Truly support

independent journalism

Our mission is to provide unbiased, fact-based reporting that holds the powerful to account and exposes the truth.

Whether it's $5 or $50, every contribution counts.

Support us in offering journalism without agenda.

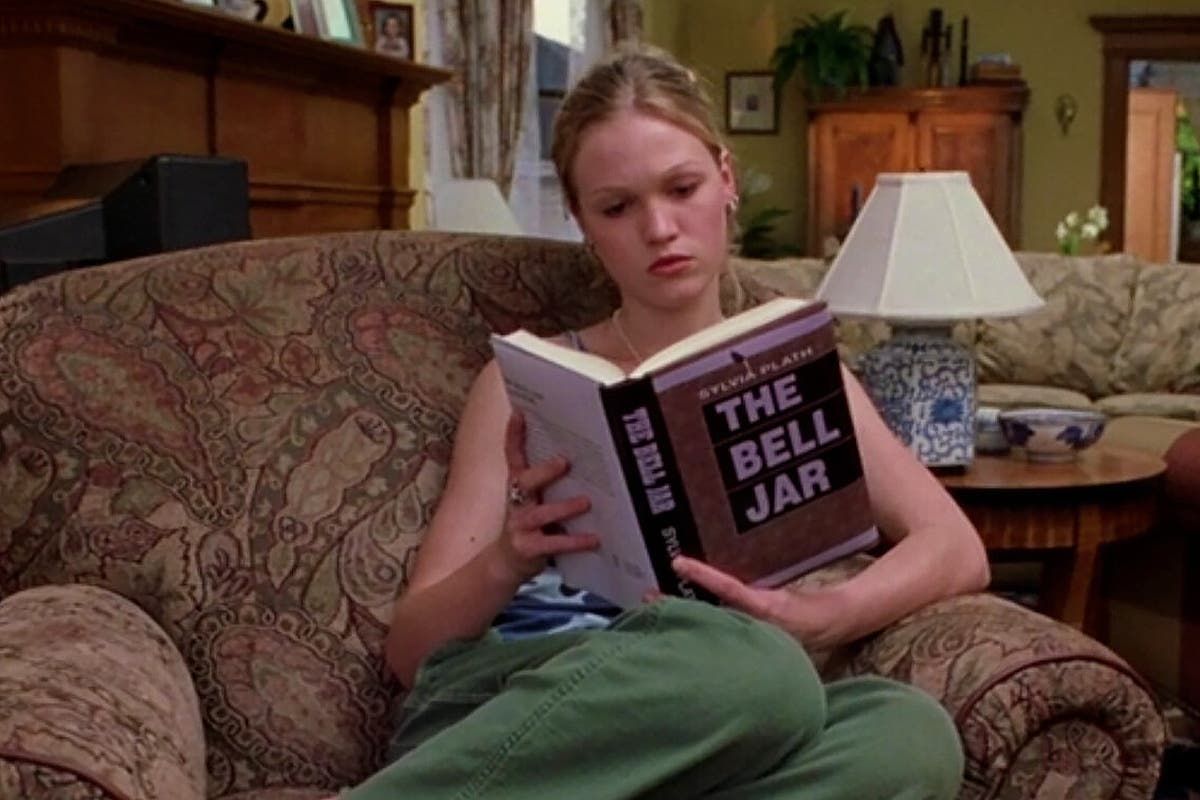

IThink of any “sad girl” in a movie. You know the one: She wears baggy jeans and band T-shirts, slams doors and sits alone in dining rooms. And she’s almost always reading. The Bell Jar by Sylvia Plath, a semi-autobiographical text that has become the ultimate signifier that a female character is problematic, tragic or tormented.

There is 10 things i hate about youin which Julia Stiles' sardonic character Kat examines the pages of Plath and the cult eighties comedy, Heatherswhen Heather Chandler is found dead with a copy next to her. It is even referenced in Family man and The Simpsons, with Lisa Simpson reading it. And it's on Netflix Sex education, Courtesy of the temperamental Maeve Wiley.

