Donato Martínez reads his poetry at the Libros Lincoln Heights bookstore.

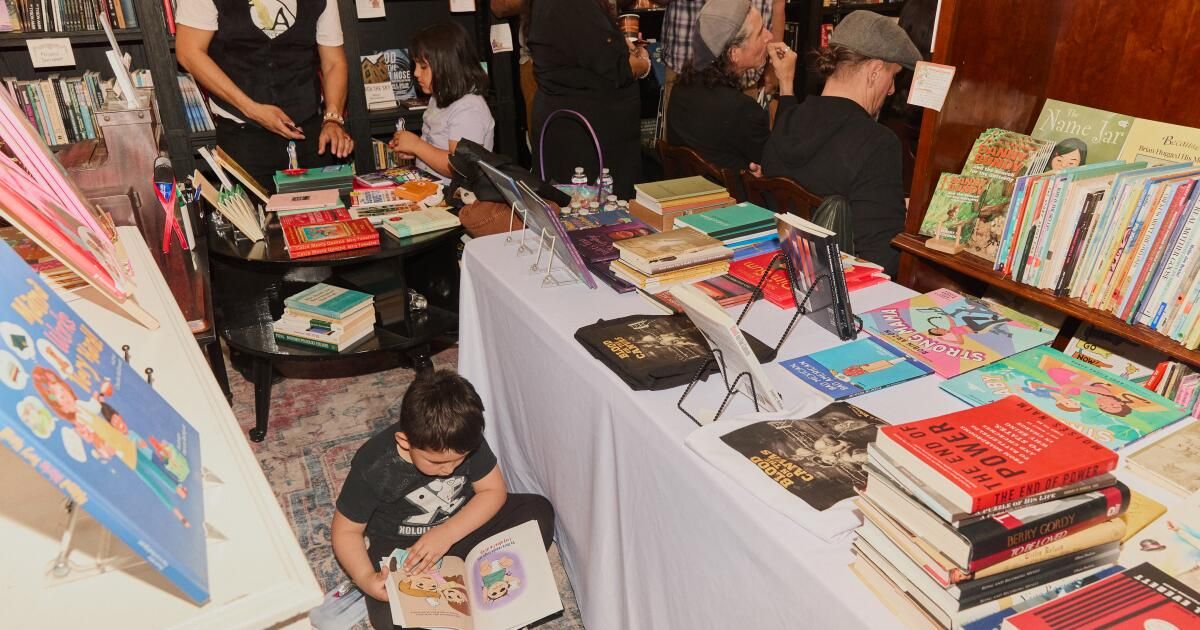

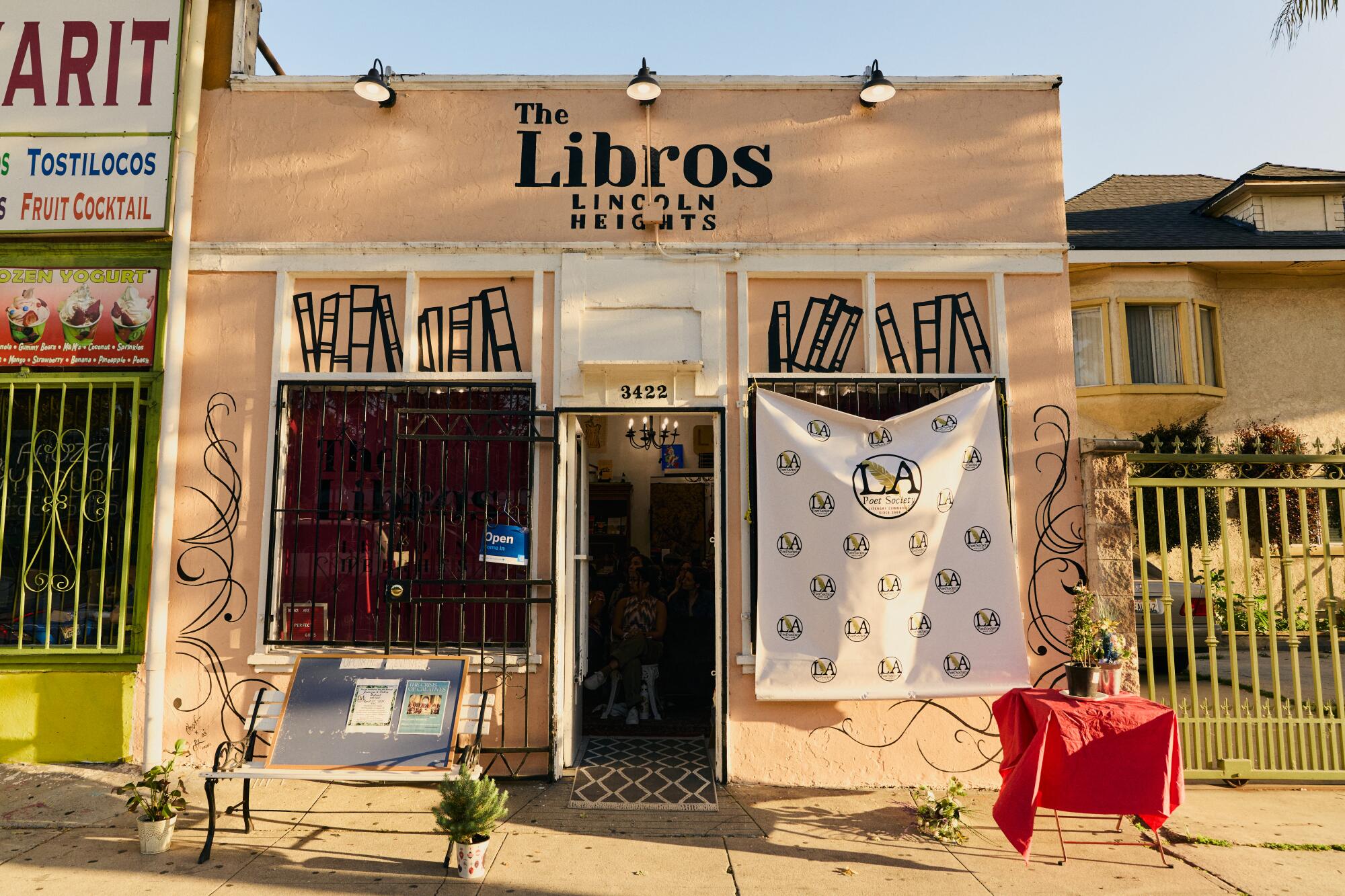

On a Saturday afternoon in late April, the door to Lincoln Heights Books is open. Inside, 18 local poets fill the narrow, one-room bookstore, waiting for the chance to read a poem or two at this month's open mic in front of an enthusiastic audience.

Donato Martínez, an English professor at Santa Ana College, is the third poet to take the podium. He reads from a pile of loose papers, his hands moving to the rhythm of the verses he spits out like rap bars.

“All street vendors are allowed. / Taco stands that never close / Free zone at any time / Patrolled by ours. That means Elotes. Churros. Bacon-wrapped hot dogs/Fruit cocktails anytime,” Martínez recites from his new poem, titled “If I were God, I would visit the neighborhood.”

The audience clicks and hums, overlaying their own harmony to the soft hum of the ceiling fan and the cars racing down North Broadway.

Martínez's poetry collection “Touch the Sky” can be found on surrounding shelves, along with collections from three other readers of the night. Her presence speaks to the driving spirit behind the Books: between 80% and 90% of the merchandise on the bookstore's mismatched shelves are written by residents of Lincoln Heights and nearby neighborhoods.

“I don't just have a small shelf for local authors. The whole place is made up of local authors,” said Jesse Marez, owner of Libros. “It integrates with the neighborhood.”

Marez, an electrical engineer by training and lifelong book lover, opened Libros last November, in an effort to consolidate the shelves he had been curating in cafes across the East Side since late 2021. He estimates it is the first bookstore in Lincoln Heights. in more than 70 years.

A Books sticker on the store door.

Drinks at the open mic poetry reading.

