book review

Blood test: a comedy

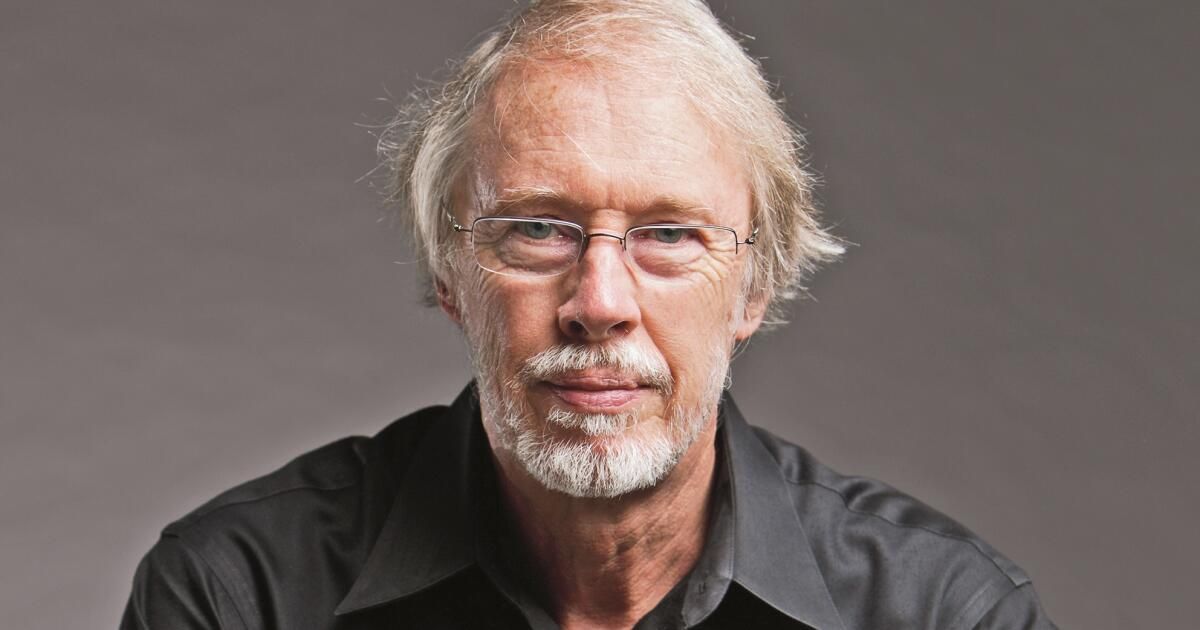

By Charles Baxter

Pantheon: 224 pages, $28

If you buy books linked to on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

“If you fall here in Kingsboro, Ohio, you're in good company,” says Brock, the narrator of Charles Baxter's new novel, “Blood Test.” It's true that a lot goes wrong for Brock and those around him in this fictional town. His ex-wife's new boyfriend is a jerk who spouts doctrines from a group distressingly similar to Scientology. Your teenage son appears to be planning to harm himself. Your teenage daughter has become too comfortable with her boyfriend. Who wouldn't want a little certainty in the face of all this?

The “Blood Test” setup is a careful answer to that question. During a doctor's visit, a company called Generomics Associates invites Brock to take a blood test that “predicts behavior and tells you what you're going to do before you do it.” Thanks to advanced medical technology and artificial intelligence, we can now perform predictive miracles for society. Excellent! Less good: The test informs Brock that he will almost certainly commit a heinous crime.