Fast forward to today and we now officially have the so-called “sad girl” literary trend circulating Bell jar-heart-shaped fulcrum. In the wake of the #MeToo movement, the publishing world has been turning its attention to books in which young women deal with some form of trauma, usually with covers that show them falling face-first into walls or cakes. These include Cleopatra and Frankenstein by Coco Mellors, which explores alcoholism, loneliness and sex work, Pain and joy by Meg Mason, which deals with mental health, Parts of a child by Eliza Clark – a young woman takes pornographic photos of men – and all by Sally Rooney. It is not a template that fits everyone. And yet, last summer there was even a book published entitled Sad girl novel by Pip Finkemeyer.

On TikTok, “sad girl” has become a genre unto itself. A quick search for the term will reveal over 47 million results. Often, these are short videos that showcase the books with some sort of lingering orchestral music and a slightly creepy voiceover talking to you about the meaning of life and love and everything in between. As for what actually defines these titles (if it’s not TikTok, that is) it could be anything from a female protagonist with mental illness to one going through a bad breakup. The term itself is controversial; no one in the literary world can decide for sure whether it’s a good or bad label, and some say it’s patronizing or even potentially quite dangerous.

“I don’t want anyone to overdose on Ambien from reading my book,” said Ottessa Moshfegh, a staunch defender of the genre. “This is satire, this is not real.” Others, like Finkemeyer, have embraced the popularity of the genre, saying: The Guardian“I'm trying to balance the metaphorical nature and ironic references with my desire to give readers a serious, real part of myself with real emotional depth.”

