Over the past year, celebrations of hip-hop’s first five decades have attempted to capture the genre in its entirety, but some of the early stars and scenes were almost gone long before anyone came to celebrate them. Three excellent books published in recent months are responsible for cataloging the relics of hip-hop, the objects that embody its history, before they disappear.

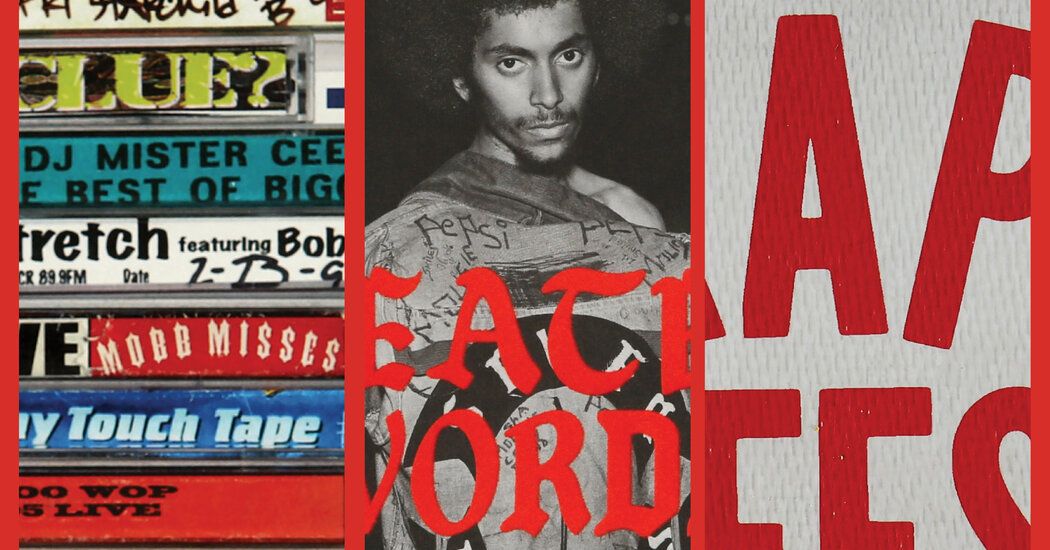

In the lovingly assembled and carefully arranged “Remember! The Golden Era of New York Hip-Hop Mixtapes.” Evan Auerbach and Daniel Isenberg wisely taxonomize the medium into distinct micro-era’s, tracing innovations in form as well as content, beginning with live recordings of party performances and DJ sets and ending with artists using the format for self-distribution and self-promotion.

For more than a decade, cassettes were the currency of mixtapes, even after CDs usurped their popularity: They were mobile, durable, and easy to duplicate. (More than one DJ raves about the Telex cassette duplicator.)

Each influential new DJ found a way to push the medium: Brucie B talks about customizing tapes for drug dealers in Harlem; Doo Wop remembers putting together a lot of exclusive freestyles for his “95 Live” and in one memorable section; Harlem DJ S&S details how he got his hands on some of his most coveted unreleased songs, sometimes angering artists in the process.

The book covers some DJs who were known for their mixes, such as Ron G, and some who were known for creating new music, such as DJ Clue. Some, like Stretch Armstrong and Bobbito, whose late-night radio shows were widely pirated before they themselves began distributing copies, achieved both.

Mixtapes were big business: a striking two-page photograph documents a handwritten inventory list from Rock ‘n’ Will’s, a historic store in Harlem, showing the breadth of stock on display. Tape Kingz formalized and helped export mixtapes globally, and more than one DJ comments that he was surprised to see their tapes available for sale when they traveled to Japan.

Mixtapes were the site of the first innovations that ended up being crucial to the industry as a whole, whether it was to demonstrate the effectiveness of street corner promotion or, through mix tapes in the late ’80s and early of the 90s, laying the foundation for hip-hop. cross-pollination of hops with R&B.

Over time, the format was co-opted as a vehicle for record labels like Bad Boy and Roc-a-Fella to introduce new music, or artists like 50 Cent and the Diplomats to release songs outside of label obligations. (The book effectively ends before the migration of mixtapes to the Internet, and does not include contributions from the South.) Even now, the legacy of the mixtape endures, the phrase a kind of shorthand for something immediate, unregulated and possibly ephemeral. But remember!” makes it clear that they also belong to posterity.

That same path from informal to formal, from informal art to big business, was traveled by hip-hop promotional merchandise, particularly the T-shirt. That story is told again and again in “Rap Tees Volume 2: A Collection of Hip-Hop T-Shirts and More 1980-2005,” by noted collector DJ Ross One.

It’s a pocket history of hip-hop conveyed through the ways people wanted to show their dedication and the ways artists wanted to be seen. In the mid-1980s, logos were stylized and elegant. Public Enemy, especially, had a strong understanding of how merchandise could increase the group’s notoriety, captured here in a wide range of shirts and jackets.

By the 1980s, hip-hop had not completely divided into thematic wings: tours often presented unexpected bedfellows. A tour T-shirt for the jovial Doug E. Fresh shows that his opening acts included the angsty agit-rap group Boogie Down Productions and the icy stoics Eric B. & Rakim.

Many of the t-shirts in the book were made by record labels for promotion, but there’s also a robust bootleg section (see the hand-painted Salt-N-Pepa denim trench coat) that reflects the untapped demand that remained long before hip -hop. fashion was considered an impregnable business.