Growing up in Lincoln Heights and neighboring El Sereno, where his family settled after emigrating from Mexico in 1969, Marez experienced this scarcity firsthand. Now it is determined to at least be a place where local authors can share their stories and readers can find a book in a variety of languages and genres.

“We didn't grow up going to a bookstore or having books, so to me I think it's valuable for a child,” Marez paused, ducking her head to wipe away tears. “I think it's important for them to know that they can have their own book and that it shouldn't be a used book because we are all used to used things. “I think in a neighborhood like this, people need to know that they can get a new book, especially at a young age.”

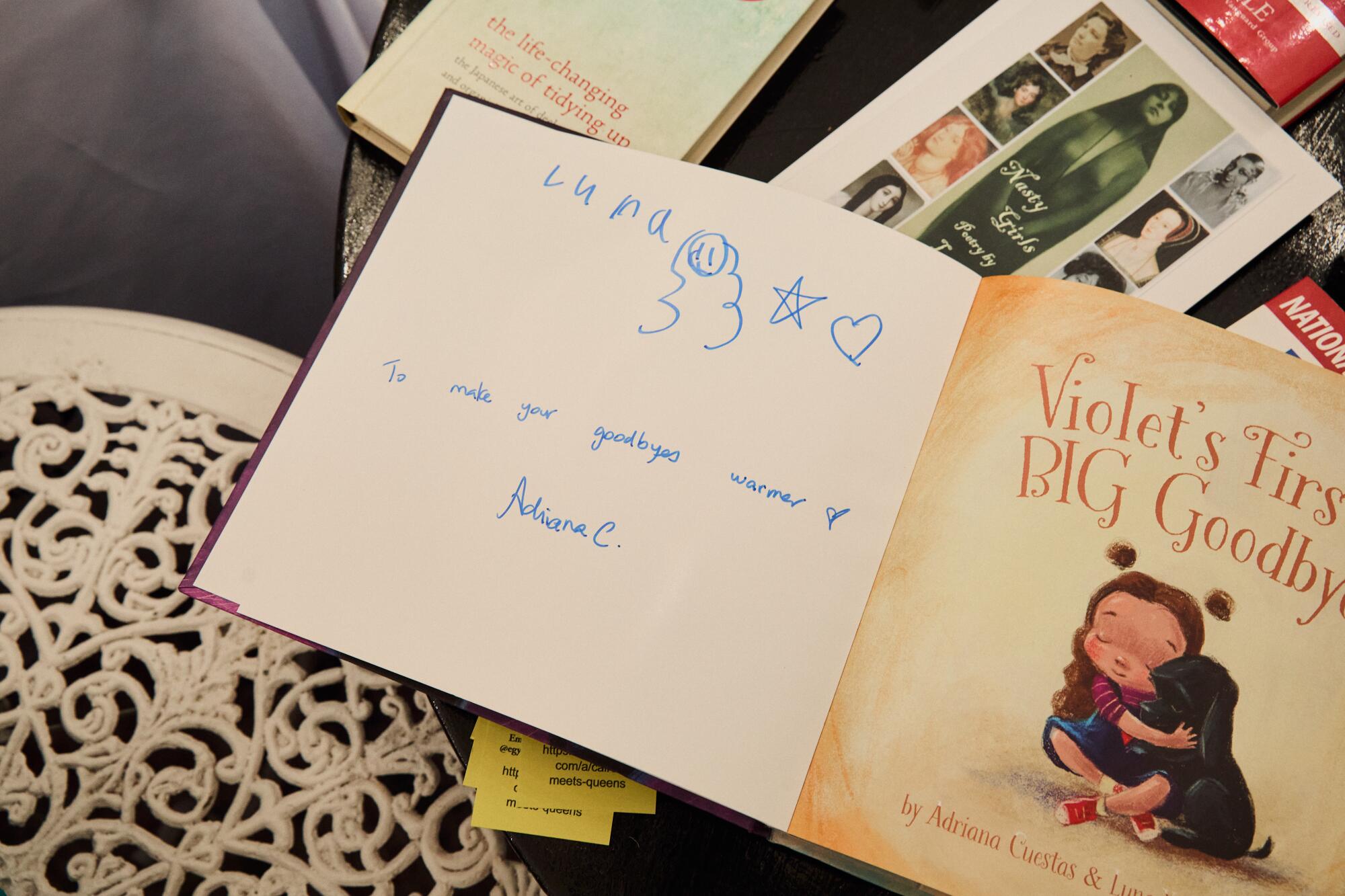

In the months since its opening, Libros has become a neighborhood hub, highlighting books and authors that can't always be found on the shelves of other bookstores. Collections of poetry and self-published family stories from Lincoln Heights sit alongside multi-award-winning books by Viet Thanh Nguyen and Kelly Lytle Hernandez (also Los Angeles residents). On a table in the center of the room are copies of “Violet's First Big Goodbye,” an illustrated book written by the bookstore's youngest author, 8-year-old Luna Yánez-Cuestas.

Yanez-Cuestas, who lives in Burbank, wrote and published the book with her mother, Adriana Cuestas, to share the pain she felt after saying goodbye to her old neighborhood.

“It's about saying goodbye to what you really love,” Yáñez-Cuestas said.

