He created a collection of some of the city's most influential restaurants and was dubbed “one of Los Angeles' most ubiquitous restaurateurs.”

Steven Arroyo, the prolific and flashy force behind Cobras & Matadors, Church & State, Escuela Taqueria, Malo, Boxer, Burger She Wrote, Cobra Lily, Potato Chips Deli and more, died at age 55 on Sunday due to medical complications from cancer treatment, one of his business partners confirmed.

In a career spanning more than three decades, Arroyo established himself as a curator not only of cutting-edge culinary trends and menus, but also of talent. While he was not a chef, he knew how to find it. Some of the city’s most prestigious chefs passed through Arroyo’s kitchens, including Walter Manzke of République, Neal Fraser of Redbird, Brooke Williamson of “Top Chef” and Playa Provisions and vegan authority Jared Simons.

The restaurateur had been battling cancer for some time. On a Friday night in April, in the dining room of his newly reopened restaurant Cobras & Matadors, he told the Los Angeles Times that just two weeks earlier, he had been unable to walk because of medication. But he said he was also a fighter, and that the process of opening a restaurant and being surrounded by all the familiarity and excitement was helping him regain his strength.

“It’s been good,” she said. “I think it’s healing to do things you love.”

Family was a constant for Arroyo. At Malo in Silver Lake, his mother inspired the restaurant’s menu and cooked in the kitchen several times a week. Over the years, his children were also present in his restaurants, sometimes working alongside him.

Whether overseeing the beef tacos with pickles at Malo and Escuela, which last week was named one of the 101 best tacos in Los Angelesor the garlic shrimp admired for decades at Cobras & Matadors, the restaurant owner had a hunch about what Los Angeles yearns for.

“Arroyo seems to have an uncanny intuition about what his audience wants to eat these days,” former Times food critic S. Irene Virbila wrote in 2001.

His brasserie Church & State, opened in 2008, not only attracted Manzke as a top chef, but was also one of the first restaurants to establish the Arts District, on the edge of downtown Los Angeles, as one of the city's most desirable places to eat and drink.

Arroyo's culinary career began early. He was born in 1969 in West Covina, the oldest of three children and the grandson of the supervisor of Bea's El Burrito in East LA. At 19, while selling coffee at the Santa Anita mall, he convinced the cappuccino machine repairman to hire him. He became a salesman for the company, and when one of his customers seemed unhappy, he bought his restaurant. Boxer was born.

“I always wanted to have my own small business, not necessarily a restaurant,” he later said. He told David Shaw of The Times“It could have been a hardware store, but when I started going to restaurants to sell them cappuccino machines, I thought, ‘Hey, I’m pretty good with people, I could excel at something like this. ’ I liked the idea of designing a room and having people come in and have fun.”

His first restaurant opened in 1995, with a bistro menu that blended California, Italian, French and Asian flavors, earning chef Neal Fraser widespread acclaim. “Boxer is the kind of restaurant we should be seeing more of and aren’t,” Michelle Huneven wrote in her review for the Times. It was a splashy launch that set the stage for Arroyo’s next concept, the wildly successful Spanish small-plates restaurant Cobras & Matadors.

When he debuted with Cobras & Matadors in 2001, Virbila wrote that Arroyo had “taken the bull by the horns” with food that was “more rustic and closer to authentic Spanish tapas than what any other restaurant is doing.”

