Joseph Cornell, who died in 1972 at the age of 69, belongs to the tradition of the home artist. A gray whisperer of a man, he eschewed the thrills of travel in favor of a tea-filled life at his home on Utopia Parkway in Queens. His medium was the Box, that is, the Victorian shadow box, and he spent his days in his basement workshop, assembling cork balls, paper cutouts of birds, and other thrift store materials into incredibly beautiful arrangements. poetics that owed something to French surrealism. .

Among the cities he never visited was Washington, DC. So one wonders what he would make of the news that the National Gallery of Art has just acquired a veritable truckload of his work: some 20 boxes and seven collages from his entire career. The gift comes from Robert and Aimee Lehrman, Washington collectors.

Robert Lehrman, trustee of the Hirshhorn Museum and grandson of the co-founder of Giant Foods, a supermarket chain, has lectured widely on Cornell and purchased his first piece in the early 1980s. “It was a white pigeon box that had a childhood mystery,” he said. “I like that his work is both very simple and very complex.”

In some ways, it's hard to imagine Cornell's intimate boxes nestled comfortably in the marble-lined hallways of the National Gallery. The modest scale of her work, its reek of a romantic past, belies it with the epic proportions and official air of IM Pei's east wing, whose atrium alone is likely to increase a visitor's daily footfall.

On the other hand, Cornell seems perfect for the nation's capital because its history is archetypically American. He was stubborn, moody, and consumed by the beauty of common objects; He persisted with his art in the face of enormous loneliness. Living with his mother and his disabled brother, he was inspired by the work of other artists and dedicated his paintings to figures ranging from composer Franz Schubert to poet Emily Dickinson and television actress Patty Duke.

The Lehrmans' gift, which comprises about half of their holdings at Cornell, “is important, important, important,” said Harry Cooper, senior curator and director of modern and contemporary art at the National Gallery of Art. Although the museum has received much larger bequests, the donation, he said, is unique because it is directed to a single artist and presents his work with unusual depth.

“I would say that 20 Cornell boxes and seven collages put us alongside the Art Institute as one of the two major collections of one of the great artists of the 20th century,” Cooper said. “That doesn't happen every day.” The collection he mentioned at the Art Institute of Chicago consists of 37 works acquired in 1982, from Chicago collectors Lindy and Edwin A. Bergman.

Taking a cue from Bergman's installation, the National Gallery will display its Cornells grouped family-style in a horizontal wall display case in an upstairs gallery. He intends to keep several Cornells in view at all times; the first rotation opens on Thursday.

The works in Lehrman's gift run chronologically from 1939 to 1969. About half are from Cornell's lush surrealist style of the 1940s, featuring Medici princes and Romantic-era ballerinas. Others belong to the minimalist style of the 1950s, especially the Aviary boxes, whose almost empty, white-painted interiors can be seen as precursors to the geometric obsessions of the minimalists of the 1960s.

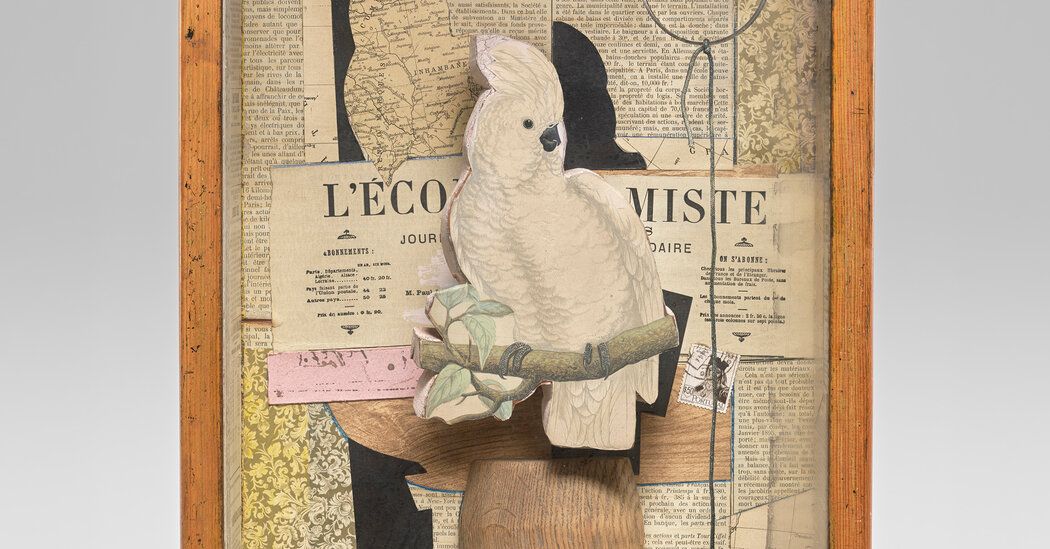

The star of the collection is “A Parrot for Juan Gris” (1953-54), a quietly fascinating object featuring a paper cutout of a white cockatoo perched on a branch. It is a strange bird that lives in a dusty room that lacks a window or view. The walls are covered with paper objects: sheets of newspaper and fragments of a map.

In some ways, the bird may seem to anticipate a Washington-type person, someone ensconced in a world of news, surrounded by headlines. But if you look closely, you will see that the newspapers are in French and faded by time. The map is of Mozambique. As in every Cornell box, all paths lead away from the present and into the mists of the imagination.