A signed copy of “Violet's First Big Goodbye” by Luna Yánez-Cuestas sits on a table in the Libros bookstore.

Customers come to the store looking for this wide selection of books, many of which have been signed by their authors. Marez said most of the books sell quickly because they are local.

Readers aren't the only ones who frequent the store. Authors regularly stop by with books under their arms and timidly ask if Marez will sell his collection of memoirs or poetry. Their answer is always an enthusiastic yes, even as shelf space becomes increasingly limited.

Marez also has a knack for finding local writers. He met Lluvia Arras, the Los Angeles-based author of “A Children's Book about Blended Families,” when her children were playing soccer together. A few months later, he connected with Joseph Robledo at an exhibition at the Olympic Auditorium of La Plaza de Cultura y Artes.

Robledo is the author of “Blood on the Canvas,” a book that commemorates his father, a local boxing legend Singing 'TNT' Robledo. The son of Mexican immigrants, the elder Robledo became an amateur boxer at age 15, turned professional at 16 and won the Pacific Coast Bantamweight Championship at 19. He was on his way to the world championship when a A series of injuries left him permanently blind.

“Blood on the Canvas” guides readers through gyms in South Pasadena to the World Boxing Hall of Fame to tell the story of his father's transformation from aspiring champion to the inspirational trainer who touched the lives of hundreds.