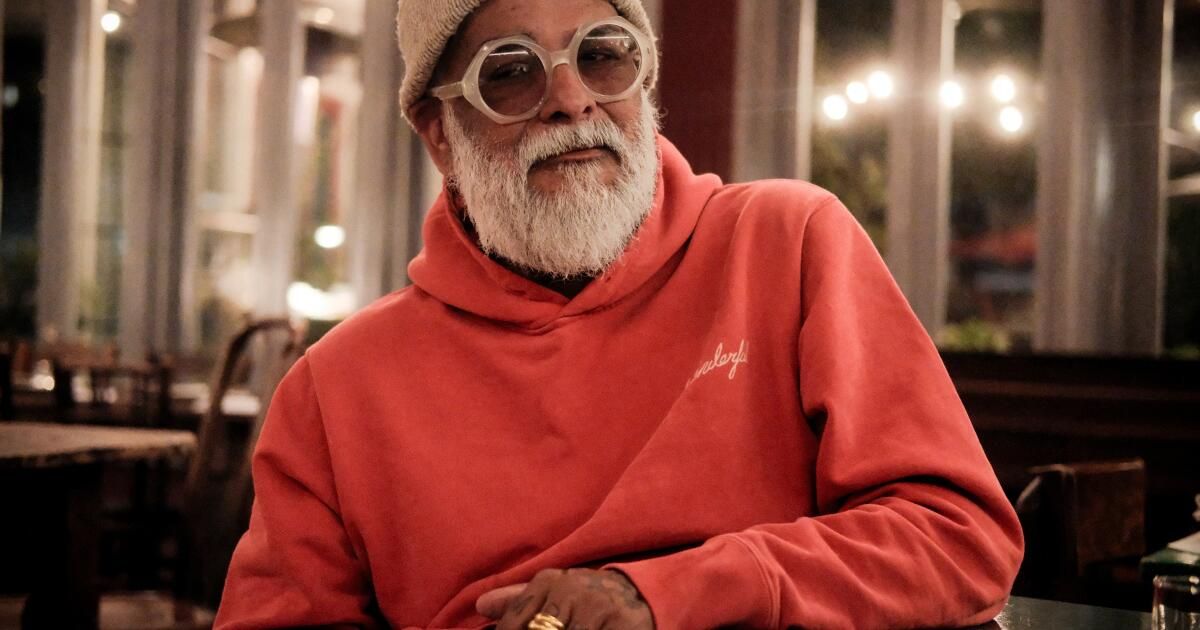

Steven Arroyo in 2004 at his restaurant Cobras & Matadors in Silver Lake.

(Ringo HW Chiu / For The Times)

Cobras & Matadors, one of Arroyo’s most recognizable restaurants, would expand, close, and open (sometimes reopening in new locations) for years, usually due to a popular but illegal BYOB policy, closing it in 2023 for what Arroyo thought would be the last time.

“He had been breaking, not even pushing, but violating, that law for years.” He told the Times this spring while sitting in the restaurant's latest iteration, this time on Melrose Avenue.

Earlier this year, he got another chance and reopened his beloved Spanish restaurant in the former Spartina space, complete with a full bar, just as he had always envisioned. He decorated the dining room with art and photos from his own collection, noting that it was a reflection of himself and, in some ways, an extension of his home to share with guests — a goal for all of his businesses, to feel comfortable and welcoming.

“My house is kind of empty because I just want to bring something from my home into this, because ultimately, that’s what it is; these three are my paintings, which I’m very proud of,” he had said in April, pointing to a trio of pieces on the wall. “And that one is by my friend Ashley.”

“I hope it will be a success,” he added about the reopening. “We are humbly trying to flap our wings for the third time and fly high. It is a difficult business, a humbling business.”

“Steven Arroyo is a master at creating the right atmosphere for his audience,” Virbila wrote in 2004“He is not interested in trends. His aesthetic is more modern and raw, with an almost perfect sense of the scene. He is allergic to gloss and evokes the urban and the dark in his interiors, usually with a theme that is barely sketched, only suggested.”

The nearby Escuela Taqueria de Arroyo, a Beverly Grove institution “dedicated to combining flavors with the corn tortilla,” also continues to feed the masses, as does the neighboring Smashburger destination She wrote a burger.

Arroyo is survived by his children Lola, Pele and Luca; his life partner, Aimee McNeilly; and several restaurants that continue to leave their mark on Los Angeles and its many ways of eating.