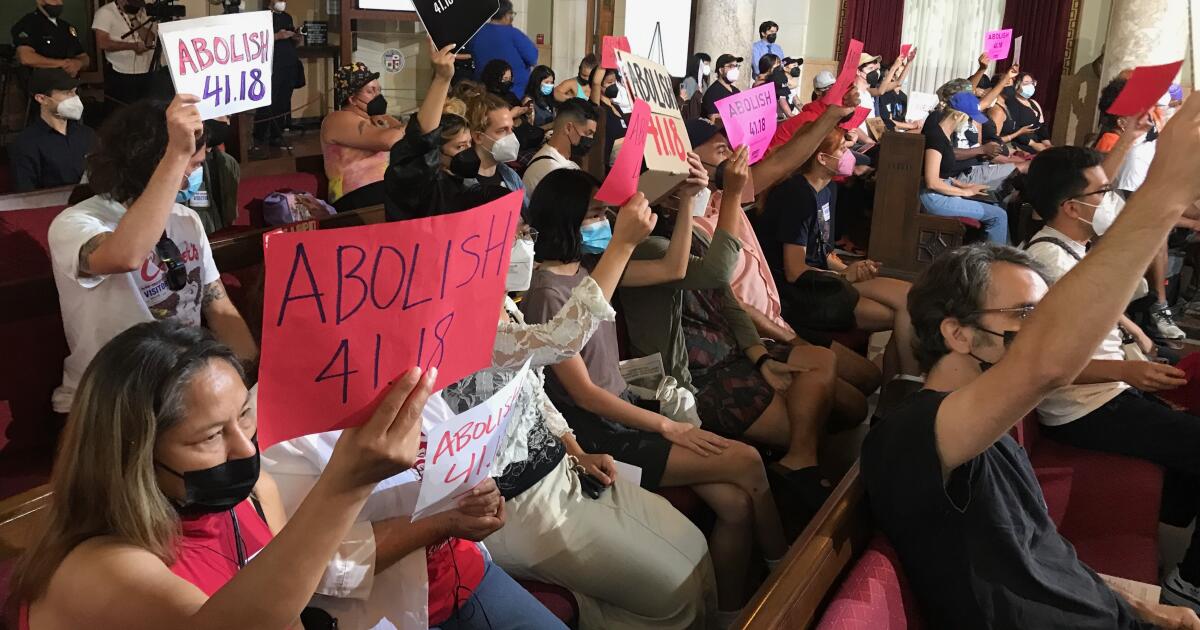

Many critiques of contemporary American life arise from this simple, almost folkloric setting. You're up against fraudulent pseudoscience (think Theranos and its own false promises about blood testing). Gun culture. Legal nonsense. Church culture. Protestant predestination. Cults. Manifest Destiny. The algorithm. Masculinity.

Baxter, a veteran storyteller who has been nominated for a National Book Award and has written and edited several books on the craft of fiction, has a gift for giving each of these social stressors their due while keeping the story going. in motion. The novel is subtitled “A Comedy,” but he has written something closer to a farce: a story in which every situation is intentionally absurd. (“If you don't like crazy stuff, you probably shouldn't live in America,” Brock notes.) And it still looks a lot like reality.

Brock, a humble and serious insurance salesman and Sunday school teacher whom his son calls “Mr. Reliable”: begins to flirt with petty theft. Maybe a little shoplifting will prevent more serious transgressions? No: Upon learning that his ex-wife Burt's new partner has been using homophobic slurs toward his son, Brock insists on a confrontation. There are words. Cue the banana peel. Suddenly, Burt suffers a debilitating skull fracture.

Whether this constitutes an accident, a violent attack, or some kind of self-fulfilling prophecy, forces beyond Brock's control are instantly set in motion. Generomics, who learns of Burt's fate, arrives with new information for Brock, the promise of an insurance policy, and the delivery of an unwanted weapon. Brock’s girlfriend watches Generomics and sees an existential nightmare: “They gave you permission to do anything. Everything is allowed once they say so.”

However, Brock is a little more restrained. He thinks about his high school friends for whom “guilt rolled off…like rainwater off a goose.” Why not him too? The Internet says he's destined to be evil, and lawyers say even if he is, he'll be spared jail time. Perhaps having a conscience is overrated in this brave new world.

That's the biggest, juiciest goal of “Blood Test”: an America whose citizens are encouraged not to think, or only to think selfishly; where we should expect to get our way, with the help of technology. It's an idea a novelist can only explore in comedy to avoid seeming like a scold.

And “Blood Test” is a fun, if careful, book. Sometimes Baxter opts for a throwaway joke (“Women don't like it when you make generalizations about them”) or a quirky scene (watch a B movie in which a robot somehow becomes the Pope). But above all, Baxter is a deadpan artist: he has made Brock as blandly Midwestern as possible to further highlight the savagery of contemporary American life.

In that sense, “Blood Test” is a kind of heir to Don DeLillo’s classic “White Noise,” another story about a Midwestern family fractured by technology and the growing sense that we are no longer in control of our own destinies. . . Like DeLillo, Baxter feels driven to satirize the ways in which every atom of our consciousness seems to be for sale. (“We have ways to monetize dreams, if you're interested,” a Generomics doctor tells Brock. “These are bargain dreams. We could bring you downstairs, for pennies on the dollar.”) But Baxter has eliminated some. of the coldness of DeLillo's prose, allowing Brock to be a warmer postmodern patriarch.

It's not too revealing to say that “Blood Test” ends with a duel: there are few better ways to symbolize American us-versus-them culture. It is also, in an era of regular mass shootings, an almost quaint and comical way to frame a battle of wills. “Ours is a violent country where a single bullet rarely matters,” as Brock says. That's not an obvious laugh line. But after Baxter has introduced the parade of selfish, money-hungry, blindly technology-admiring elements of contemporary life, the black comedy of words shines.

Mark Athitakis is a Phoenix writer and author of “The New Midwest.”