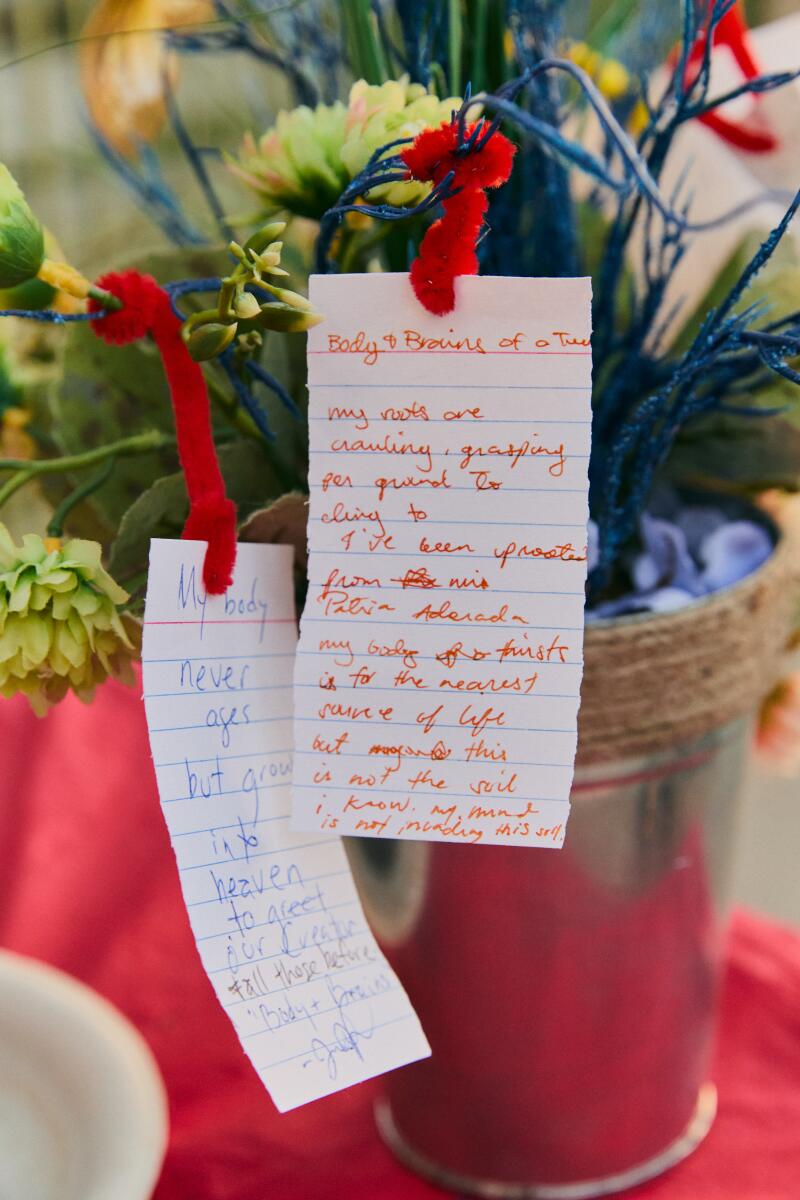

Attendees write poems during a poetry reading and open mic night at Libros Bookstore.

Attendees place their poems on plants outside the Libros bookstore.

Meeting authors like Robledo and Arras has drawn Marez to the literary world of Los Angeles and taught him tricks of a trade that is often opaque to outsiders.

Behind every book on the store shelves is a journey full of obstacles. Is challenging break into the conventional publishing world and, according to a new surveythe industry remains overwhelmingly white.

“I was obsessed with self-publishing because I thought, based on how I hear things for authors in our society, it just didn't seem fair to give such a large portion of your work to someone else,” Cuestas said.

For these reasons, authors like Cuestas turn to self-publishing or self-publishing to make their books known to the world. The latter, which has recently become increasingly Popular, it gives authors creative control and the potential to earn a larger share of the profits, said Brenda Vaca, a Whittier-based author who created her own publishing company to publish her poetry collection titled “Riot of Roses.”

But that creative control comes at the cost of playing all the roles: writer, editor, distributor and marketer. Stewart J. Zully, who published his memoirs about the 40 years he spent selling at Yankee Stadium, says he has spent much of his writing career working alone and waiting for a break.

“Creativity and work [to get] what you do is one side of the brain and then the business side is completely different,” Zully said.

