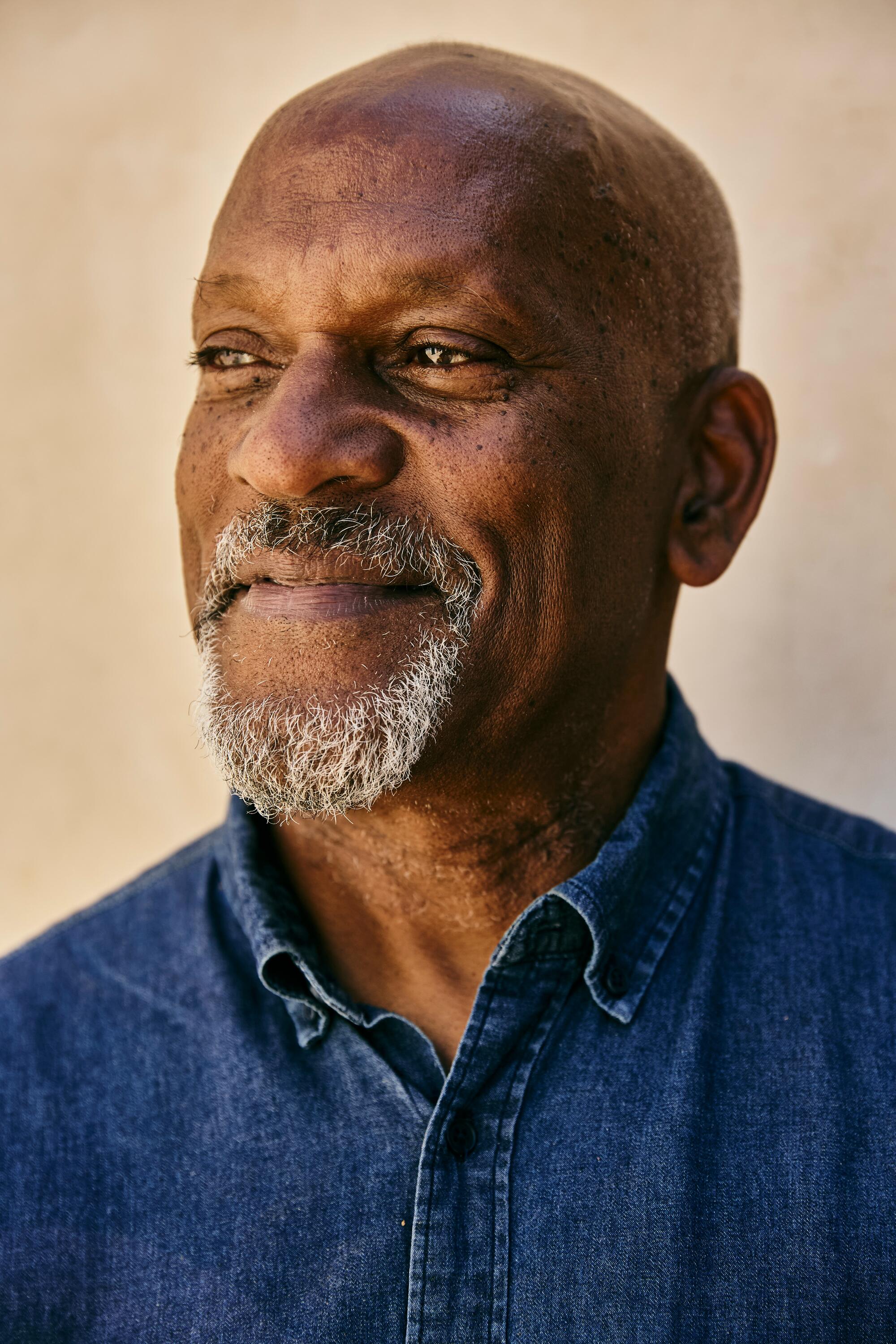

On a hot August morning, the sunlight is found through a teak dining table of warm tones in the backyard of Harold Greene in San Pedro. The table, which Greene built, has a long bank on one side and two handmade chairs in the other, all resting on a wooden cover that she also built.

In this series, we highlight independent manufacturers and artists, from glass outbreaks to fiber artists, which are creating original products in Los Angeles and their surroundings.

Near its exclusive Soliarc Chaise Lounge enjoy the sun. Beyond a flourishing gold medallion tree, and at the end of a space of spaced concrete tiles, there is a shed with a marine green door that houses the heart of the work of his life. Within the carpentry study of 250 square feet is where Greene has spent more than four decades shaping her legacy.

From personal pergolas and dining tables to commissioned banks, even a bridge for the rest gardens, Greene has built a life in custom -made custom furniture.

“It's like this obsession: finding a piece of wood and doing something with it,” Greene said, sitting in the small studio of tools with guitars in progress hanging next to sun hats and wooden slabs. “Each piece of wood has a life.”

