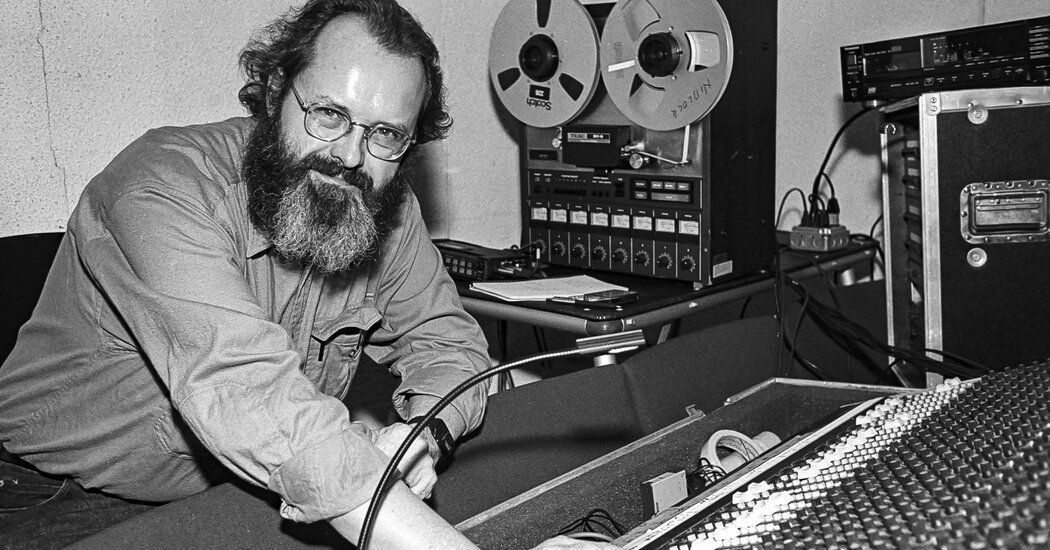

Phill Niblock, an influential New York composer and film and video artist who broke new sonic ground with hauntingly minimalist works that incorporate drones, microtones, and instruments as diverse as bagpipes and hurdy-gurdies, often accompanied by his equally minimalist moving images, He died Monday in Manhattan. He was 90 years old.

His partner, Katherine Liberovskaya, said he died in hospital of heart failure after years of heart procedures.

Mr. Niblock had no formal musical training. However, he came to be acclaimed as a leading figure in the world of experimental music, not only as an artist but also, beginning in the 1970s, as a director, along with choreographer Elaine Summers, of Experimental Intermedia, a foundation for dance. , avant-garde music and other media. He served as sole director of the foundation from 1985 until his death, and was also curator of the foundation's record label, XI.

His loft on Center Street in Lower Manhattan served as a performance space for the foundation. He was also a social nexus for boundary-pushing musicians and composers such as John Cage, Arthur Russell, David Behrman and Sonic Youth's Thurston Moore.

In an Instagram post on Tuesday, Moore wrote that Niblock's work summoned a “collective consciousness that gave him his own genuine commitment to both listener and performer.”

Mr. Niblock's music was marked by densely layered sound textures consisting of tones, close in pitch to each other, that made only very small movements over prolonged periods. “To me, minimalism is about removing things and looking at a very small segment, getting rid of the typical melody, rhythm and harmonic progressions,” Niblock said in an interview with Frieze magazine last summer. He added that his pieces “don't really 'develop,' as that word is used in music.”

The films and videos that typically accompanied his music were also conspicuously absent of convention, eschewing snappy editing and narrative arcs. “In reality, the play is really stripped of most of the material that makes up a film,” she said.

Ms. Niblock's best-known work was the piece “The Working People's Movement,” which she first performed in 1973 and continued to update it over the years and perform it around the world. It consisted of hypnotic drone music, accompanied on multiple screens by her meditative (and plotless) films, made around the world, about fishermen, farmworkers, and other workers.

For the initiated, the effect of his work could be fascinating. “His performances were powerful, long-lasting ritual experiences that take over the senses,” David Watson, a guitarist and bagpiper who performed with Niblock for decades, wrote in an email. “His uncompromising approach (no melody, harmony or rhythm, just the interplay of tones and the release of all the energy they contain) changed the way we saw what is possible with performance.”

Phillip Earl Niblock was born on October 2, 1933 in Anderson, Indiana, the only child of Herbert Niblock, an engineer in the automobile industry, and Thelma (Smith) Niblock, who ran the household.

After receiving a bachelor's degree in economics from Indiana University, he served a stint in the Army; After his discharge in 1958, he headed east. “I was a jazz fan and I thought if I was going to settle somewhere, why not come to New York?” he said in a 2007 interview with Paris Transatlantic, an online magazine dedicated to new music.

He began his creative career in the city as a photographer, photographing Duke Ellington and other jazz artists, and later worked as a cinematographer filming the work of avant-garde choreographers such as Ms. Summers. At that time, he had no thoughts of pursuing a musical career.

“I was never really interested in being a musician,” he said. “I took piano lessons for about six weeks and my father thought he didn't practice enough, so he fired the piano teacher.” He never learned to play an instrument; At concerts he relied on tape machines and, eventually, laptop computers to play prerecorded parts while carefully positioning speakers and adjusting sound levels to accentuate the acoustics of the space.

But in 1961, he saw a performance of a piece by experimental composer Morton Feldman, which opened a new world to him. “It was an incredible revelation to be able to have a piece without rhythm or melody, and with those long tones,” he told Paris Transatlantic. “It really was kind of a permission to make music in a similar way.”

While working in a decidedly non-commercial field, Niblock also earned a salary for decades as a professor at the College of Staten Island, part of the City University of New York, teaching photography, film and, later, video. Following his retirement in 1995, he toured for up to eight months a year until his final months.

His work remained invariably challenging and often presented at aggressive volume. At a performance at Union Chapel, an imposing church and performance venue in London, he almost literally shook the rafters.

“During the concert I felt this kind of rain,” he told Paris Transatlantic. “I felt my hair and it was crumbly. It was the plaster of the dome, seeping through the air. “It must have been more than 120 decibels.”

In addition to Ms. Liberovskaya, Mr. Niblock is survived by a son, Jasper.

Even for the musicians who perform it, Niblock's music could have a lasting effect. “After a while playing Niblock pieces, I'm going back to playing normal music,” Watson said. “If it has more than three notes, I think, 'What's all this rococo nonsense?'”