Last update:

What happened to the royal and temple jewels of India during British colonial rule and invasions?

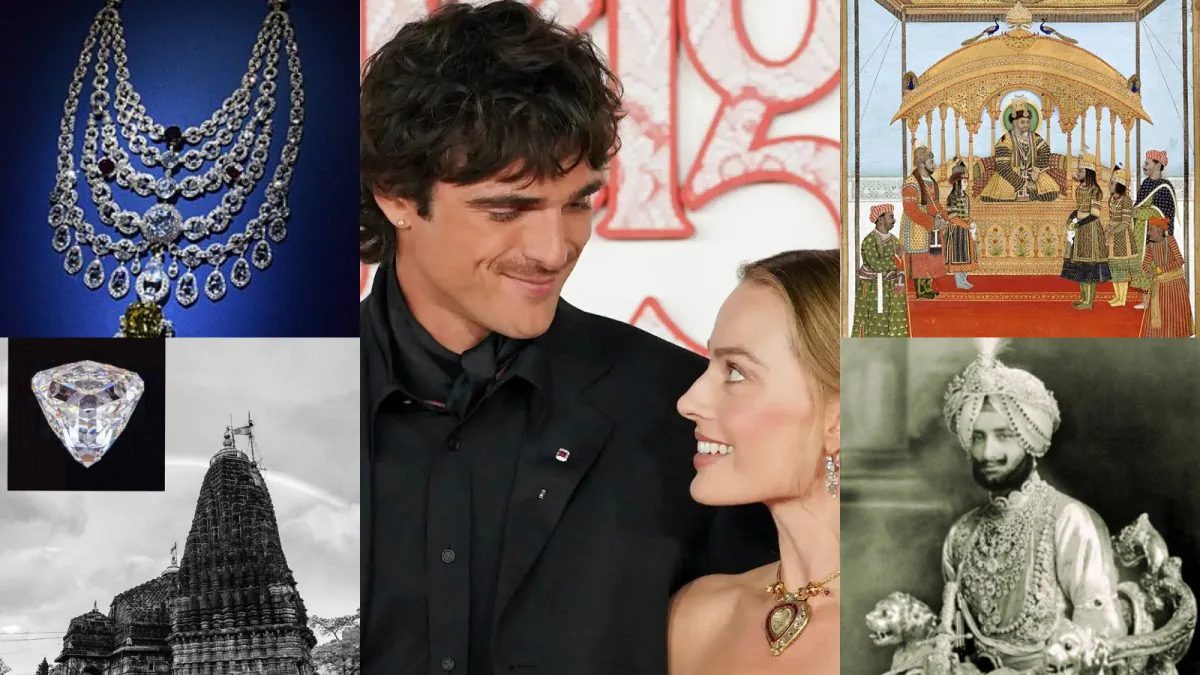

The Peacock Throne, Koh-i-Noor and Now Margot Robbie's 'Taj Mahal' Diamond: How India Lost Many of Its Most Iconic Jewels. Credit: Wikimedia Commons/X

From sparkling turban stones and temple “eyes” to Cartier pieces and the British Crown Jewels, many of South Asia's most famous gems crossed continents during the 18th and 19th centuries. Some were war booty, others diplomatic “gifts” made under duress; some were sold in the London diamond markets. The headlines continue to make, most recently when Margot Robbie wore a vintage Cartier “Taj Mahal” necklace of Mughal provenance to a film premiere, sparking new debates about provenance, empire and the ethics of wearing historical jewelery today.

Margot Robbie in Elizabeth Taylor's Taj Mahal Diamond: from the Mughal legacy to the other side of the seas

The heart-shaped diamond, which is from Elizabeth Taylor's extensive jewelry collection, is engraved with the words “Love is Everlasting” along with the name Nur Jahan. Historians believe that the gem was gifted by Mughal Emperor Jahangir to his wife Nur Jahan, and then passed on to his son, Emperor Shah Jahan, who gave the diamond to his beloved wife, Mumtaz Mahal. When she died in childbirth in 1631, he was devastated and built the Taj Mahal in her memory.

In 1971, Cartier acquired the gem and created a necklace inspired by traditional Indian design, which found its way to Elizabeth Taylor and now Margot Robbie.

Patiala Necklace: Maharaja Bhupinder Singh's Cartier Masterpiece

The Patiala necklace was born as a 1925 Cartier commission to Maharaja Bhupinder Singh of Patiala: a decadent order that included thousands of diamonds and large colored stones assembled into a multi-strand necklace. After the collapse of the princely order of India and the dispersal of royal treasures, parts of the necklace disappeared and some stones later appeared at auctions and in private hands. In the late 20th century, Cartier reconstructed the surviving mountings (using replicas with missing stones) and the recreated piece became an emblem of both princely splendor and the messy afterlife of colonial-era jewelry scattering.

The Peacock Throne: Mughal Majesty and the First Great Scattering of Jewels

Shah Jahan's legendary Peacock Throne was the height of the Mughal court's opulence: an ivory and gold structure with dozens of famous gems that symbolized imperial power. When Nader Shah of Persia sacked Delhi in 1739, the throne's treasures were taken to Persia; Many individual stones from that hoard later appeared in other royal hoards in Asia and Europe. The sack of Delhi shattered Mughal wealth and set a pattern: Mughal gems, once centralized, became scattered loot, then moved again as empires expanded and changed hands.

Koh-i-Noor: from the Mughal turban to the British crown jewels

The Koh-i-Noor is perhaps the most controversial stone associated with India's imperial past. It passed through the treasuries of the Delhi and Mughal Sultanate before reaching the Sikh court. After the Second Anglo-Sikh War (1849), the young Maharaja Duleep Singh was forced, under the terms of the treaty, to part with the diamond; It was presented to Queen Victoria and then cut out and embedded in British royal jewelry. The story of the Koh-i-Noor is as much about geology as it is about power: its modern home in the Tower of London remains a focal point for claims and calls for repatriation from India, Pakistan and Afghanistan.

Darya-i-Noor: the pale pink giant

The Darya-i-Noor (Darya-ye Nur) is a rare pale pink diamond, one of the largest in the world of its color, which is today in the national treasury of Iran. Scholars trace its origins to the same legendary Golconda mines that produced many famous Indian diamonds. The Darya-i-Noor entered Persian collections after Nader Shah's invasions and Qajar monarchs subsequently placed elaborate frames around it; It remains on display in Tehran as part of Iran's imperial jewels. Its story illustrates how stones looted from India in the 18th century became part of the crown collections of other nations.

The Nashik diamond and other temple stones

Stories of gems set in temples, eyes and crown stones in idols appear repeatedly in gem lore. It is widely known that many temple jewels were appropriated during colonial wars and market sales, then cut up and sold in London and Paris. The Nassak (Nashik) diamond, mined from the Trimbakeshwar Shiva temple in the early 19th century and sold in the London market, is one of the examples of the long migration of a temple gem.

February 4, 2026, 20:57 IST