Harbor City's native has made furniture since the 1970s, but his first elaboration memories date back to childhood. Higía rummage in search of wooden remains behind a neighborhood factory with his brother and make toy cars and cane arches that collected.

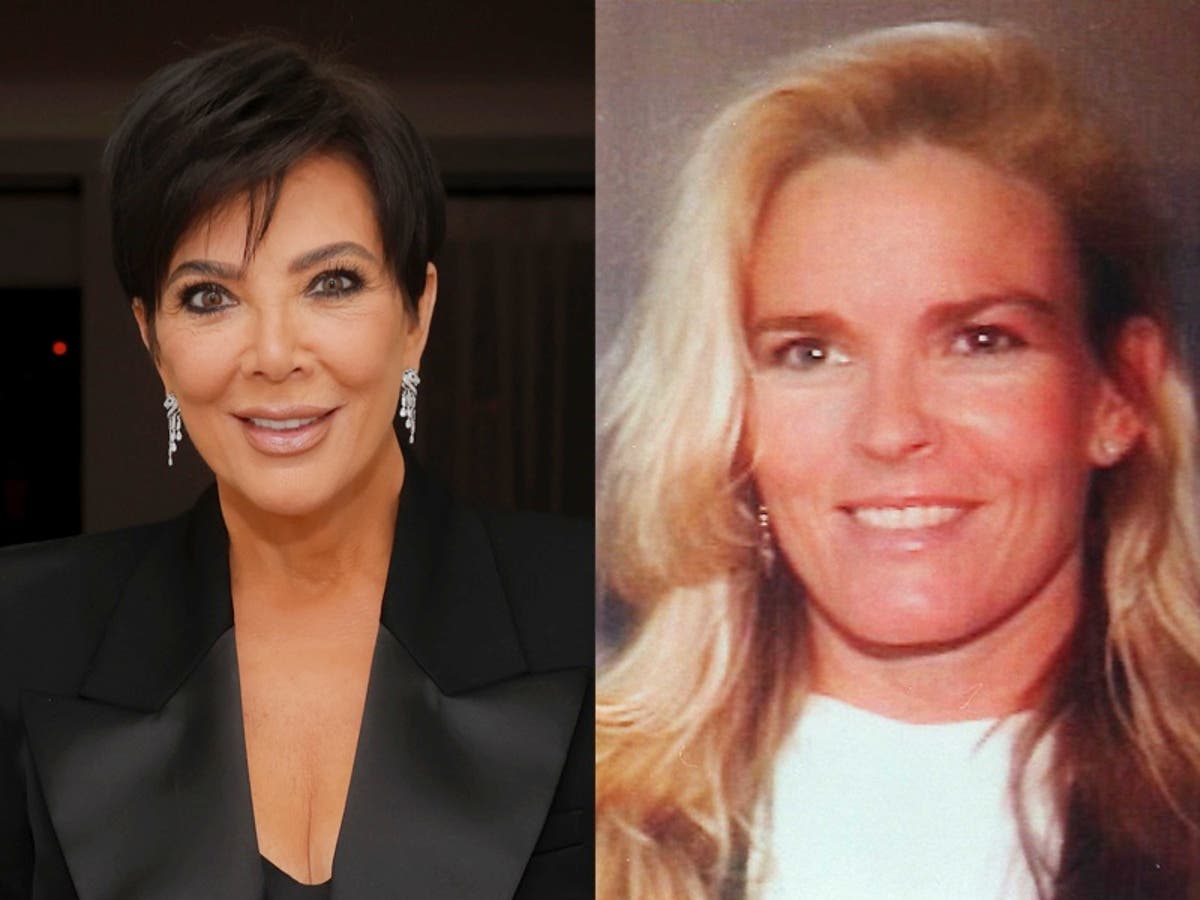

Harold Greene's Solieric Chaise Lounge is based on the Sun outside his San Pedro study.

(GL ASKEW II / FOR TIMES)

Greene had a seventh grade type class and was natural, but without a similar class in high school, the hobby escaped to university.

In Los Angeles Harbor College in Wilmington, he studied art, design and architecture with emphasis on interior design, along with music. In his first apartment, he realized that the furniture around him could be better, so he began building his tables and positions.

The friends who visited would notice the pieces and ask if he could also do something for them. In a short time, Greene was selling her work in local exchange meetings and taking the trade more seriously, teaching the techniques that would shape her career.

During these first years, before assuming full -time carpentry, Greene was also a musician. He played bass and sang support voices with bands around Los Angeles, including the R&B Magnum group.

Naturally, he has also made instruments. Greene said that the beauty and tone of an instrument come from the wood species used, and both matter greatly. For guitars, it favors the ash of the swamp for the body, “not too dense, or too thin,” and the harvest for the necks. The waves in the grain, he said, help the delayed notes.

