My grandmother escaped from the Warsaw Gueto after her first of the four sisters died of hunger. He slid through some missing bricks in the wall that sealed the Jewish population of their Aryan neighbors, where they were caught in poverty and malnutrition and subject to Nazis extermination plans. Academics report that 92,000 Jews died of starvation in the ghetto before 300,000 were deported to camps. After escaping, my grandmother, just a teenager, cast the food to her family several times before the rest of her family died, and my grandmother remained hungry for many years, while surviving the Holocaust on her own.

“When you are hungry, Alma flies,” Bubbe said, as I called her, in His survival testimony. Bubbe is more tragically poetic in his hunger descriptions, and never forgot the way his sister died asking for a piece of bread, just one Broyt fun shieldle. Bulky eyes and blue lips. My grandmother's relationship with food was marked forever by the ghost of hunger. Once he lived safely in the American suburbs, he was never without a rye bread bar in the freezer.

My grandmother knew about the essential dignity of each human being. At the end of the war, when the Russians freed her in the Polish city of Lukov, she noticed the German soldiers walking without boots, and felt sad for them. “You see that a person is injured,” he said, “you want to help.” How we respond to the needs of those around us: this is what forms the basis of our character.

When drawing a book about the history of my grandmother, I often thought about the “hierarchy of needs” of the psychologist Abraham Maslow. In the lower part of the pyramid is our basic physiology, our need for food and water, and above that our need for safety and safety. Only when these needs are met, we can focus on upper planes, seeking belonging, self -esteem and self -realization. It is only because my grandparents fought so much, they endured so much, because of their bread that I am in a position to reflect on what my grandmother's struggle means for survival for my identity, my sense of meaning and my policy.

His legacy taught me that each group of people deserves to live free of hunger and fear of violence in their homes, that we all need bread and boots. She taught me that we should tell stories, all stories, exile, loss and persecution. She taught me to love and believe in the United States, and that the Jews of the world are safer in liberal democracies, with governments that grant equal opportunities for all in their jurisdiction.

As I learned more about Jewish history, I came to believe that the long history of Jewish suffering resulted in an attempt to solve “the Jewish problem” creating a Palestinian problem, that the Israeli government has never considered sufficient with its role in the Palestinian persecution, and that the fate of the Palestinians and the Israelis are, consequent For the future.

I can imagine this future more easily because I, unlike my grandmother, unlike my Jewish cousins in Israel, already a difference from all Palestinians who live under occupation, I have not feared for basic survival. But those who have lost more than I have Share this vision. And I think it's my duty, at least, clinging to my imagination.

But before hunger, words and ideas begin to melt, then evaporate. Hunger is stupifier.

Gaza growing star statistics change daily, and they are all bad. In May, 5,000 children diagnosed with malnutrition. A 24 -hour period with 19 deaths from hunger. At least 1,400 people have been killed in Gaza While trying to access food from the Humanitarian Foundation of Gaza, an American and Israeli organization with opaque funds that 25 experts have called a “Insulate the company and humanitarian standards” He began to dominate the distribution of aid in the Gaza Strip, in the name of diverting Hamas' food. The blockade, the system of severe restrictions in the movement of goods and people inside and outside Gaza, has stopped the flow of food and medical supplies, and frequent Telecommunications breakdown They have severely challenged efforts to distribute what the help enters.

Outside of Gaza, we are able to discuss statistics and discuss what words we use to describe the suffering of other people. Many academics have called for constant murders, the reduction of the Palestinian infrastructure to debris and the systematic blockade of humanitarian aid A genocide. For many Jews with direct connections with the Holocaust, the history of genocide is so total, so unimaginable, it is difficult to reconcile a word with such a totemic power with something that happens at this time, in front of our eyes, on our phones.

However, some Jewish holocaust survivors Identify with the images of the destruction of Gaza and feel forced to use the strongest language available in the conviction. Others use ethnic cleaning terms, or crimes against humanity, while some just want to call this a war. These distinctions are important; A designation of genocide, theoretically, would force the international community to act, with penalties or criminal prosecution for those responsible. But this semantic dialogue can produce a kind of despair in white. Hungry children make fine distinctions feel hollow.

The Israeli government states that there is “There is no hunger” In Gaza, even when officials have moved to address this hunger in response to international and internal pressure, with PAUSE A MINIMUM LINK AND AIR DROPS. The defenders of Israel admit that there is a problem of starvation in Gaza, but they blame Hamas and Hamas infiltrated to international organizations for looting humanitarian aid, an affirmation that has been widely discredited.

