Book Review

Compton in my soul: a life in pursuit of racial equality

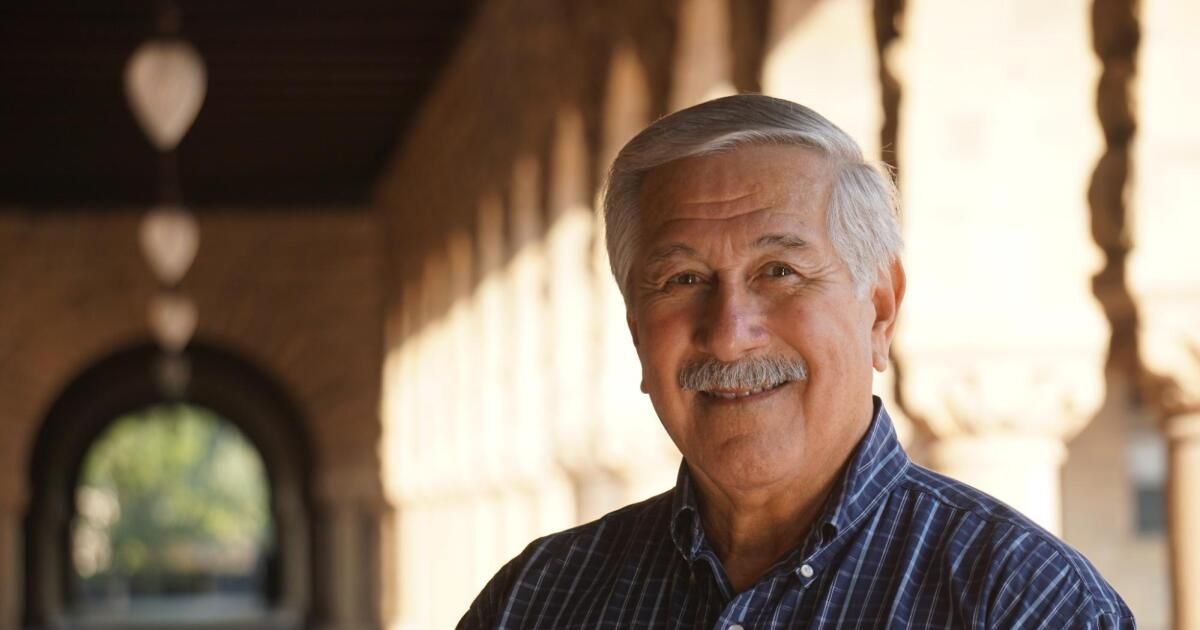

By Albert M. Camarillo

Stanford: 312 pages, $28

If you purchase books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

After learning firsthand about racial injustice in his hometown of Compton, where he was born in 1948, Albert M. Camarillo spent more than four decades fighting for racial equality as a history professor at Stanford University. His new memoir moves back and forth between his story and Compton’s, illuminating both.

Camarillo recounts Compton’s story in the decades after World War II, when he became increasingly black and deprived, and traces his remarkable academic career as one of the founders and shapers of the field of Chicano history, which began in its infancy in 1975 when he graduated as the first Mexican-American to earn a PhD in U.S. history with this specialization. Camarillo, ever the historian, also frequently inserts episodes of Chicano and American history alongside the story of his own life, which he relates in his own unflappable way.

The result is a drama-free blend of memoir and historical study aimed at multiple audiences. Throughout, Camarillo makes clear that his Chicano identity is intertwined with his scholarly agenda: to expand the standard narrative of American history to include people like himself.

The Compton in Camarillo's soul predates the city that became notorious in the 1980s for gang violence. The first part of the book traces Compton's history from the 1910s, when his father and mother's families first arrived, to Camarillo's decision in 1966 to attend UCLA, 20 miles and a world away. . He grew up “Chicano style”, that is, dark, poor and subject to what he calls “Jaime Crow”. As a young man, he also witnessed Compton's sudden transformation from a majority white city to a black city, a dramatic demographic shift that soon triggered, as in other parts of the country, white antagonism and flight, and the eventual destruction of the tax base. . Camarillo details family precursors to urban decline as he shares his generally positive memories of Compton during the 1950s and 1960s. Attending public schools, he enjoyed black, white, and Latino friends. Camarillo, elected to leadership by his high school teachers, led his high school's effort to cultivate multicultural understanding in the wake of the Watts riots of 1965. The complex landscape of post-World War II Los Angeles informed his commitment to diversity once he became a teacher. .

