I read the news today, oh boy.

John Lennon’s lyrics came to mind on Tuesday as soon as I read my friend Marcy Carriker Smothers’ texts. The first was a photo of a guitar next to a fire and a Christmas poinsettia. The second included the news. “Beautiful and peaceful passage today at 1:40 pm We had a wonderful Christmas.”

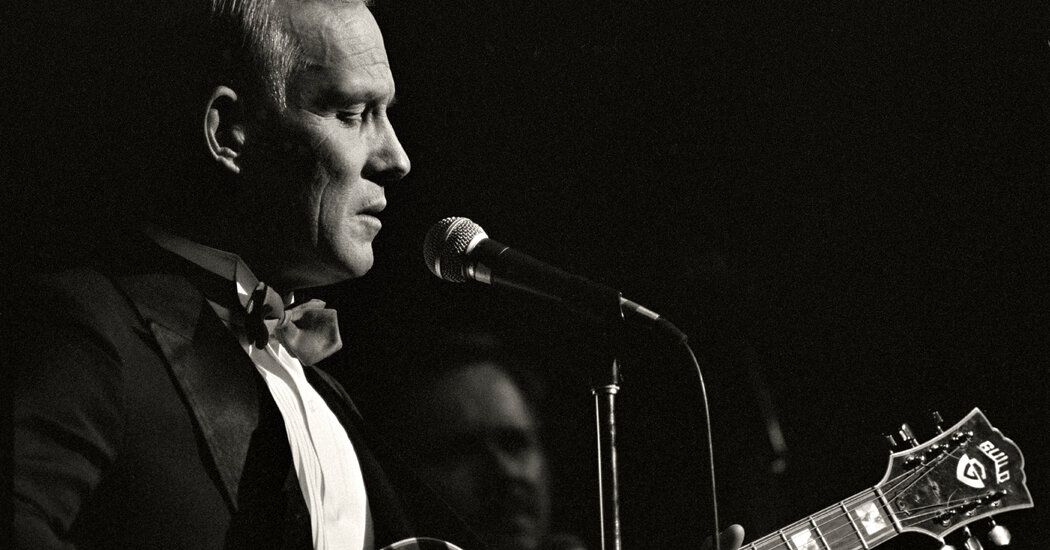

Tom Smothers had been in hospice for months, so the news of his passing brought a sigh, not a gasp. I thought of the lyrics to “Day in the Life” not because of the circumstances of his death (Tom was 86 and died of lung cancer) but because Lennon and Tom were close. On the recording of “Give Peace a Chance” in Montreal in 1969, only two acoustic guitars were strumming. One is in Lennon’s hands; the other by Tom.

Tom came to the anti-war movement with sad good faith. His father was a West Pointer who said goodbye to his namesake son in 1940, before heading to the Pacific to defend freedom. He never returned.

There’s nothing funny about that origin story. Still, through music, Tom and his younger brother, Dick, found their way into comedy and created an act that instantly impressed Jack Paar, the host of the “Tonight” show, who commented in 1961: “I don’t know What do you have? But no one is going to steal it.”

Six years later, the brothers premiered “The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour,” their seminal variety show that used comedy to satirize topics such as the Vietnam War, racial politics and drugs.

Despite the heavy themes, Tom was happy and simple. During an audience question-and-answer session, a woman once asked, “Are you both married?”

“No, ma’am. We’re just brothers,” Tom said.

In real life, Tom thought and felt deeply. He cared about social justice and the creative process. He worked on the details. The biggest contradiction was Tom’s stage persona. A classic Smothers Brothers sketch would begin with the two singing a song until Tom would interrupt or mess up the lyrics so much that Dick would tune out. This would lead to ironic remarks or an argument that would end in a punchline. The brothers would then return to the song, giving the sketch a natural and satisfying ending. At its core, it was a character comedy with Dick playing bass and being the straight guy and Tom playing guitar and being a fool.

In one of the first episodes, the brothers came out singing Maurice Chevalier’s hit, “Louise,” while wearing boaters. They paused to talk French and romance, and Tom instantly He claimed familiarity. “Do you really know those French wines and women?” Dick challenged Tom.

“Oh, I know all about that stuff.”

The audience laughed, doubting his statement.

Dick wasn’t about to let Tom off the hook. “French wine, what do you know about it?” he pressed him.

“It gets you drunk,” Tom replied, nailing the shot with exquisite timing.

In real life, Tom knew everything about wine. For decades, he owned and operated a vineyard in Sonoma that produced award-winning merlot and cabernet sauvignon. At first, he lived in a barn on the property, then designed a main house with a huge stone fireplace and views in all directions so he could follow the sun all day long. If the hot tub could talk, he would tell racy stories about parties in the 1960s and 1970s and he would probably be the only one who could remember what happened.

When I visited Smothers-Remick Ridge Ranch, the hot tub was a place for the kids to splash around. Yo‘I first met Tom in 1988, when I was hired as a writer for the variety show Second Life. While working on the reboot, I shared a room with associate producer, Marcy Carriker, who married Tom in 1990. Their two children, Bo and Riley Rose, would play with my two children. Marcy co-hosted a food and wine radio show with Guy Fieri, so dinner was always delicious. After dinner, Tom would sit by the fire and read a thick novel.

It was an image of domesticity that did not last. Immersing yourself in wine country meant drinking a lot, and the more Tom drank, the less fun he became. Knowing how brilliant and generous he could be, it was painful to see how his demeanor changed. If this seems harsh, I mention it because Tom cared about the truth. Marcy and I would take long walks to discuss the situation. We came up with a phrase that summed things up: “It’s complicated.”

Tom and Marcy separated 15 years ago but never divorced. And when Tom got sick, she was there for him along with his children. “They were stones,” Marcy texted me hours after her death. She told me that over the past few months, Tom had never had a stranger take care of him. She, Bo, Riley Rose and Marty Tryon, Tom’s former road manager, took care of him.

And so Tom spent a beautiful Christmas Eve and a wonderful day surrounded by his family. He escaped the next afternoon. As always, exquisite timing.

I hope Tom is remembered. He last appeared on television three decades ago, so outside of comedy nerds, no one under 40 would have reason to recognize him. If you’re curious, there’s a clever 2002 documentary, “Smothered,” about the brothers’ firing from CBS, and an excellent book by David Bianculli, “Dangerfully Funny: The Uncensored Story of the Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour.” Both the movie and the book reiterate what history has made clear: Tom was absolutely right that war is stupid and that civil rights are worth fighting for. In his own way, he also defended freedom.

Or try sliding down a YouTube rabbit hole where you’ll stumble upon the early routines of Steve Martin, whom Tom hired as a writer before encouraging him to perform. I’ve never met an artist who was more respectful of other people’s talents than Tom. I adored many fellow artists, including Harry Belafonte, Harry Nilsson, Martin Mull, and (Mama) Cass Elliot, who illuminates one of my favorite sketches from the 1968-69 season.

The concept is simply Elliot singing his hit “Dream a Little Dream” to Tom while he tries to fall asleep in a big brass bed. Tom doesn’t say a word but he laughs a lot. The part is sweet, original, musical and fun. When you strip away the implications, Tom was all of those things.