The proliferation of documentaries on streaming services makes it difficult to choose what to watch. Each month, we’ll choose three nonfiction films (classics, recent overlooked documentaries, and more) that will reward your time.

‘Sympathy for the Devil’ (1970)

Rent it on Amazon and Apple TV.

The best-known documentary about the Rolling Stones is almost certainly “Gimme Shelter,” the Maysles brothers’ chronicle of the band’s 1969 concert at the Altamont Speedway, a film that infamously captured the fatal stabbing of a concertgoer. But the strangest documentary in which the Stones have appeared is “Sympathy for the Devil,” first screened in 1968. The director was none other than Jean-Luc Godard, in the process of oscillating between the brilliance of “Weekend” and the politicized one barely visible. films that he would make with what was called the Dziga Vertov Group. In the recent documentary “Cine Godard”, “Sympathy for the Devil” is presented as the director’s last bourgeois film before the breakup.

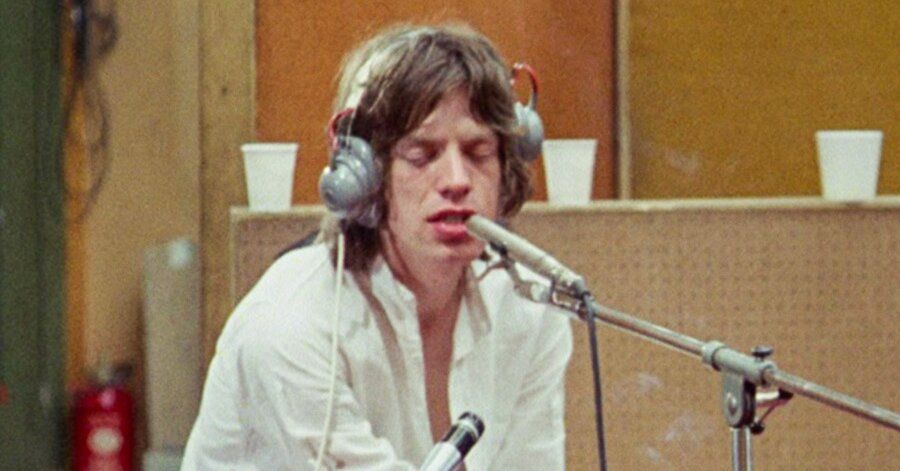

Much more interested in process than product, “Sympathy for the Devil” cuts back and forth between the Stones in the recording studio as they refine what would become one of their best-known songs and the scattered material Godard filmed around London. . The study sessions are hypnotic; The camera pans around the room in long takes as the Stones try to find a rhythm, though they are often undermined by a tinny voiceover of what Roger Greenspun, reviewing the film for The New York Times in 1970, described as a “ today famous pornographic political novel”, whose text Godard uses as an effect of alienation.

Between clips of the band, Godard intersperses various provocations: scenes of black militants operating from a scrapyard by the Thames; a strange interlude in a bookstore and magazine where a man in Elton John-style glasses reads “Mein Kampf” and saluting Hitler appears to be part of the checkout procedure; and Godard’s then-wife, Anne Wiazemsky, playing a person named Eve Democracy, who answers yes or no (mostly yes) to nonsensical questions from a television reporter. The graffiti and hand-painted titles are part of Godard’s usual wordplay, although this time in English (“FBI + CIA = TWA + PANAM”). An uninterrupted close-up plane exposes the tracking, lifting and tilting machinery.

The version that is transmitted is technically not Godard’s. Theirs was titled “1 + 1” (or “One plus one” or “One + One,” depending on the source), apparently for the idea of bringing together contradictory ideas. He didn’t play the full Stones song until the end. Richard Brody’s comprehensive book on Godard, “Everything Is Cinema,” gives an account of how the two versions of the film at one point were intended to be screened in counterpoint at the 1968 London Film Festival. In New York, “Sympathy for the Devil” and “1+1” alternated days. “If you go on Monday, Wednesday, Friday or Sunday, you will see Godard’s film,” Greenspun wrote.

