It's just after 9:30 a.m. on a recent weekday, and hairnet-wearing workers in the Alhambra Unified School District's central production kitchen are packaging the last 350 hand-rolled sushi rolls for the city's three high schools.

Spicy tuna rolls, which smell like cooked fish mixed with sriracha and mayonnaise, are a popular lunch among students.

“It's one of our signature items that you can never take off,” said Dwayne Dionne, culinary specialist for the Alhambra Unified School District.

-

Share via

Alhambra Unified has been selling sushi for about 25 years. At one point, the district switched from white rice to brown rice, a healthier whole grain. However, it is the type of food that will be scrutinized under a new state law: the Real Food, Healthy Kids Act.

The law, which Gov. Gavin Newsom signed Wednesday, provides a legal definition of ultra-processed foods in the United States for the first time and will ban some that are “cause for concern” in California schools starting in 2035.

Under the legislation, which is expected to trigger a major overhaul of school cafeteria meals, the state Department of Public Health will identify ultra-processed foods “of concern” and “restricted school foods” (another banned category) by 2028. A year later, schools must begin phasing them out.

“There's a huge opportunity to help a lot of people in a pretty simple way,” said Assemblyman Jesse Gabriel (D-Encino), author of the legislation. “I'm still learning about all this… [was] “I was going to the grocery store trying to do the right thing for my kids, but I had no idea that we could be feeding them things that could be harmful.”

For years, scientific studies have shown that ultra-processed foods can cause significant health problems among children, increasing the risk of obesity and asthma. Ashley Gearhardt, a psychology professor at the University of Michigan, said children are particularly vulnerable to “high-risk” ultra-processed foods that offer “really unnatural levels of rewarding ingredients like refined carbohydrates and added fats, and… they're being amplified with all these colorings and preservatives and flavor enhancers.”

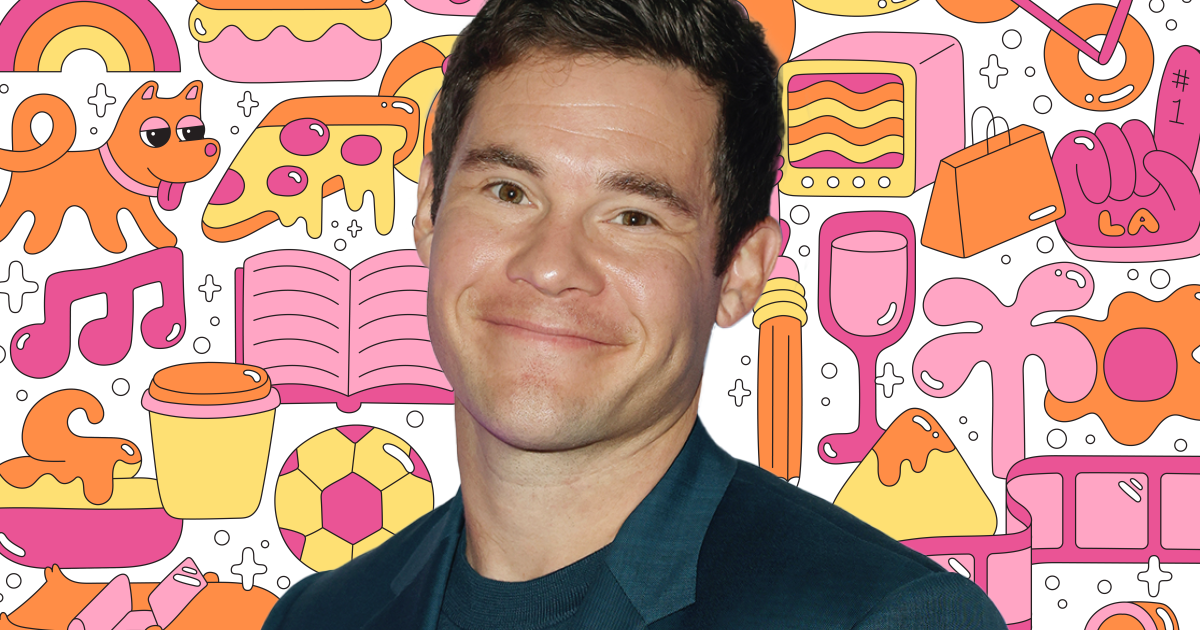

Dwayne Dionne, Alhambra Unified culinary specialist, in the district's central production kitchen.

(Carlin Stiehl / Los Angeles Times)

These ingredients can trigger “compulsive and addictive” children. [behavior] you see that so often with these types of products,” said Gearhardt, a food addiction expert who testified in favor of the bill.

The legislation will not ban all ultra-processed foods in schools, far from it.

Consider Alhambra Unified School District's Spicy Sriracha Tuna Roll. Sriracha could be considered an ultra-processed food, due in part to the presence of xanthan gum, a thickening agent, but it is not expected to be classified as such under the new law's category definition. Therefore, sushi is unlikely to be considered an ultra-processed food “of concern” or appear on the “restricted” list, experts said.

