Truly support

independent journalism

Our mission is to provide unbiased, fact-based reporting that holds the powerful to account and exposes the truth.

Whether it's $5 or $50, every contribution counts.

Support us in offering journalism without agenda.

Scientists and entrepreneurs are working to find ways to produce more cocoa or develop cocoa substitutes as climate change affects the forests where cocoa beans grow and puts chocolate at risk.

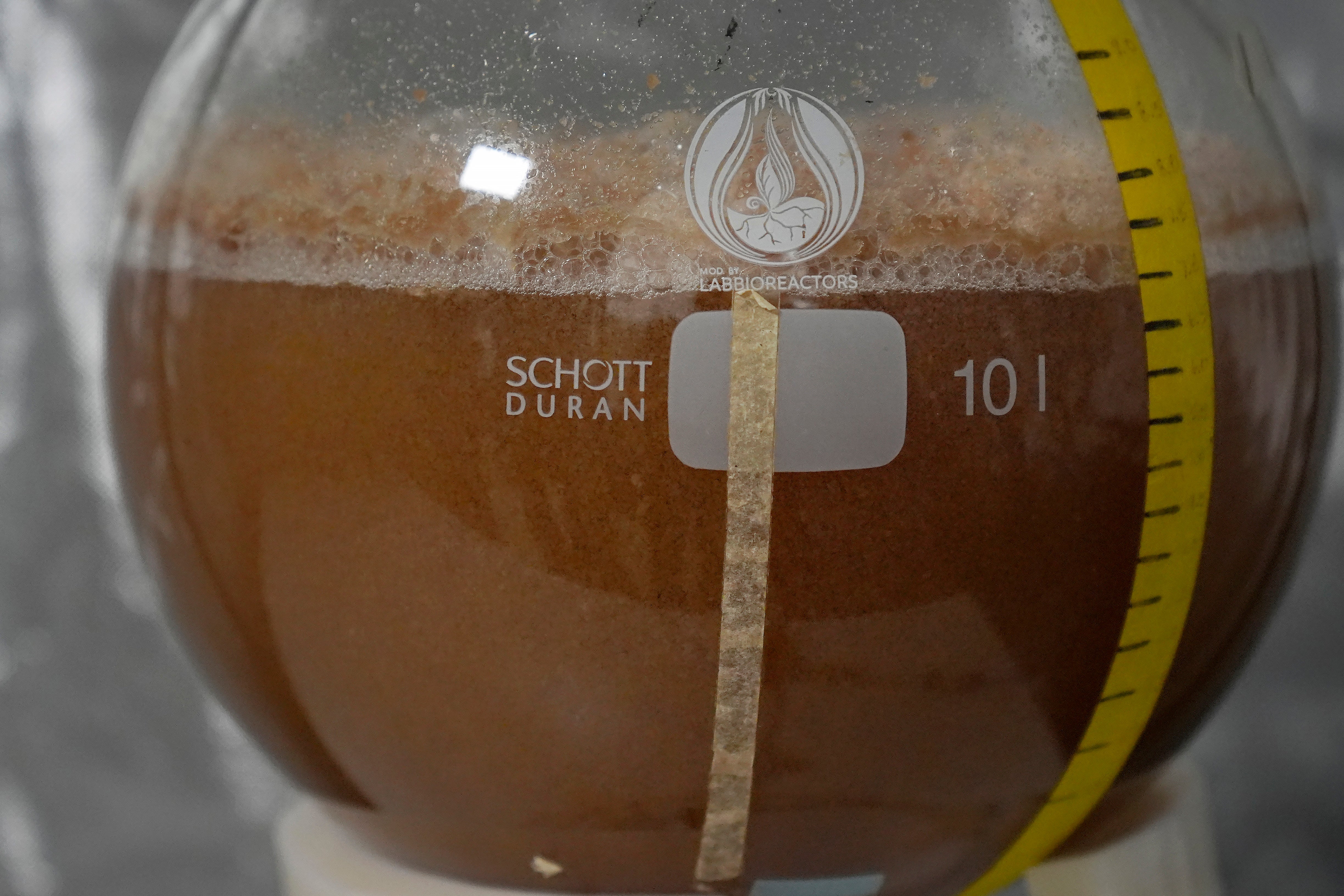

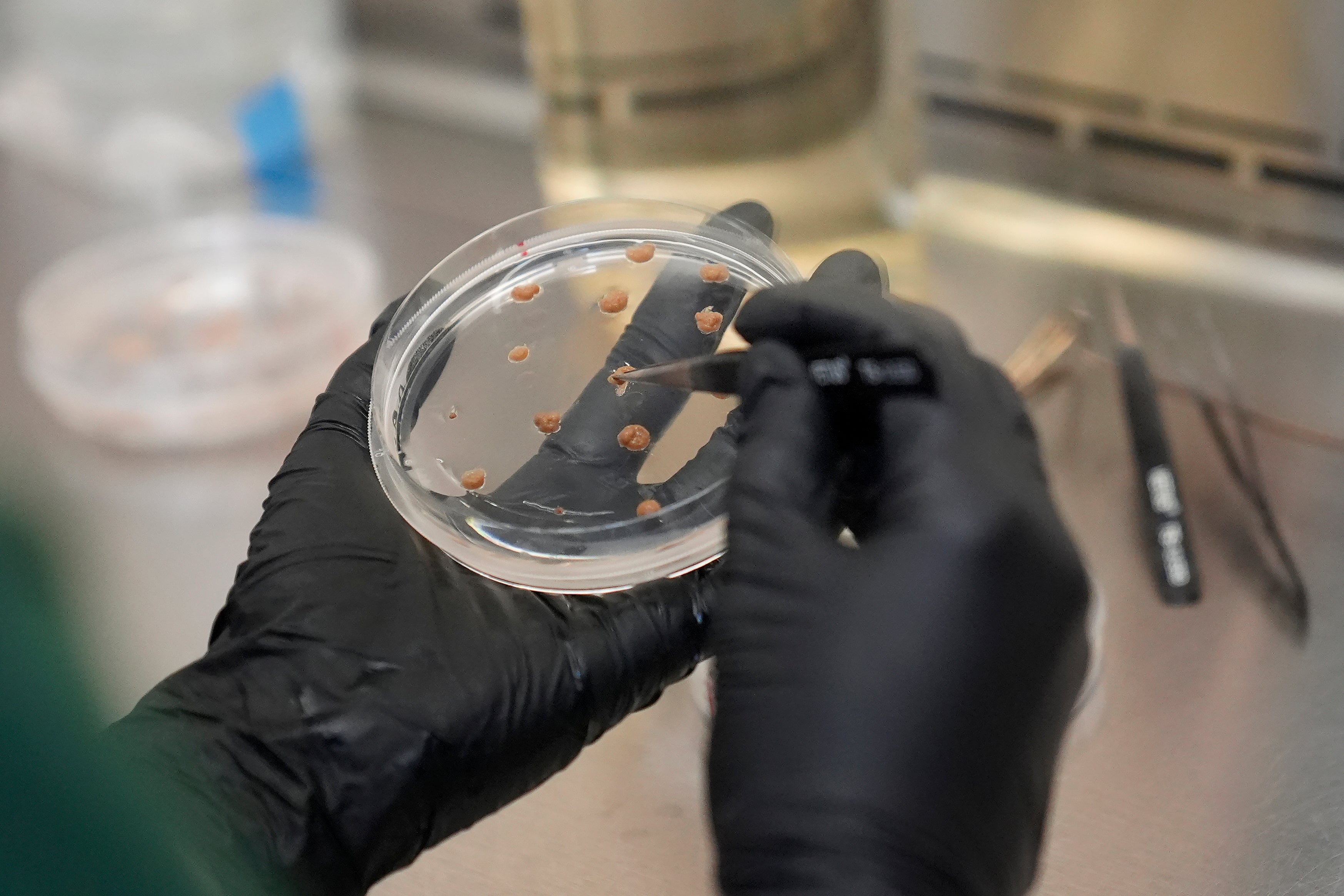

California Cultured, a plant cell culture company, is growing cacao from cell cultures at a facility in West Sacramento, California, and plans to begin selling its products next year. The company places the cells from cacao beans in a container of sugar water so they reproduce quickly and reach maturity within a week, rather than the six to eight months it takes for a traditional harvest, said Alan Perlstein, the company’s chief executive. The process is no longer as water- and labor-intensive.

