train, we refine or optimize the way it does. And such inaccurate metaphors can cause real damage.

The idea of seventeenth -century mind as a “blank” slate “imagined children as empty surfaces formed completely by external influences. This led to rigid educational systems that tried to eliminate differences in neurodivergente children, such as those with autism, ADHD or dyslexia, instead of offering personalized support. Similarly, the “black box” model of the early twentieth century of behavioral psychology claimed that only visible behavior mattered. As a result, mental medical care often focused on managing symptoms instead of understanding its emotional or biological causes.

And now there are new unpleasant approaches that arise as we begin to see the image of AI. Digital educational tools developed in recent years, for exampleAdjust the lessons and questions based on a child's answers, theoretically keeping the student at an optimal level of learning. This is strongly inspired by how an AI model is trained.

This adaptive approach can produce impressive results, but overlooks less measurable factors, such as motivation or passion. Imagine two children who learn piano with the help of an intelligent application that adjusts for their changing competence. One quickly learns to play without problems, but hates each practice session. The other makes constant mistakes but enjoys every minute. Judging only in the terms that we apply to the AI models, we would say that the child who plays without problems has overcome the other student.

But educating children is different from training an AI algorithm. That simplistic evaluation would not account for the misery of the first student or the enjoyment of the second child. Those factors matter; There is a good possibility that the child is fun is the one who still touches a decade from now on, and they could even end a better and more original musician because they enjoy the activity, mistakes and everything. I definitely believe that AI in learning is inevitable and potentially transformative for better, but if we evaluate children only in terms of what can be “trained” and “adjusted”, we will repeat the old error of emphasizing production on experience.

I see that this develops with undergraduate students, who, for the first time, believe that they can achieve the best results measured by completely outsourcing the learning process. Many have been using AI tools in the last two years (some courses allow it and others not) and now they trust them to maximize efficiency, often at the expense of genuine reflection and understanding. They use AI as a tool that helps them produce good essays, however, the process in many cases no longer has much connection with the original thought or discover what causes the curiosity of the students.

If we continue to think about this brain framework such as AI, we also run the risk of losing vital thinking processes that have led to great advances in science and art. These achievements do not come from identifying family patterns, but of breaking them through disorder and unexpected mistakes. Alexander Fleming discovered penicillin by noticing that the mold that grew on a Petri plate that had accidentally left out was killing the surrounding bacteria. A lucky mistake committed by a messy researcher who went to save the lives of hundreds of millions of people.

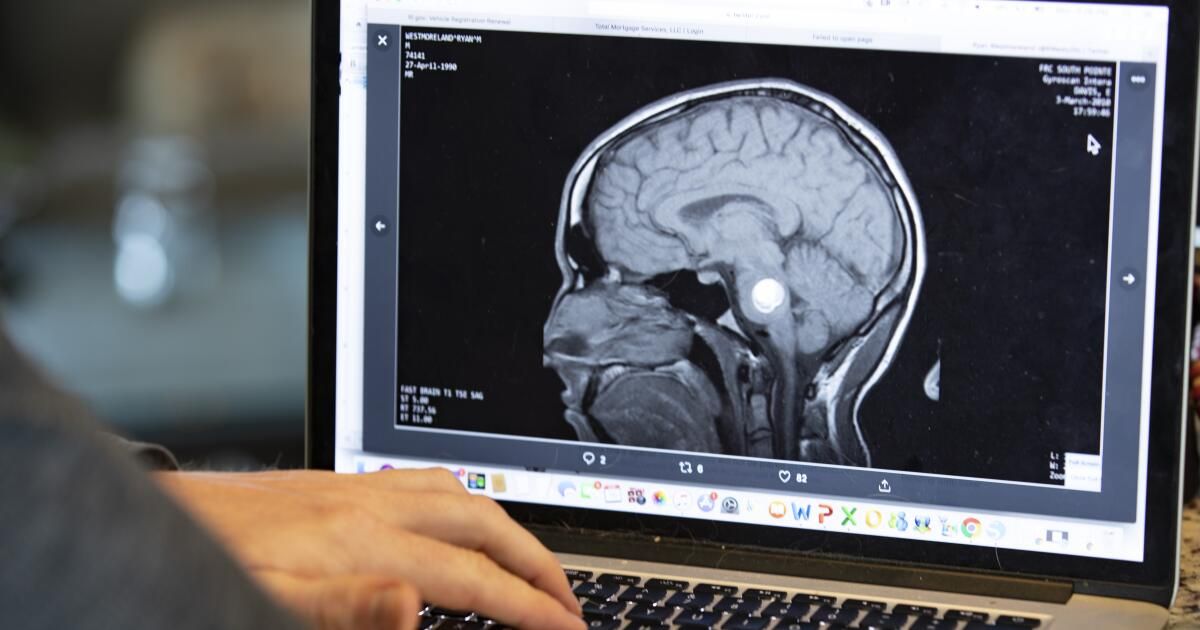

This disorder is not only important for eccentric scientists. It is important for each human brain. One of the most interesting discoveries in neuroscience in the last two decades is the “network of default”, a group of brain regions that is activated when we are dreaming dreaming and we do not focus on a specific task. It has also been found that this network plays a role in reflection on the past, imagining and thinking about ourselves and others. Not taking into account this mental weight behavior as a failure instead of adopting it as a central human characteristic inevitably leads us to build defective systems in education, mental health and law.

Unfortunately, it is particularly easy to confuse AI with human thought. Microsoft describes generative AI models such as chatgpt in its Official website as tools that “reflect human expression, redefining our relationship with technology.” And the Operai CEO, Sam Altman, recently highlighted his new favorite feature in Chatgpt called “Memory”. This function allows the system to retain and recover personal data in conversations. For example, if you ask ChatgPT where to eat, I could remind him of a Thai restaurant who mentioned wanting to try months before. “It's not that you connect your brain in one day,” Altman explained“But … I would know you, and it will become this extension of yourself.”

The suggestion that AI's “memory” will be its own extension is again a defective metaphor, which leads us to misunderstand the new technology and our own minds. Unlike human memory, which evolved to forget, update and remodel memories based on innumerable factors, the memory of AI can be designed to store information with much less distortion or oblivion. A life in which people outsource memory of a system that remembers that almost everything is not an extension of the self; It breaks the same mechanisms that make us human. It would mark a change in how we behave, we understand the world and make decisions. This could start with small things, such as choosing a restaurant, but you can quickly advance much larger decisions, such as taking a different professional career or choosing a different partner than we would have, because AI models can superficial connections and the context that our brains may have cleared for one reason or another.

This subcontracting can be tempting because this technology seems human for us, but AI learns, understands and sees the world in fundamentally different ways, and really does not experience pain, love or curiosity like us. The consequences of this ongoing confusion could be disastrous, not because AI is inherently harmful, but because instead of shaping a tool that complements our human minds, we will allow us to remode it to its own image.

Iddo Gefen is a pHD candidate in cognitive neuroscience at Columbia University and author of the novel “The cloud factory of Mrs. Lilienblum. “. Your subtrovation bulletin, Neuron storiesConnect neuroscience ideas with human behavior.