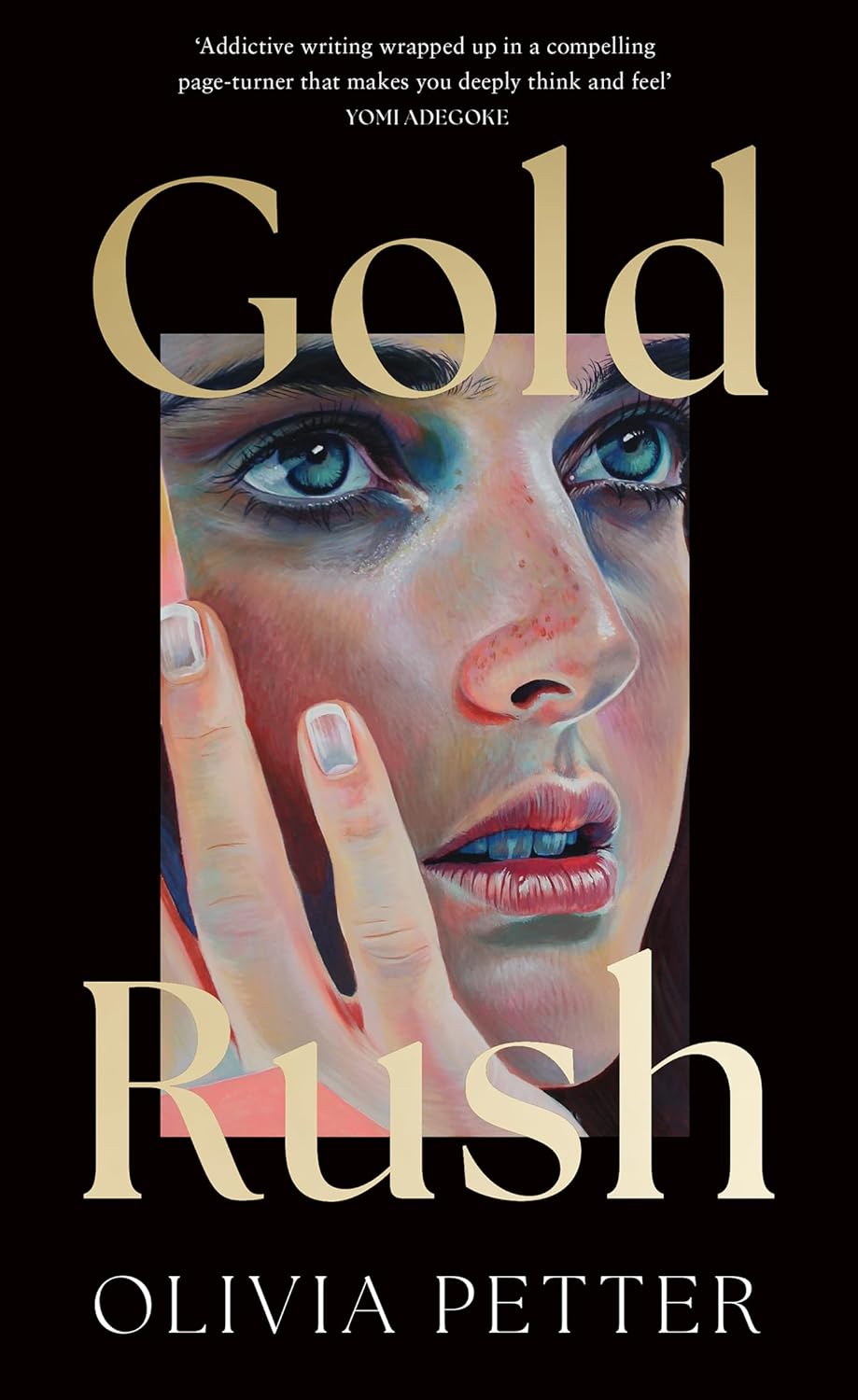

But what does the homogenization of so many complex stories featuring women say about the female experience? That anything too complicated or too nuanced is beyond our intellectual capabilities? That the range of female emotions is simply too wide for mainstream culture? Or does it say something more insidious about how women are judged and oppressed for being themselves? God forbid we show rage, passion, or fear; it’s so much easier to just be “sad.” I was aware of all this when I started writing my own novel. Golden fevera process that began as this trend spread around me. Told from the perspective of Rose, a twenty-something, the book examines how a chance encounter with a charismatic pop star turns into something more sinister.

I just hope that readers will see my book as more than just “another sad chick-lit novel.” Because yes, there are “sad” elements in it, but there are also lighter parts that satirize the absurdities of fame and the egos that come with it.

The bulk of the book focuses on the aftermath of one drunken night, examining the power dynamics between men and women as well as the nuances surrounding consent and celebrity culture. It’s a complex and deeply personal story. And I was nervous about having to take something I care so deeply about and boil it down to a single, blanket term. Don’t get me wrong, I love all of the authors I’ve mentioned and it would be a privilege to have my work discussed alongside theirs. But if someone called my book a “sad girl” novel, I’d feel more conflicted. And not just because of the simplifying aspect. First, there’s the basic sexism of it all (have you ever heard of a “sad boy” book?) which connects to a larger, deeply ingrained narrative I’ve noticed percolating around female novelists.

Second, there is the assumption that women’s creative work must be autobiographical – something I’ve been asked about countless times, feeling the sting of my imagination increasingly undermined, and undermining our imaginations. Then there is infantilisation: girl, not woman. This is of course an increasingly absurd idea endemic to the internet: hot girl summer, tomato girl summer, wild girl summer, sexy girl walks, girl dinners, girl maths… The tyranny of it all is becoming exhausting. But it seems particularly insidious in a literary context, because it is once again a way of crushing our imaginative authority and belittling our credibility, both as artists and as adults.

Finally, there’s the word “sad,” which seems pejorative. “Your sad little book,” etc. Why not “tragic”? Or “melancholic”? Or literally any other legitimate adjective people use to describe a story, ideally one that hasn’t been plucked from the lexicon of a four-year-old? Why do people have such a hard time taking female novelists seriously? It’s something we all grapple with, too, regardless of how successful we’ve become; even Rooney, the most successful novelist of her generation, has spoken of how uncomfortable she is with readers who align their own lives with her books, in which the female protagonists are often pensive, esoteric loners.

I can only hope that readers see Golden fever as more than just “another sad chick-lit novel.” Because yes, there are “sad” elements in it, but there are also lighter parts that satirize the absurdities of fame and the egos that come with it. It examines the modern media landscape, classism, and nepotism. It also examines the nuances of sexual trauma and emotional abuse, topics that I feel are not discussed enough in pop culture and surely deserve a more detailed description than “sad.” Like all of the titles I’ve mentioned, Golden fever is fundamentally a book about the female experience. And rather than trying to lump it together with other books in neat little bundles because that happens to be more Instagrammable, perhaps it's better to read these books and categorize them ourselves, with or without a hashtag.

Olivia Petter's 'Gold Rush' to be published by 4th Estate on July 18