The Walt Disney Co. likes to resurrect a famous Walt Disney quote that says the empire “was started by a mouse.” But when it comes to Disneyland, its theme park that has become a Southern California institution, fans and history lovers crave specific details.

A new exhibit at the Walt Disney Family Museum in San Francisco aims to chart the beginnings and early evolution of the Anaheim resort, and begins with a trip Disney took with his friend, animator and fellow train enthusiast Ward Kimball to Chicago. The Midwestern city, as many know, is the birthplace of Disney, but in 1948 he and Kimball embarked on a vacation at that city's railroad fair.

At the festival, they enjoyed not only locomotives, but also an Abraham Lincoln impersonator and large grounds that featured small recreations of a frontier town and a Native American village, elements that would eventually make their way to Disneyland. And while in Chicago, the duo stopped at what is now the Griffin Museum of Science and Industry, home to a recreation of a turn-of-the-century city street.

Early 1950s concept art for Main Street at Disneyland, USA, by Harper Goff. The work is on display in a new exhibit at the Walt Disney Family Museum in San Francisco.

(Walt Disney Family Foundation Collection / Harper Goff Collection / Disney)

By the time the trip concluded, Disney's vision for Disneyland had begun to take shape. Within days of returning to Los Angeles, Disney had written a memo outlining his ideas that would eventually appear at Disneyland, including a train, a park, and a variety of vintage shops.

So maybe it's more accurate to say that, with Disneyland, it all started with a vacation to Chicago.

The Walt Disney Family Museum in San Francisco is dedicated to preserving the history and legacy of Walt Disney, detailing his roots in the Midwest, his achievements in animation, and the development of Disneyland.

(Walt Disney Family Museum)

The museum's exhibit, “The Happiest Place on Earth: The Story of Disneyland,” is based on a similarly titled book by animation producer Don Hahn and theme park designer-turned-historian Christopher Merritt. Consider the museum's display a sort of greatest-hits companion to the coffee table tomb, which is an indispensable look at Disneyland history, a work that compiles never-before-seen conceptual art and shines a spotlight on many of the park's lesser-known designers.

The exhibit and book coincide with Disneyland's 70th anniversary. The first adds to and complements the museum's mission of preserving Walt Disney's legacy, showing the park's patriarch as a kind of conductor who built Disneyland with the help of creatives from all over Hollywood.

-

Share via

Spread across two lower-level galleries, and also including a short film by Hahn, one that places heavy emphasis on that Chicago tour, the exhibition, which runs through May, unfolds as a kind of walk in the park. Some portions are dedicated to Disneyland's past and present lands (the exhibit includes the defunct “Indian Village,” an aspect of Frontierland that flourished in the 1950s and '60s), but rather than attempting to capture the park as a whole, the museum focuses on rarely exhibited conceptual art from various Disneyland artisans.

