Book review

The Plot Against Native Americans: The Fateful History of Native American Boarding Schools and the Theft of Tribal Lands

By Bill Vaughn

Pegasus Books, 256 pages, $29.95

If you buy books linked to on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

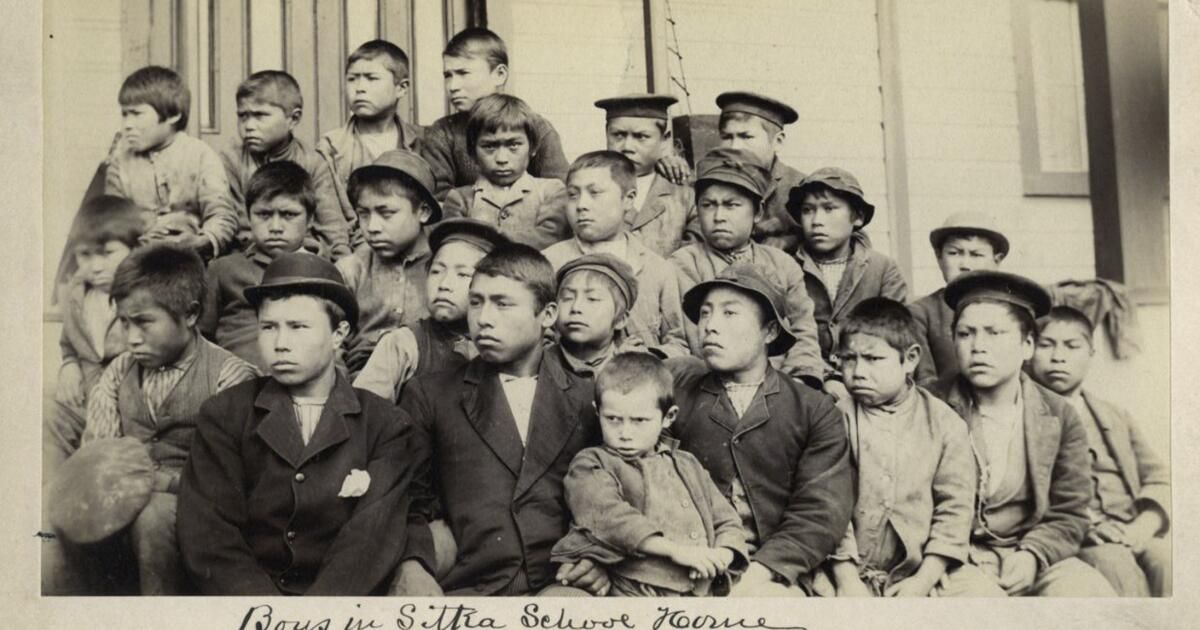

In November 2000, the Heard Museum in Phoenix opened a groundbreaking exhibition, “Remembering Our Indian School Days: The Boarding School Experience.” The show, so popular that an updated version remains on viewshowcased the voices of Native American children sent to federally run boarding schools designed to eradicate their cultural heritage and assimilate them into white society.

Uprooted from their communities, they were subjected to miserable living conditions, military-style regimentation, religious conversion, forced labor, and traumatizing physical and sexual abuse. Students were harshly punished simply for speaking their own language. Some fled. Many died of disease and their bodies were often not returned to their families.

Bill Vaughn, author of “The Plot Against the Native Americans.”

(Kitty Herin)

The repercussions of this 19th and 20th century tragedy are still being felt in both the United States and Canada. Apologies and investigative reports have proliferated. Trials for reparations and battles for the exhumation of school mass graves continue.

Bill Vaughn’s “The Plot Against the Native Americans,” which plays on a title by Philip Roth, is billed as “the first narrative history to reveal the full history” of these boarding schools. That would make it an important book, if only its narrative weren't such a strange, disjointed mess.

Vaughn is on the right side of history. And although he is not Native American, he has a personal interest in the events he recounts. His great-grandfather worked as a caretaker at St. Peter's Mission, a boarding school in Montana, and his grandfather and mother were born there. But no matter how well-intentioned, his book desperately needed an editor to nudge its anecdotes and digressions toward coherence.

To a surprising extent, Vaughn jumps through time and space, bouncing through centuries and wandering to places as far away as Paraguay. Perhaps he was drawing, however clumsily, from the nonlinear worldviews of Native American cultures, many of which view time as circular. Most likely he was simply free associating.

Cover “The Plot Against the Native Americans”

(Pegasus Books)

Another problem, perhaps the central one, is that Vaughn does not seem clear about the boundaries of his subject. A better book might have focused more closely on the boarding school saga, including its context and legacy. Vaughn weaves together stories of some boarding school children, including Nancy Bird, a multilingual Métis (mixed-race) girl from Montana's Blackfeet Indian Reservation and a student at St. Peter's and the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania. Elsewhere, he offers harrowing accounts of physical and sexual abuse.

Too often, however, Vaughn digresses into the broader tragedy of American colonization, with its consequences of war, disease, and land theft, as well as the cultural destruction embodied by boarding schools.

It refers to the modern activism of the American Indian Movement, including the occupations of Wounded Knee and Alcatraz; the Dakota Access Pipeline protests; the resurgence of endangered Native American languages and successful efforts to expose massive corruption at the U.S. Bureau of Indian Affairs. One of his heroes is MacArthur Foundation Fellow Elouise Pepion Cobell, a member of the Blackfeet Nation who trained her accountant's eye on the bureau's mismanagement of Native American trust funds.

But at best, Vaughn can only offer a scattered portrait of the dangers and consequences of colonization, stories already told elsewhere. His inability to resist a colorful anecdote, no matter how tangential, is evident in his analysis of General George Armstrong Custer and the Battle of Little Bighorn. Vaughn details the mutilation of Custer's corpse after the battle, with sewing awls and an arrow, in ways too gruesome to repeat here. He dismisses Christopher Columbus, once hailed as the discoverer of America, as “this murderous slave trader.”

A key point Vaughn makes is that not all Indian boarding schools were created equal. It makes a distinction between Catholic boarding schools, operated by Jesuits, Franciscans, Ursulines and other orders, and schools directly under the supervision of the U.S. government. The latter were often run by Protestant evangelicals, who also had their own boarding schools.

The Catholic Church, Vaughn suggests, was more interested in religious conversion than in other aspects of assimilation. As a result, their schools, at least initially, were more tolerant of native languages and customs. For this reason, some tribal parents, eager for their children to receive an education, enrolled them voluntarily.

After a while, the distinctions blurred. Catholic schools, including St. Peter's, also imposed appalling living conditions and strict rules, and were often beset by abuse. One of Vaughn's many villains is Katharine Drexel, a wealthy Philadelphia nun whose fortune helped support Catholic boarding schools after the federal government, in the late 19th century, began phasing out their financial support.

Another important figure is Richard Henry Pratt, who ran Carlisle, the first and perhaps best-known of the federal boarding schools. Pratt was both a fervent evangelical Protestant and an assimilationist, and Carlisle, founded in 1879 and closed in 1918, was a grim place. But although his methods were brutal and reckless, you could tell that Pratt did care about his defendants. He wanted, he said, to “elevate the Indian race” and opposed both the segregation of blacks in the army and of Indians on reservations.

Given Vaughn's personal connection to the boarding school's history, “The Plot Against the Native Americans” can be interpreted as his modest attempt to obtain reparations. But, like so many similar efforts, it falls dramatically short.

Julia M. Klein is a reporter and cultural critic in Philadelphia.