When Saul Leiter began photographing Kodachrome slides in New York in the late 1940s, color was despised by most serious photographers, seeing it as a pastime for vacationing parents or the commercial domain of magazines and advertising agencies.

But Leiter, who died in 2013, was a painter and photographer throughout his life. As shown in “Saul Leiter: Centennial,” an exhibition of photographs and paintings at the Howard Greenberg Gallery in Manhattan, which closes Feb. 10, and in a new monograph, “Saul Leiter: The Centennial Retrospective,” he took advantage of the filters everyday. (a window stained by drops of rain or moisture, flurries of snowflakes, reflections in the glass) to fragment reality into compositions that recalled paintings by the abstractionists who lived near his house on East 10th Street.

Although best known today for his innovative color photographs, Leiter employed similar strategies in his masterful black and white photography. He could devote two-thirds or more of the frame to a monochromatic block, inviting you to look with equal attention at the shadowy street in “Walking” (c. 1955) (in black and white) or the black cloth of the same name in (color ) “Canopy, New York” (1958), as you would with the subtle gradations of tone in a painting by Robert Ryman or Ad Reinhardt.

He loved women and he loved the color red. Judging by her photographs, you would surely come across a woman with a red umbrella if you ventured into a blizzard in 1950s New York. Part of her fondness for red may derive from Kodachrome's exceptional ability to capture its vitality. But at that time color photography had a serious drawback. Because prints were unstable and expensive, slides were usually viewed as projections on walls for friends and colleagues.

Although Leiter excelled in both formats, his prowess as a black-and-white photographer does not guarantee the same success in color, as demonstrated by a newly published collection of mostly unseen prints, “Winogrand Color” (Twin Palms Publishers, 2023), shows. Garry Winogrand, a black-and-white photographer who captured the bustling street ballet like no one else, became weaker and weaker when he worked in color, at least in the images selected for the book by Michael Almereyda and Susan Kismaric. (They also collaborated on a 2019 Brooklyn Museum exhibition led by curator Drew Sawyer featuring more than 400 Winogrand color slides; though memorable as a whole, the exhibition was difficult to remember in particular.)

Joel Meyerowitz, a noted photographer who has photographed in color since 1962, often accompanied Winogrand on his weekend photography forays, with Winogrand's girlfriend and their two children. Winogrand gravitated toward places attractive to children: Coney Island, Central Park, the zoo. He held one camera loaded with black and white film and another with color film. He called the second “his touchy-feely camera of his,” Meyerowitz recalled in a recent telephone interview.

Winogrand, who died in 1984, aged 56, had an astringent view of the world that did not benefit from the infusion of color. While William Eggleston's early black-and-white photographs, despite their astute composition, look like neon signs awaiting the electrical charge of color, for Winogrand it was painting the lily, adding an unnecessary element to something fully formed.

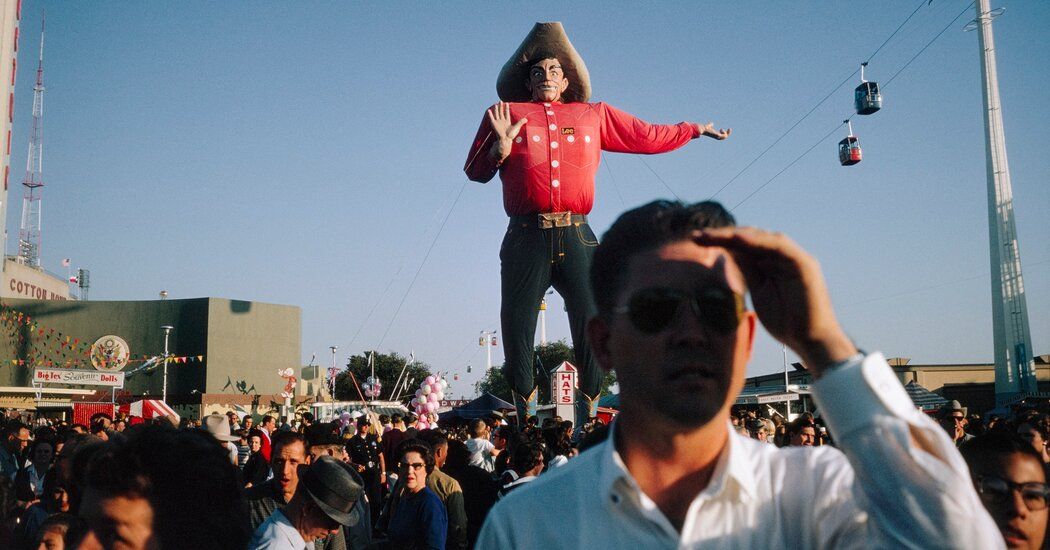

His black-and-white photograph of Big Tex, the cowboy effigy that looms over the State Fair of Texas in Dallas, shows a motley assortment of Texans sitting and frolicking beneath the absurd figure. In the color variant, much of the space is taken up by a blank blue sky and the visitors are confusing, so the comedy wears thin. Even less successful is the color version of one of his most famous photographs, “Central Park Zoo, New York City” (1967), which shows a black man and a blonde woman, apparently wealthy, each carrying a chimpanzee. fully dressed. It is a scathing and disturbing commentary on the era's prevalent insults about interracial marriage. In the color image, probably taken an instant later, the man looks at the camera, the woman's expression has changed, and the impact is blurred by the photographer's own shadow and a crowd of distracting passersby.

The best photos in the book are anomalous. The previously published “White Sands National Monument, New Mexico,” (1964), transposes Winogrand's fascination with alienated and isolated Americans into a beautiful blue-and-white image. And some of the earliest photographs of him from Coney Island, taken in the 1950s, use color to convey the tender vulnerability of sand-marbled flesh.

However, in my opinion, Winogrand's best color photograph was made not by Winogrand but by Fred Herzog, a still underrated Vancouver-based artist who began taking color photographs in 1953 and continued to do so for 20 years. In the close-up of “The Bandaged Man,” 1968, a middle-aged man, wearing a white T-shirt and holding a cigarette in his bandaged left hand, raises his right arm, which has a visible bruise. Behind him, at the bus stop, an elegantly dressed older lady looks at him disapprovingly. It's exactly the kind of humorous urban juxtaposition that Winogrand loved to depict.

But Herzog makes the most of the color red. A blood-soaked piece of handkerchief on the man's chin is picked up by the shaded awning of the hotel on the left, by the bus sign above the woman, and, most of all, by the bright red mailbox he is holding on the right. frame quarter. In this image free of sensitivity, color increases tension. It is as if Herzog heard notes at a frequency that Winogrand did not pick up.

Saúl Leiter: Centennial

Through February 10, Howard Greenberg Gallery, 41 East 57th Street, Manhattan; 212-334-0010; howardgreenberg.com.