The Israeli government says that this is a war of defense. This is the logic that has led, for example, to Siege of the already limited clean water of Gaza supply. We can recognize violence, constant fear and the deep disappointment that both peoples have experienced for decades, without equating these experiences, while seeing clearly the moral imperative: food and water for all must come before security for some, all of which must come before ideology. This formulation implies that those who wield most resources, Israeli and American institutions must be willing to sacrifice some security in the name of ensuring that familiar people are fed. There is no future for Israelis or Palestinians in which the safety of people is presented before the basic physiological needs of other people, in times of war or later.

All of us attending to today's news we are narrowing our eyes through intergenerational memories. I looked at photos of the hungry gazans and returned to the Polish ghetto where I never lived, seeing a family member to die. I have seen the Jews that I love to walk freely through the streets of American cities and perceive the threat in the symbols of Palestinian liberation that they do not understand. I have heard panic of known Jews about how strong the sirens in the protests in front of the Israeli embassies. For them, perhaps the sirens feel like war airplanes.

What happens with those of us who live at the top of the Maslow hierarchy is that sometimes we fall into lagoons and touch the panic of basic survival, bringing our identities and our policy, with us. We can have compassion for each other right now. But we must anchor these facts: at this point, in Gaza, some people are not eating. That is why so many worldwide are crying and risking your safety and your status to protest. Our intergenerational pain should lead us all to cry together, in the name of the most vulnerable.

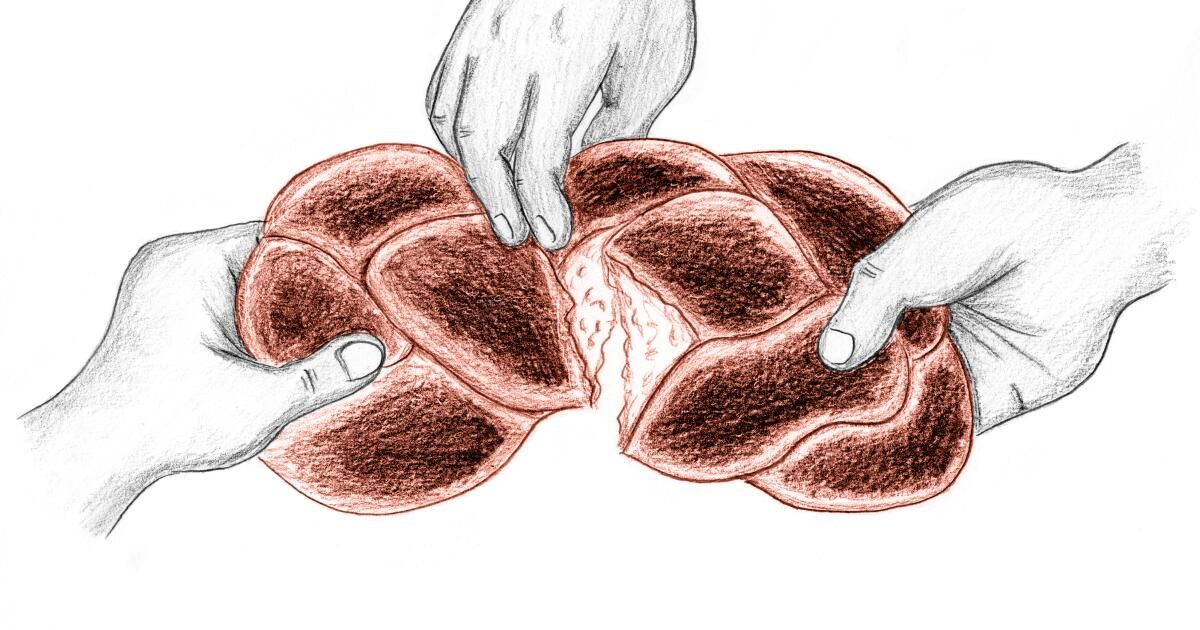

Artists and activists have no perfect plans to resolve the most complex political crises of our lives, and we do not command armies or handle many resources. What we can do is cry. We can cry for what is deeply bad with now, and we can use our imagination to turn on the way to follow. Where our imagination is fixed could guide our collective priorities. So I imagine the children of Palestine in my drawings. They are breaking bread with my grandmother's sisters, even if only in my imagination.

Amy Kurzweil He is a New York cartoonist and author of “Artificial: A love story” and “Flying Couch: A graphic memory. ”