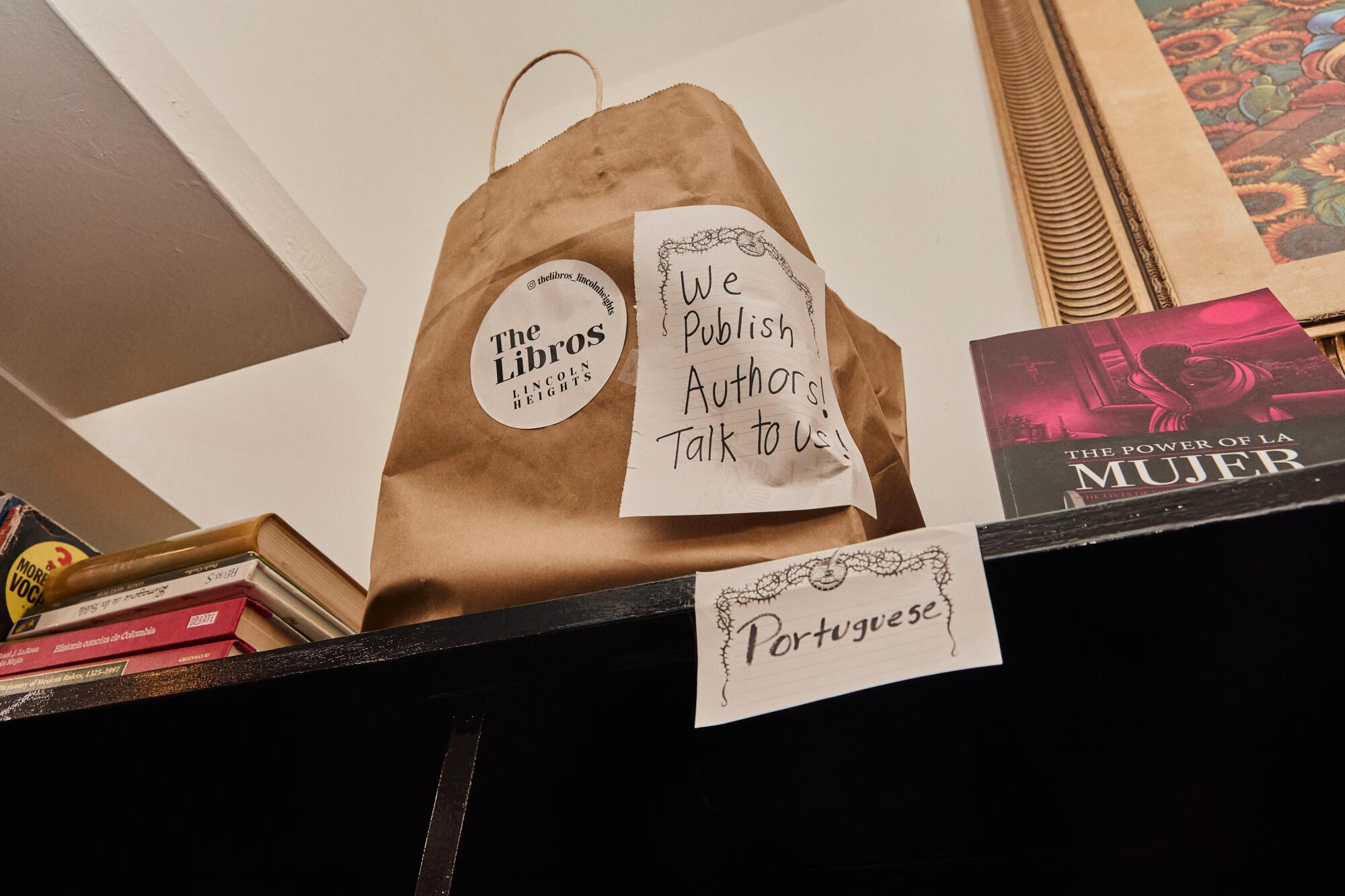

In Books, Marez is trying to take some of these hats off of authors by launching his own publishing company, Legacy Publications.

A paper bag with a sign that says “We publish authors, talk to us” sits on top of a shelf in the Libros bookstore.

“What we're trying to do is help these authors with distribution, printing and publishing,” he said. “Because they're more worried about how to make a dollar or how to do distribution, when they should be worrying about their second book.”

Like the bookstore, Legacy Publications is deeply rooted in Marez's pride in the eastern neighborhoods in which he grew up.

“I want to feature people who have really been a part of our community,” Marez said. “We want to talk about people who have left a legacy in our neighborhoods.”

By launching this new arm of the business, Marez aims to highlight local voices, help authors make a profit, and ensure books are made with high-quality materials. He prioritizes working with local presses like Litho Press and Paperleaf Press and plans to publish at least three books in the new year.

In his dual role, Marez is filling Lincoln Heights with books that take readers to distant countries and times, opening up new worlds. Alongside them are stories that bring readers home with untold stories of the neighborhoods that raised them and their families. The authors themselves find comfort in knowing that, at least in Books, their books will be read and shared.

“Our books don't appear in Barnes & Noble,” Martinez said, referring to how stories by authors of color have largely been out of the main publishers and, therefore, of the bookstores, for generations. “I wish they did and I think our stories belong there. If they're not at Barnes & Noble, we need these independent bookstores to house our books. We support Libros and then Libros provides a safe space for writers and poets. I think there is a relationship there.”