That would be good news for Patty Zaragoza, a food service worker in the Alhambra Unified School District's central kitchen. After packaging the last of the 350 sushi rolls, he said he never gets tired of them.

“Oh no, I love it!” she said.

The path to the law

For Gabriel, who was first elected in 2018, the Real Food, Healthy Kids Act marks the third food-related bill he has spearheaded.

In 2023, Gabriel authored the California Food Safety Act, which bans several food additives (including red dye #3) commonly found in soda, candy, and cereal. A year later, the assemblyman authored the California School Food Safety Act, which gained widespread attention because it bans Flamin' Hot Cheetos and other products that include certain synthetic food dyes in schools.

Gabriel said his extensive foray into food safety was an unexpected but personal turn. He has three children in elementary school. “A lot of the ways I see the world are through the lens of a parent,” he said.

A turning point: Gabriel learned that the harmful effects of certain synthetic food dyes can be amplified in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder.

ADHD “was something I struggled with as a kid,” he said, “and one of my kids is outgrowing it.”

Since Gabriel began drafting food-related legislation, the rise of the controversial Make America Healthy Again movement has highlighted issues surrounding dyes and other additives, and their potential links to a variety of health problems. But he said the new law emanates from “sound science,” adding: “We were doing a lot of this work before anyone had heard of MAHA.”

In a statement, Newsom said that “California has never waited for Washington or anyone else to lead on children's health.”

“We've been on the front lines for years, eliminating harmful additives and improving school nutrition,” he said. “This first-in-the-nation law builds on that work to ensure that all California students have access to delicious, healthy meals that help them thrive.”

Carol Chan serves beef and bean chili in Alhambra Unified's central production kitchen.

(Carlin Stiehl / Los Angeles Times)

Gabriel's bill garnered strong bipartisan support. But groups like the California Farm Bureau opposed it. Christopher Reardon, the office's vice president of policy advocacy, said in a statement that he “supports efforts to improve public health” but has questions about how the law will be implemented.

The Farm Bureau, he said, “will continue to work with its agricultural coalition to advocate for science-based food classification standards and ensure legislation supports farmers adapting to the changes.”

Inside the ban

So what will be banned?

It's complicated.

First, to be considered ultra-processed, foods must contain one of several non-natural substances spanning eight categories, including emulsifiers, stabilizers, flavor enhancers and flavoring agents. Next, it must have high amounts of saturated fat, sodium, or added sugar, or contain certain types of non-nutritive sweeteners.

Amanda Tejada carries a tray of chicken salad to store in the freezer in Alhambra Unified's central production kitchen.

(Carlin Stiehl / Los Angeles Times)

There are several exceptions. For example, a food that would be considered ultra-processed solely due to the inclusion of salt or certain natural seasonings cannot be classified as such. And other items cannot be considered ultra-processed, including raw produce.

Gabriel said he worked with the food and beverage industries to exempt certain items that made sense, such as minimally processed prepared foods, which include canned fruits and vegetables. There were conversations, he said, with representatives of the dairy industry, the protein industry and some who don't even serve food in schools, such as alcohol manufacturers.

“For a lot of them, it was about, 'In defining ultra-processed foods, how do you do that? How will that affect our product?'” he said.

It is not yet clear which foods will be considered ultra-processed foods of “concern” or which will be classified as “restricted.” The state Department of Public Health will create these food lists by 2028, so schools can prepare for the ban to go into effect.

The department must weigh a variety of factors, including whether the products carry a warning label in another jurisdiction about “adverse health consequences” and whether they contain a substance that, based “on authoritative, peer-reviewed scientific evidence,” is linked to “harms or adverse health consequences” such as cancer and cardiovascular disease.

“That's an investigation that should be done by California state scientists, not lawmakers,” said Scott Faber, senior vice president of government affairs at the nonprofit Environmental Working Group, who testified in support of the legislation.

Andrew Vasquez prepares corn and black bean salsa in the Alhambra Unified School District's central production kitchen.

(Carlin Stiehl / Los Angeles Times)

The law will hold sellers accountable, prohibiting them from selling banned items to California school districts starting in 2032. But it's not yet clear how districts will respond.

Los Angeles Unified, the state's largest school meal provider, declined to make its food services director available for an interview.

William Fong, director of food and nutrition services for Alhambra Unified, said his district already meets the USDA standards for school meals. Adhering to a new standard won't be too difficult, he said, even if changes are required.

“There's always a way to substitute… elements in a recipe,” Fong said. “And we have time.”

Gabriel believes vendors who supply food to school districts will comply with the law because California is a lucrative market for them. It could be as simple as changing one or two toppings on a pepperoni pizza or corn dog.

And, he noted, about one billion meals will be served in California schools this year.