Cognitive dissonance, SoCal style: The calendar says it's November, but the sky swears it's April, maybe even July.

Is Thanksgiving. And for more than a hundred years, pilgrims from the East and Midwest to this Pacific coast have sometimes felt a little bewildered about how to carry out a holiday built 400 years ago around the original Atlantic Coast pilgrims.

“Here in the West, no one gets very excited about Thanksgiving,” lamented Times columnist Harry Carr when referring to the Christmas crisis of 1923. “You have to be somewhere in the footsteps of the Pilgrim Fathers.” to understand the meaning of Thanksgiving Day. “

But somehow we managed. We suffer a vacation without snow and without puritans surfing, rock climbing, skiing, when the smell of smoke is not necessarily that of burning turkey, but can be that of forest fires.

In 1957, Thanksgiving marked hunting season for the West Hills Hunt Club (the horseback, top hat, and riding coat kind of hunting) with the “Blessing of the Hounds.”

The uniquely American version of Thanksgiving is governed by more rigid rules than those of Christmas. Christmas celebrations are global and elastic; Thanksgiving is a day of fixed, ritualized practices, no matter where in the United States it is celebrated.

Newsletter

Get the latest from Patt Morrison

Los Angeles is a complex place. Luckily, there is someone who can provide context, history and culture.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

There's a lovely movie from 2000 called “What's cooking?” It is set in Los Angeles, with an excellent cast playing four families (black, Vietnamese, Jewish and Latino) who bring their own varied flavors of life and food to the Thanksgiving table, trying, in the midst of the panics family and culinary catastrophes, Achieve the impossible: a perfect Thanksgiving. (The combination of scenes of four families' potato-mashing techniques is classic.)

For a long time, in Los Angeles as elsewhere, Thanksgiving was primarily a religious holiday, a council of captain Puritan hat to the tenacious Calvinism of the Mayflower crowd. The Times routinely printed, at astonishing length, Thanksgiving sermons by well-known local pastors.

That, at least, felt like home to the hundreds of thousands of Protestant Middle Americans who immigrated to Los Angeles and, in the land of the Spanish missions, built churches with New England-style white clapboard steeples.

In 1896, The Times gave its city a pat on the back: “It was wise foresight that first ordered church service to precede Turkey on Thanksgiving Day. Grace before the meat is particularly appropriate on this particular holiday… before dinner, [the ordinary American] He may be devout; after dinner, he is in a coma.”

In 1899, at the cusp of the 20th century, The Times cleared its throat to announce a new secular civic celebration. “This year Thanksgiving will be celebrated in Los Angeles like never before. … Until now, Thanksgiving has been one of the quiet holidays of the year, dedicated to church services and, of course, football.” But now “there will be a military and civic parade, patriotic exercises on the bicycle track, a football match, golf, a banquet, a sacred concert and many other sources of fun and pleasure.”

California Thanksgiving celebrations and reenactments celebrated Massachusetts Native Americans, but passed quickly Local Native Americans who had been all but erased. of the city's demographics. In the 1899 Thanksgiving parade, a group of white pioneers marched; was named, without irony, “Native Sons of the Golden West.”

A turkey asks a fair question: “What should I be grateful for?” — on this vintage postcard from the Patt Morrison collection.

On a postmarked 1923 card from Morrison's collection, a correspondent asks his brother, who was possibly at the school, given the St. Olaf College mailing address, “Do you want turkey?”

Thirty years later, Thanksgiving in Los Angeles was downright secular and uniquely ours: sports, games, picnics on the beacha “fairyland” parade downtown, the delight of warm weather rolls over the hills.

The studios gave everyone the day off. In 1940, The Times assiduously documented the Christmas activities of movie stars: Broderick Crawford leaving for honeymoon in Honolulu; housemates Franchot Ringtone and Meredith Burgess organize a dinner for friends; Errol Flynn lead to Palm Springs for tennis; Donald Crisp and George Brent in the water on their respective yachts; Barbara Stanwyck and Robert Taylor play golf with Jack Benny and his wife, Mary Livingston; and the Bela Lugosis We're going to dinner at his mother's house. (That's her straight line, amateur comics: do it.)

On Thanksgiving Day 1929, a month after Wall Street (as Variety headlined it) laid an egg, The Times noted in many print columns that free food was being served to the “unfortunate” at the Salvation Army, the Midnight Mission and several churches. Years before, food donations were made in poor neighborhoods, and veterans at the Former Soldiers' Home in Sawtelle (now VA land in Westwood) were fed abundantly.

The county jail's Thanksgiving menu made headlines, probably because of who would eat it.

Sweet potatoes, fruit jelly, and roast pork (not turkey) would be served to all inmates, from the humblest pickpocket to what constituted the celebrity wing and its residents:

- Alexander Pantages, the millionaire theater magnate convicted of raping a 17-year-old dancer.