“We see that demand for chocolate is vastly outstripping available supply,” Perlstein said. “There is really no other way for the world to significantly increase cocoa supply or maintain it at affordable levels without significant environmental degradation or some other significant cost.”

Cocoa trees grow about 20 degrees north and south of the equator in regions with warm weather and abundant rainfall, such as West Africa and South America. Climate change is expected to dry out the land due to the extra heat. So scientists, entrepreneurs and chocolate lovers are devising ways to grow cocoa and make the crop hardier and more resistant to pests, as well as to make chocolate-flavored alternatives to cocoa to meet demand.

The chocolate market is huge, with U.S. sales expected to top $25 billion by 2023, according to the National Confectioners Association. Many entrepreneurs are betting that demand will grow faster than cocoa supply. Companies are considering bolstering supply with cell-based cocoa or offering alternatives made from products ranging from oats to carob, which are roasted and flavored to produce a chocolatey flavor for chips or fillings.

The price of cocoa soared earlier this year due to demand and crop problems in West Africa caused by plant diseases and changes in the climate. The region produces most of the world's cocoa.

“All of this contributes to potential instability in supply, so it’s attractive for these lab-grown cocoa or cocoa substitute companies to think of ways to replace that ingredient we know as chocolate flavor,” said Carla D. Martin, executive director of the Fine Cocoa & Chocolate Institute and a professor of African and African American Studies at Harvard University.

Innovation is largely driven by demand for chocolate in the United States and Europe, Martin said. While three-quarters of the world's cocoa is grown in West and Central Africa, only 4% is consumed there, he said.

The push to produce cocoa indoors in the United States comes after other products, such as chicken meat, have already been grown in labs. It also comes at a time when supermarket shelves are filled with ever-evolving snack options, something developers of cocoa alternatives say shows people are willing to try what looks and tastes like a chocolate chip cookie, even if the chips contain a cocoa substitute.

They said they also hope to take advantage of growing consumer awareness about where their food comes from and what it takes to grow it, particularly the use of child labor in the cocoa industry.

Planet A Foods of Planegg, Germany, maintains that the taste of mass-market chocolate comes largely from the fermentation and roasting that goes into making it, not from the cocoa bean itself. The company’s founders tested ingredients ranging from olives to seaweed and settled on a mix of oats and sunflower seeds as the best-tasting chocolate alternative, said Jessica Karch, a company spokeswoman. They called it “ChoViva,” and it can be used in baked goods, she said.

“The idea is not to replace high-quality, 80% dark chocolate, but to really have many different products in the mass market,” Karch said.

But while some are looking to create alternative sources of cocoa and substitutes, others are trying to increase the supply of cocoa in places where it grows naturally. Mars, which makes M&Ms and Snickers, has a research center at the University of California, Davis, aimed at making cocoa plants more resilient, said Joanna Hwu, the company’s senior director of cocoa plant science. The center houses a living collection of cocoa trees so scientists can study what makes them disease-resistant to help farmers in producing countries and ensure a stable supply of beans.

“We see this as an opportunity and our responsibility,” Hwu said.

Efforts are also underway in Israel to expand the supply of cocoa. Celleste Bio is taking cells from cocoa seeds and growing them indoors to produce cocoa powder and cocoa butter, said co-founder Hanne Volpin. Within a few years, the company hopes to be able to produce cocoa independently of the impact of climate change and disease, an effort that has sparked the interest of Mondelez, the maker of Cadbury chocolate.

“We only have a small field, but eventually we will have a bioreactor farm,” Volpin said.

This is similar to an effort being undertaken by California Cultured, which plans to apply to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for permission to call its product chocolate — because, according to Perlstein, that's what it is.

It might end up being called brewery chocolate, or local chocolate, but chocolate nonetheless, he said, because it is genetically identical even though it does not come from a tree.

“We basically see that we are growing cocoa, just in a different way,” Perlstein said.

___

Taxin reported from Santa Ana, California.