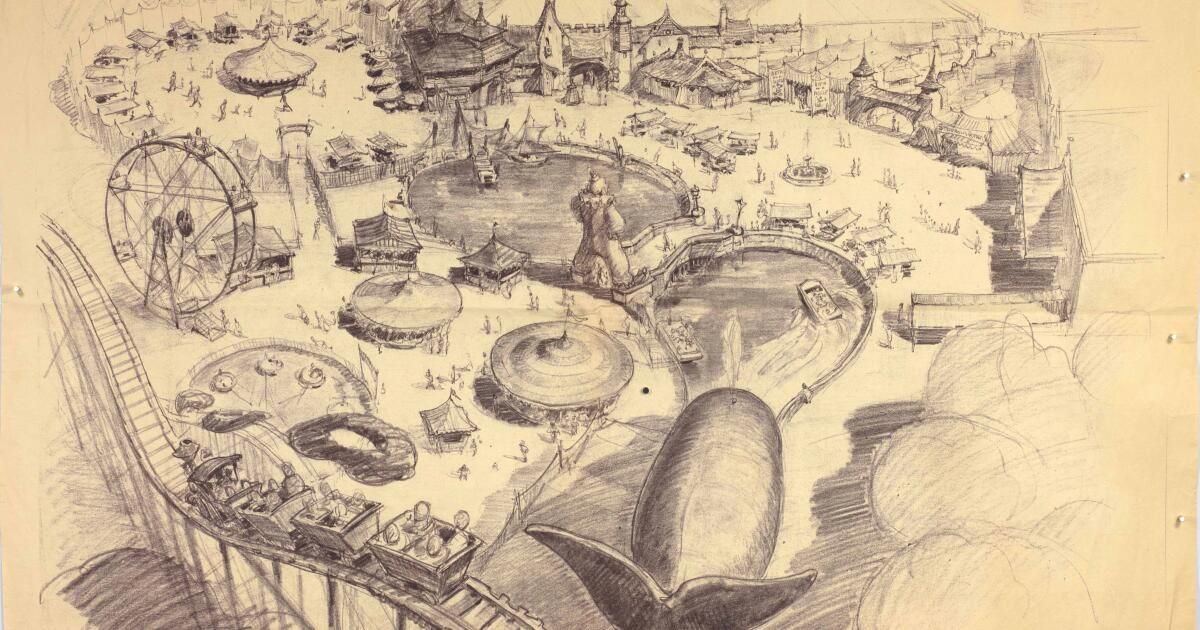

The centerpiece of the main gallery is a rarely resurrected pencil drawing of Fantasyland by Bruce Bushman, who created pre-groundbreaking concept art inspired by Marvin Davis' master plans. You'll see a small roller coaster, a mini Ferris wheel, and a circus area, complete with a large clown statue that would tower over guests. It is markedly different from both the land's Renaissance Faire-inspired beginnings and its European village appearance today, but it is also emblematic of how Disneyland did not emerge fully formed and was gradually iterated before its opening in July 1955.

More Bushman art is displayed elsewhere, notably his Pirates of the Caribbean drawing as a wax museum. In the mid-1950s, before it was decided that the attraction would be a boat ride, it was conceived as a tour experience complete with indoor shops and a large battle stage. Hahn, who served as co-curator of the exhibit, in a tour of the museum's artifacts notes that Bushman was working on “The Mickey Mouse Club” around the time he was also coming up with plans for Disneyland.

Hollywood designer Renié Conley's Disneyland costume designs are on display as part of a new exhibit at the Walt Disney Family Museum.

(Frank Anzalone / Walt Disney Family Museum.)

“There are remnants of what became the attraction,” Hahn says, pointing to depictions on the map of tunnels and sandy areas with hidden loot. “There are battles and you have to cross a rickety bridge over a swamp, probably with alligators. This drawing, in particular, is really special, seeing the original white pencil drawing. Again, Bruce Bushman, here's a guy who does 'Mickey Mouse Club' sets, but he also does these deep things.”

Previously, the exhibition pays special attention to prominent Southern California landscape architect Ruth Shellhorn. She was hired just four months before the park opened, but is credited with perfecting pedestrian flow and designing landscaping that facilitated transitions between Disneyland's central hub and its grounds.

“We built the park as we went,” reads a Shellhorn quote used in the book and exhibit and taken from the Shellhorn archives at the UCLA Library. “I doubt that this procedure could have been followed successfully in any other project on Earth; but this was Disneyland, a kind of Fairyland, and Walt's belief that the impossible was a simple order of the day so instilled this spirit in everyone that they never stopped to think that it couldn't be done.”

Also on display is costume designer Renié Conley, who worked on films such as “The Great Fisherman” and “Cleopatra.” His work is shown for the front areas of the Main Street park, and it is Victorian, stately and slightly fanciful. A yellow and white dress, for example, gives a sense of movement and is perfect for both a tea party and a dance.

A key component of the book and exhibit, Hahn says, was the desire to focus on some of the important contributors to Disneyland who may not be household names to fans of the park. “Let's tell the human story of this,” Hahn says. “All the crazy people who worked on this in an incredibly short period of time. That attracted me.”

Harper Goff, Bill Evans, Dick Irvine, Walt Disney, Ruth Shellhorn and Joe Fowler examine plans for Disneyland in April 1955, just months before the park opened.

(Ruth Patricia Shellhorn Papers, UCLA/Disney Library Special Collections)

Also on display are artwork for abandoned concepts, such as a never-built Chinese restaurant with a robotic host that was conceived for Main Street, as well as alternative visions for the introductory lot. On display are some of the early designs for It's a Small World by beloved animator-turned-theme park designer Marc Davis. This was before it was decided to create the attraction in the look and tone of artist Mary Blair, and Davis's little concepts had a more refined look: a cartoon London, for example, rather than a playground.

Rare art by the late Walt Disney image maker Rolly Crump for the never-built Museum of the Weird is on display as part of a new exhibit at the Walt Disney Family Museum.

(Photo by Drew Altizer/Walt Disney Family Museum)

Also rare: a small model of a hobo carriage by Rolly Crump, who worked on Haunted Mansion, Enchanted Tiki Room and It's a Small World, among other projects. Crump is responsible, for example, for the whimsical facade of It's a Small World. The carriage, with mystical designs inspired by divination, was created for the never-built Museum of the Weird, which would have been located next to the Haunted Mansion. Crump's son Chris says it may be one of the only surviving designs from that project.

As a whole, the exhibition shows not only the beginnings of Disneyland, but also how the park became an ever-evolving art project.

“It's important,” Hahn says, when asked why Disneyland has not only endured, but remains a pilgrimage for so many people. Theme parks allow us to explore stories and fairy tales in a multidimensional space: an escape, yes, but also a reflection of the narratives that define a culture. And, Hahn adds, it is a source of rejuvenation. “It's not just kid stuff,” he says. “It's important for our mental health.”

Because when you go to Dinseyland, Hahn says, “you don't think about the gas bill or your kids' education or how you can't afford to live paycheck to paycheck. It's not cheap. It's not a cheap day. But we still go because our hope is to get something there that we can't get in everyday life. To me, that's human regeneration, the ability to be inspired and get out of our heads for a while.”