Harold Greene manufactures small -scale furniture before building large -scale models. (GL ASKEW II / FOR TIMES)

For several years, the furniture was something next. He was not close to paying his rent. Then, when Greene was accepted in the fire department of the city of Los Angeles, she took the coveted and stable work.

His first year with the fire department left him without time to build, and began to lose his carpentry. “I felt that I was at a crossroads because I didn't know if I wanted to continue as a firefighter … the best job you could have,” Greene said. “Or make furniture again.”

-

Share by

He chose the latter, deciding that he did not want to be a firefighter with a “thing next to”.

“It was like a jump of faith,” Greene said. “I don't regret.”

Those first years were difficult. Greene scraped, often taking strange jobs and working long hours to meet the deadlines. He faced street fairs, gallery shows, commissions, anything to do his job. Little by little, the years of scraping gave way to stability.

One of those clients, one that continued to call some of Greene's most ambitious works.

Ken Pellman, the oldest client in Greene, first commissioned a small chuchery exhibition 30 years ago. Shortly after, Greene's work filled almost all the rooms in her old green stick house: lamps, shelves, an altar, a closet adorned with a lotus flower.

Harold Greene has created custom furniture for decades.

“I look at it every day and see something new,” Pellman said about the closet. “It makes me appreciate so much life.”

The two collaborated closely. Greene brought the trade and Pellman brought the ideas.

The most striking piece made for Pellman was a Japanese -style pergola that he used as a tea house. The project was a challenge from the beginning. The city would only allow a place on the ground, not two. Greene reinvented the engineering of the structure. He became not only a design feat, but also Greene's's favorite.

Even after Pellman moved to an apartment in San Pedro, he brought a large part of Greene's furniture with him. However, the beloved Pergola was left behind, located in the courtyard of its old house.

Another client, Dr. Venu Divi, a specialist in ear and throat of San Pedro, first hired Greene to design wooden panels for his office.

“He is a complete teacher of his trade,” said Divi.

Greene believes that the furniture has a story to tell: that each piece of wood has a life: where it grew, what it endured and in what it finally becomes. Wood, he said, has also told the story of his own life.

Harold Greene's Stewart dining chair in curly black walnut.

His wife, Kathleen Seixas Greene, has seen his trade evolve during his 43 -year -old marriage. “The pieces represent who we are,” he said. “From the toy box for our children to what they do now, they reflect where we are.”

His favorite is his outdoor table, which Greene elaborated with the excess teak and embedded with Gecko leaves, a wink to the favorite plant of her late mother. The table has become a meeting place.

Greene puts aside time every year to make a piece for her house in San Pedro. He has carved jellyfish at the closet gates and has recorded seaweed at the main door for his wife, who is an ocean swimmer.

Before Greene begins to draw and build a new project, spends time visualizing it, imagining how it could be seen. “Ideas: they are outside, somewhere, trying to take something that is in the ether and take it to three dimensions,” Greene said.

Greene, now in her 70 years, has no plans to reduce speed. Your workload is full. Your sketchbook is too. It is reserved for next year, and is thinking of new ideas and preparing to build a larger study.

“Never ages,” he said. “Why retire from something you love doing?”

In terms of carpentry, avoid table mountains because they interrupt their workflow, and favors carpentry intertwined by force.

Its material palette is wide but deliberate. Although it occasionally obtains wood worldwide, prioritizes sustainability through the purchase of local woods and urban wood suppliers. It also rescues the trees from the fallen street or the wood damaged by the storms.

Among his signature works is the Soliart Chaise Lounge, a limited edition of 100. In 1stdibs, it is sold for $ 5,000, while its dining room chairs cost $ 3,000 each. Its sculptural entry doors start at $ 6,000, and custom dining tables vary from $ 3,000 to $ 15,000.

Harold Greene is next to one of her personalized chairs outside her Study of San Pedro.

Even so, Greene values work more than sale. “I made many sacrifices for work,” he said. “I never let the quality of what I am doing slide, regardless of the cost.”

In recent years, Greene has assumed teaching in person, so she can transmit her knowledge to students throughout the country.

“I definitely want to convey the trade,” said Greene, who has taught in Penland School of Craft in North Carolina, the Furniture Handicraft Center in Maine and two Rock School of Woodworking in Petaluma, California, among others. He will teach next year at Austin School of Furniture in Texas and will speak at the Texas Carpentry Festival.

Most of the days you can find Greene working alone, although occasionally she works with an assistant. He prefers it that way.

“Fuel is work itself,” Greene said. “There is not enough time in one day and there is not enough time in my life to do everything I want to do.”

Throughout the carpentry years, Greene has been fond of working with private trees and their aromas. His favorite wood is “Hinoki”, commonly known as Port Orford Cedar. He said he has the most surprising smell.

But perhaps more than the aroma, shape or function of wood is what keeps underway: the opportunity to build something lasting. Not only to be looked at, but something to be lived, sitting, delivered to the next generation.

“Pay attention to details, those materials,” he said. “You are doing something that will last more than you.”