- Asa Keyes, former Los Angeles County district attorney, who sent men to the cell he now occupied; he was convicted of accepting a bribe.

- Leo (Pat) Kelley, back in town from San Quentin's death row, to be re-sentenced on the lesser charge of involuntary manslaughter, for murdering his older, married “cougar” girlfriend. Kelley said he had gained 25 pounds at San Quentin, and probably gained a few more at Thanksgiving.

A vintage postcard from Patt Morrison's collection is addressed to “Dear Little Raymond” and bears a postmark of 1912. It was mailed from Florida to Brattleboro, Vermont.

That episode is a clear contender to win the sweepstakes for the most Thanksgiving incidents in Southern California. But if my vote were the only one, the palm would have to go to this one, from Thanksgiving Day 2000.

Wendy P. McCawa woman we describe as the “libertarian-environmental billionaire,” bought the venerable Saint Barbara News-Press in 2000, and just last July, declared the newspaper bankrupt and closed it.

For Thanksgiving that first year, an editorial urged locals to donate generously to a local food bank, but with an asterisk: no turkey, please. “We cannot, in good conscience, recommend the continuation of a tradition that involves the death of an unwilling participant…donate a turkey if you wish, but you can also donate all the other delicacies associated with a holiday meal. “Beans and rice are a good protein substitute for turkey.”

Not all Santa Barbara residents welcomed the suggestion, and to show your discontentdonated 700 more dead turkeys than the food bank had requested.

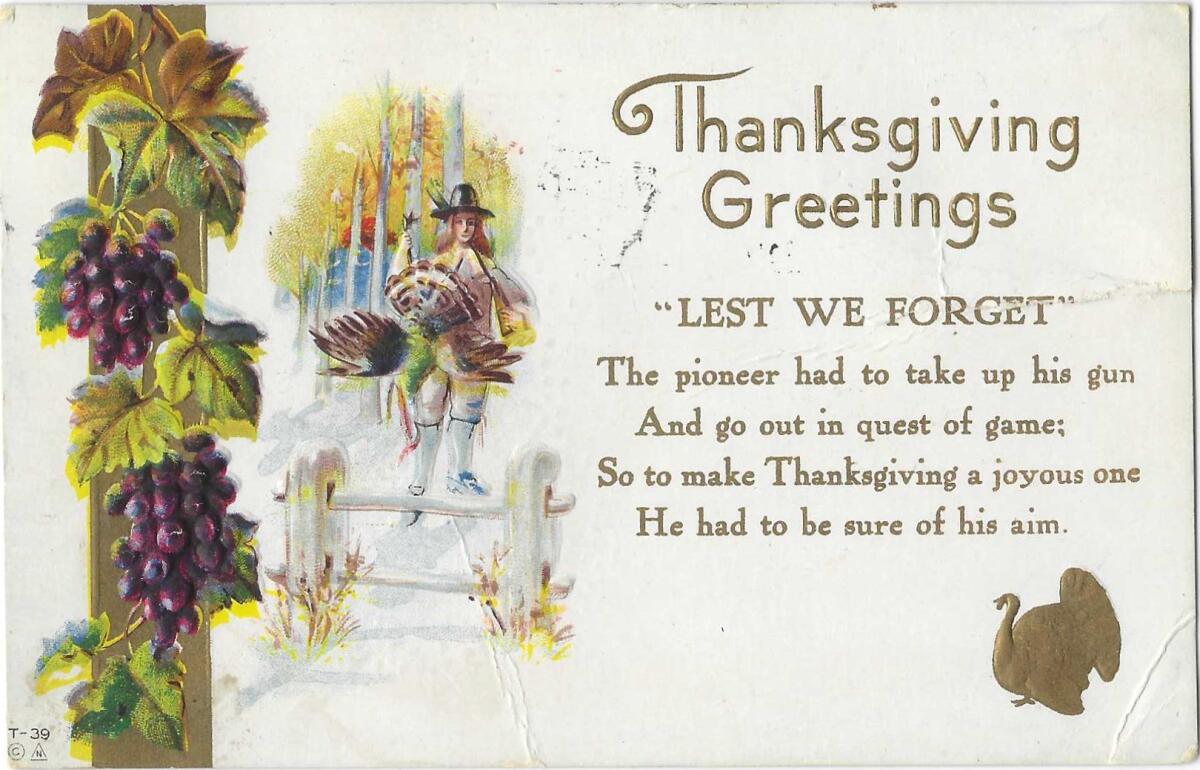

Treat your holiday guests to this Thanksgiving verse, found on a postmarked 1915 postcard from the collection of Patt Morrison.

Explaining Los Angeles with Patt Morrison

Los Angeles is a complex place. In this weekly article, Patt Morrison explains how it works, its history and its culture.