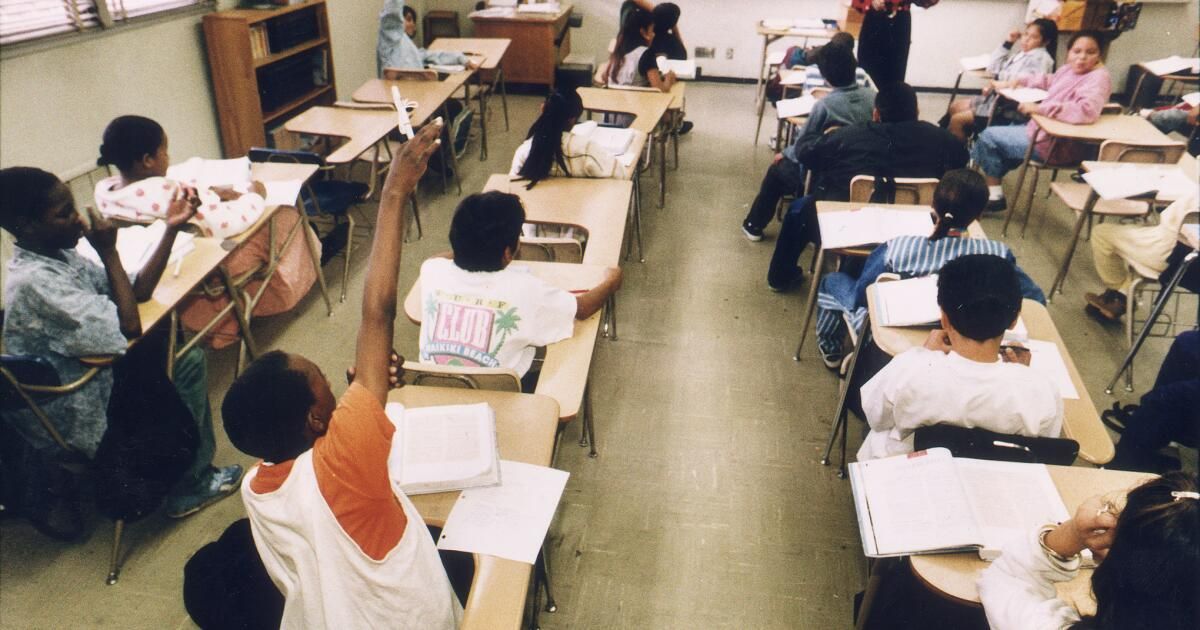

In general, schools have been working hard to meet the special educational needs of a variety of students: those with learning disabilities, those learning English, those with behavioral problems, and those whose households struggle with poverty. But they have largely neglected an important group of students with special needs: the academically gifted.

Many school districts across the country have abandoned programs for quickly adapting students. The trend to eliminate or reduce such programs began about 15 years ago. But it gained traction in 2021, when the Black Lives Matter movement caused schools to reckon with the disconcerting fact that they were much less likely to identify Black and Latino students as gifted than white and Asian students.

Part of the problem was that the original purpose of gifted programs had been lost in parental competition for prestige and perks. Unlike other special education categories, parents coveted the gifted label. Classes and sometimes entire schools for gifted students often had more complete curricula and more resources. They became classrooms for high-achieving students rather than students properly defined as gifted.

Originally, these programs were intended to meet the needs of students with intense and often irregular learning patterns. It used to be considered that they did not need special attention because they often stuck out. Because standardized testing required schools to target students' proficiency, all attention was focused on those who had not met that mark. Those who passed it were considered good.

But they are not only good. Gifted children, more than others, tend to shine in certain aspects and struggle in others, a phenomenon known as asynchronous development. A third grader's reading skills may be at the level of an 11th grader, while his or her social skills are more like those of a kindergartener. They often find it difficult to connect with other children. They are also in danger of being rejected by the school because the lessons move slowly.

I don't know if I would have been identified as gifted as a child, but I was certainly bored to death in elementary school. It felt like everything was repeating itself to the point where paying attention in class wasn't worth it. I started acting out just to keep myself busy.

My third grade teacher tried a few strategies, including sending me on made-up errands just to get me out of the classroom. Nothing worked. So I was sent to fourth grade even though school policy prohibited it.

That was a disaster. I was isolated from my friends and anxious about the constant questioning from adults and children who asked me why I was in the upper grade. Academically it didn't work either. I enjoyed the challenge of catching up, but once that happened, school became boring again. The problem wasn't the third-grade material; It was the pace of learning.

When I started covering education in the late 1970s, it was a pleasant surprise to see this need being addressed, although it was a little disheartening to hear a 10-year-old girl describe herself as a “mentally gifted minor” in a school. . board of directors meeting. “MGM” was the name given to the programs, which were later renamed “GATE,” for Gifted and Talented Education.

However, it was never clear exactly what gifted education was. In some districts, there were highly sought-after schools dedicated to high-achieving students. Sometimes it was an enrichment for certain students. Teachers were supposed to have special training, like any special education teacher would, but it seemed unpredictable. In the schools my children attended, the gifted program basically meant extra homework.

When giftedness became a matter of prestige rather than a particular learning style and need, all bets were off. Maybe the problem was calling it “gifted” instead of “asynchronous development”; No one is going to fight to get their child into an asynchronous developmental program unless they need it.

There is no doubt that racism played a role in the identification of children as gifted, even though the label was based on supposedly objective criteria. But the solution to that problem is to eliminate bias, not the programs themselves.

To its credit, the Los Angeles Unified School District has preserved gifted education, with programs that address different academic and creative abilities. One is for very talented students, who may have a good grasp of college material in some areas while still a sophomore in high school. But the under-enrollment ratio of students of color led the district to relax its entrance requirements before recently reversing course. The criteria should be fairly simple: whether a student needs and can move extremely quickly through the academic material.

California does not require schools to offer gifted programs and stopped funding them in 2013, so schools have little incentive to maintain them. The answer is certainly not to remove the programs completely. Opening them to all children does not seem to have helped either; That led some to slow down, defeating their purpose.

Differentiated instruction (in which a teacher adapts lessons to different students' needs) sounds good, but it is difficult to implement in a large class.

My oldest daughter was lucky enough to be in a small program within her public school, open to all until spots were filled, which solved much of the differentiation problem. It involves few tests and many individual projects. Students chose their own books to read and report. Their projects could be written reports or, if their talents lie elsewhere, films, plays, songs or board games, as long as they demonstrate that they have learned the lesson in question. It gave students free rein to work at their own level, avoid boredom, and showcase their talents.

But that program was run by two extremely talented teachers who knew how to bring out the best in each student. It is much easier to grade a test than to evaluate a project, and I don't know to what extent the program could be replicated. In any case, it no longer exists.