‘The last of the unjust’ (2014)

Stream it on Kanopy. Rent it on Amazon, Apple TV, Kino Now and Vudu.

“The Last of the Unjust” is one of several films by Claude Lanzmann (1925-2018) that can be considered an offshoot of “Shoah” (1985), his nine and a half hour film about the Holocaust that, for many, represents the best cinematographic statement on the subject. “The Last of the Unjust,” completed nearly three decades later, revolves around a series of interviews Lanzmann conducted in Rome in 1975 with a former Vienna rabbi named Benjamin Murmelstein.

Murmelstein was the last president of what the Nazis called the Jewish Council of Theresienstadt, the exhibition camp they had established on the outskirts of Prague to flaunt their seemingly humane treatment of Jews to the world. He basically functioned as an intermediary between the Jews and the Nazis in the camp. Inevitably, after the war, he was accused of collaboration. Murmelstein’s description of his role is a little different. He says that the “elder” of a council (the German term, which Lanzmann said had tribal connotations) was always “between the hammer and the anvil.” Murmelstein adds: “The person in that position can cushion a lot of blows.”

Exactly how many blows he cushioned, how he did it and why are the essential questions that Lanzmann reveals throughout the film. Murmelstein, who had already been commissioned by Adolf Eichmann in Vienna to investigate the issue of emigration, had the opportunity to flee to London in 1939 and did not do so. “Do you want me to admit that I felt like I had a mission to fulfill and that’s why I didn’t leave?” he asks Lanzmann. “That seems so strange?” He admits that he had what he calls a “thirst for adventure” and does not deny his taste for power. But if his position allowed him to obtain more visas for more Jews from the British consul, so much the better.

He strongly rejects Hannah Arendt’s description of Eichmann as the embodiment of the “banality of evil.” (“He was a demon,” Murmelstein says.) His memories of Theresienstadt become, in fact, the story of his efforts to bolster the Nazis’ propaganda efforts in order to save more lives by saving the camp. “If they hid us, they could kill us,” he says. “If they showed it to us, they couldn’t. Logical! “The fact that 33,000 Jews died in Theresienstadt, according to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, might give some idea of the grim reckoning he faced.

Lanzmann, who supplements the 1975 conversations with current visits to the places in question, clearly likes Murmelstein, who died in 1989. The film’s farewell note, with the men drifting away in friendship, only adds to the complexity of the emotions. . the film evokes.

‘Street Gang: How We Got to Sesame Street’ (2021)

Stream it on Max. Rent it on Google Play and Vudu.

Last month in The Times, Sopan Deb learned how Cookie Monster cookies are made. What happens behind the scenes of “Sesame Street” is an endless source of curiosity, especially since most of its viewers watch it before they start thinking about how television shows are made.

“Street Gang: How We Got to Sesame Street,” a documentary by Marilyn Agrelo (“Mad Hot Ballroom”), is inspired by and its title is inspired by a book by Michael Davis. But you can’t really tell the story of “Sesame Street” without clips, and that makes this documentary hard to resist. Who today (or really ever) would think of taking tried and true advertising methods and directing them toward educational purposes? “Every kid in America was singing beer commercials,” says Joan Ganz Cooney, the first executive director of the Children’s Television Workshop. “Where did they learn beer commercials?”

Jon Stone, the show’s longtime writer, producer and director, remembers that the idea for the brownstone set came from an Urban Coalition commercial. (The reasoning is that any city kid would know that the streets are more fun than being locked up upstairs.) The show depicted a multiracial neighborhood long before it was fashionable to show one on television. And some of the most fascinating details recounted in the film have to do with “Sesame Street’s” sensitivity to child psychology. When actor Will Lee, who played Mr. Hooper, died, the show’s creators made Mr. Hooper’s death part of the show, in part because doing it any other way would have broken the show’s spirit of being honest with kids. .