Because the K-12 education he received only minimally prepared him for college, the second part of the book explains how a young man who finished his first year at UCLA on academic probation became a full professor at one of the best universities in the world. universities in the country. The key here was discovering his love of history along with a political awakening inspired by the protest politics of the time, including the anti-Vietnam War movement, the civil rights movement, and, most importantly, the Chicano movement.

Camarillo felt a sense of “genuine freedom” in publicly declaring himself Chicano, which in the 1960s emerged as a politicized ethnic identity that activists used to signal their dedication to improving the lives of all Mexican Americans. This commitment was reflected in Camarillo’s research and shaped his career. At a time when few scholars studied Mexican Americans and those who did largely characterized them as a problem, the idea that their lives and stories were not only significant but even integral to American history was revolutionary. Even before he finished his dissertation, Stanford University came knocking with a job offer.

That dissertation became the 1979 book “Chicanos in a Changing Society: From Mexican Pueblos to American Barrios in Santa Barbara and Southern California, 1848-1930,” which remains a classic text within the field of Chicano history for demonstrating the lasting repercussions of the Mexican-American War for the thousands of Mexican citizens who in 1848 suddenly found themselves living in the American Southwest.

In addition to earning tenure, the book also secured Camarillo’s platform to fight for racial equality in academia. Highlights of his distinguished career mentioned in the book include his contribution to the founding of a center for comparative research on race and ethnicity at Stanford and the fostering of intercollegiate research beyond the campus. Among his most enduring legacies, Camarillo mentored a number of graduate students who have, in turn, mentored many more. Most recently, Camarillo testified before state lawmakers in support of California’s 2021 law mandating the inclusion of ethnic studies in California’s high school curriculum beginning in 2026.

Although these events are far removed from Compton, in the final part of the book, Camarillo “returns to his roots,” inspired to counter sensational reports about the city with stories of resilience and hope. Interested in the city's history since graduate school, Camarillo shares some of the research he has conducted in the years since, including oral history interviews with long-time residents. He also details how supporting public education in the city became a family affair after his eldest son became a public school teacher in Compton.

The book is thus a hybrid narrative, with specific parts likely to appeal to different audiences. The administrative and teaching triumphs are probably of most interest to fellow academics, while the information it conveys about Compton is likely to appeal to Angelenos and Los Angeles history buffs. As for the young people it mentions who might read the narrative someday, they are a group likely to benefit from its brief historical synopses that provide context for the events of their lives.

The book is infused with Camarillo's calm, confident, and determined attitude, the same attitude that once earned him a walk-on spot on UCLA's freshman basketball team and that undoubtedly contributed to his remarkable educational career. . Neither the upheavals he and his hometown experienced nor the challenges he faced as a young academic are sources of much dramatic tension. Instead, Camarillo focuses on the positive, the importance of family and community, the benefits of multiculturalism for advancing research and building a more just nation, and the power of perseverance. Significantly, Camarillo acknowledges his wife, Susan, as a constant source of support, while also taking comfort in knowing that, as he put it, “true social and institutional change is a multigenerational project.” In keeping with that sentiment, he ends his story with the hope that the book can inspire future generations of change-makers.

We need not wait. Camarillo’s powerful life, his decades of agenda-setting scholarship, and his extraordinary dedication to teaching all reflect an academic career committed to political activism but imbued with gentleness and generosity. In an era of political polarization and a careless disregard for evidence among some partisans, his book offers a refreshing antidote and a useful model.

Lorena Oropeza, a professor of ethnic studies at UC Berkeley, is the author, most recently, of “The Adobe King: Reies López Tijerina, Lost Prophet of the Chicano Movement.”