This collection showcases some of hip-hop’s indelible logos: Nervous Records, the Diplomats, Loud Records, Outkast; t-shirts for long-defunct radio stations and magazines; impressive sections on Houston rap and Miami bass music; as well as promotional items such as Master P boxers, a tchotchke toilet for Biz Markie and an unreleased Beastie Boys skateboard. That “Volume 2” is as thick as its essential 2015 predecessor is a testament to how much there is likely left to discover, particularly in times when the archive was not a priority.

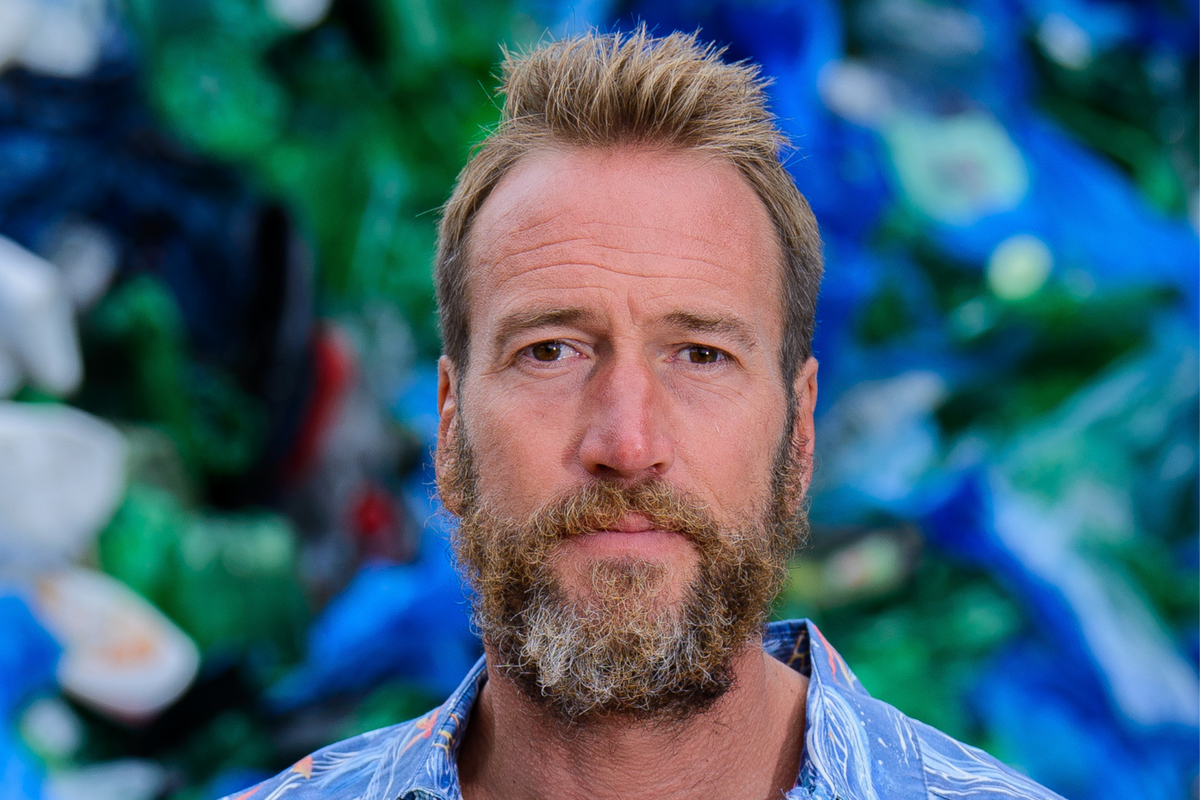

Some of the first hip-hop T-shirts on “Rap Tees” feature flocked lettering that is familiar on the backs of Hell’s Angels and B-boy groups. Aesthetics are the subject of “Heated Words: Searching for a Mysterious Typeface” by Rory McCartney and Charlie Morgan, a heroic work of sociology, archival research and history that traces the development of the style, from its historical antecedents to actual locations in New York, where young people would customize their t-shirts to adapt them to contemporary urban fashion.

This typeface, which, the authors discover, has no agreed-upon name (and no fully agreed-upon backstory), conveys “instant heritage,” typographer Jonathan Hoefler tells them. The lettering is derived from black letter or gothic typefaces, but the versions that adorned clothing during the ’60s, ’70s, and ’80s were often more idiosyncratic and sometimes handmade.

The lettering style thrived thanks to the ease of heat transfer technology, which allowed DIYers to embellish their own garments at will. It was adopted by car clubs and motorcycle gangs (and, to a lesser extent, some early sports teams). Gangs were also a type of teams, just like breakdancing groups. Shirts with these letters became de facto uniforms.

McCartney and Morgan spend a lot of time detailing how the cards came to be and tracing the places where they became fashionable: highlighting a store in the Bronx where many gangs would buy their cards, or the Orchard Street store on the Lower East Side that provided cards for The Clash. , as well as t-shirts for Malcolm McLaren’s “Double Dutch” video and the cover of a local newspaper, East Village Eye.

“Heated Words” has relatively little text: it establishes its connections through images, both professional and amateur. The book is an impressive compendium of primary sources, many of which have not been seen before, or which have been public, but not seen through this particular historical lens.

It’s a good reminder, along with “Remember!” and “Rap Tees,” that some elusive stories are not buried but crumble into barely recognizable pieces. Dedicated researchers like these can follow navigation routes and piece together something resembling the full story, but some details remain forever out of reach, evaporated into the past.