The bed in Nancy Gerrish's bright Los Feliz home looks perfectly ordinary: carved wooden headboard, plush brown blanket and cream bedskirt. The sheets have a chic leopard print. A few brocade pillows sit atop the bedspread, completing the earth-toned look.

But beneath that luxurious exterior, Gerrish's bed hides a disturbing secret.

Sit on the edge of the mattress and it will wobble and undulate. Lie down and it will rock gently, as if you were floating on a warm pool of water.

And indeed, you are.

In Los Angeles, water is all around us. Drink up, cool off, and dive into our stories about hydration and recreation in the city.

“I tell people I have a waterbed and they all laugh,” says Gerrish, a 78-year-old financial planner with curly white hair and manicured lavender nails. “But it’s a very comfortable bed to sleep on and I personally don’t know why the world doesn’t have one like it.”

If you thought waterbeds had gone the way of 1970s trends like Troll dolls and polyester suits, you're largely right. The wavy vinyl mattresses that became a symbol of the era's sex, drugs, and rock 'n' roll lifestyle may no longer be part of the collective consciousness, save as the butt of jokes in a period film or a prohibited item in a standard apartment lease. But they can still be found gently undulating in a handful of Southern California bedrooms.

According to the Specialty Sleep Association, waterbeds account for less than 2 percent of total mattress sales today, but the few remaining retailers field daily calls from stubborn people like Gerrish — mostly seniors who bought a liquid-filled mattress decades ago, fell in love with its undulating motion, and won’t sleep anywhere else. Now these waterbed enthusiasts scour the Internet for replacement mattresses, heaters, and water-treatment systems, determined to resist sleeping on standard mattresses — what they call “dead beds” — for as long as possible.

“I’m worried,” said Donna Martin, 77, of Glendale, who has been sleeping on a waterbed for 50 years. “I think if I ever have to go into a nursing home, they won’t give me a waterbed.”

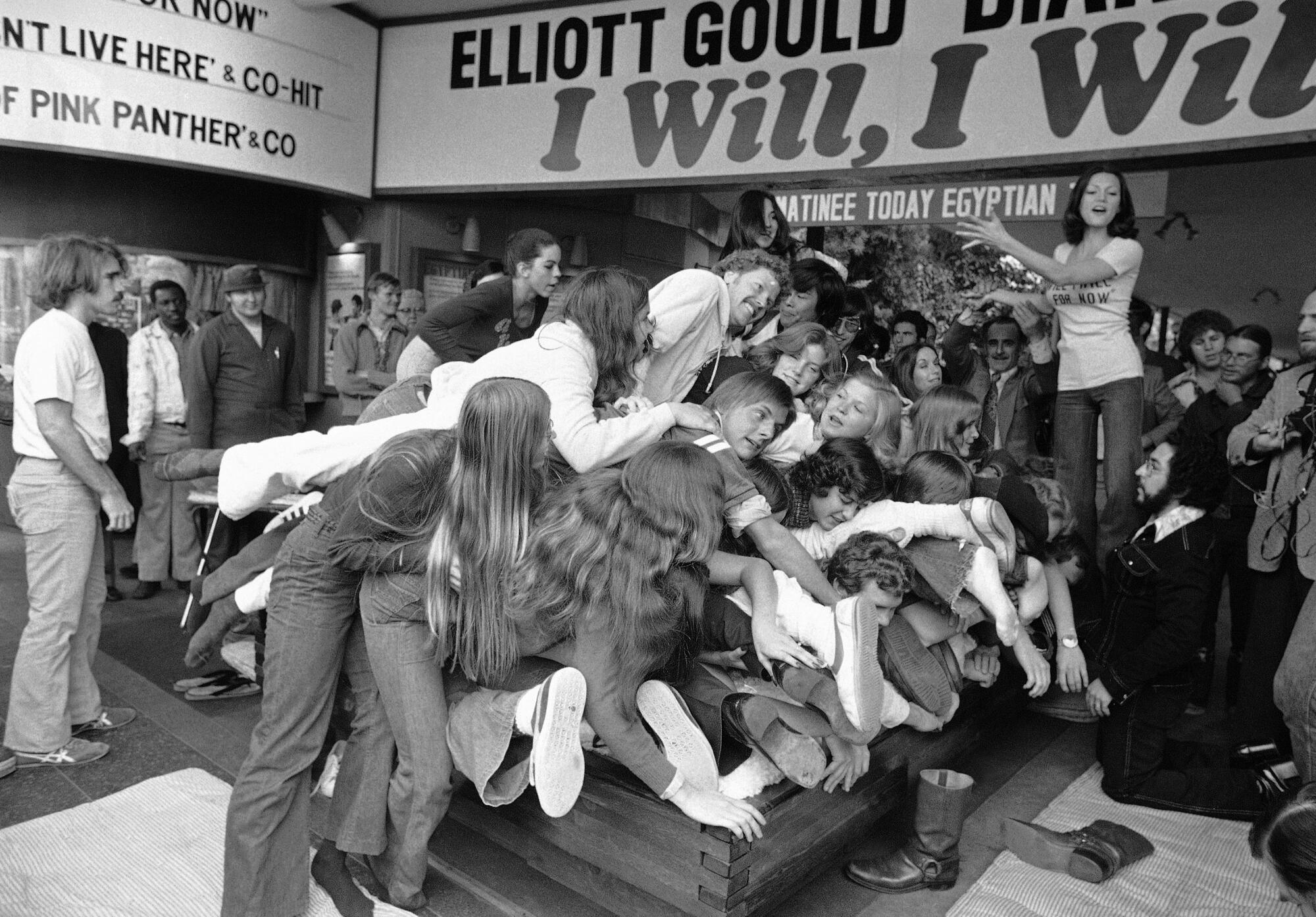

Forty-seven UCLA students pile onto a waterbed on March 10, 1976 to set a new record for a human pyramid on a waterbed in Los Angeles. According to their press agent, they broke the old record of 16 students at a publicity stunt to promote a Hollywood production that was in development at the time.

(Wally Fong/Associated Press)

The boom of the 'Pleasure Pit'

The modern waterbed was invented in 1968 by Charles Hall, a graduate student at San Francisco State University, as part of his master’s thesis in design. Hall, then 24, had set out to create the world’s most comfortable chair, filling a plastic bag with gelatin and then cornstarch with disappointing results. Eventually, he hit upon a winning formula: an 8-foot square vinyl mattress filled with water. He called it the “pleasure well” and envisioned it as a hybrid between a bed and a chair—the only piece of furniture one would ever need.

“It was new, exciting, different, sexy and fun. It was the bed of our generation.”

— Denny Boyd, former president of the Waterbed Manufacturers Association.

His prototype was featured in an exhibition called “Happy Happenings” at the Cannery art gallery in San Francisco that summer, and soon articles about the novel waterbed appeared in newspapers and magazines across the country. A modern sleep trend was born.

“It was something new, exciting, different, sexy and fun,” said Denny Boyd, a former president of the Waterbed Manufacturers Association who once owned 35 waterbed stores in Texas, Missouri and Louisiana. “It was the bed of our generation.”

According to the New York Times, sales of waterbeds soared from about $13 million in 1971 to $1.9 billion in 1986. The mattresses were fairly cheap, but sales of the heavy wooden frames that kept the mattresses from moving, plus water heaters and air conditioners, generated big bucks. By 1991, about 1 in 5 mattresses sold in the United States was liquid-filled, according to the Washington Post. Hall received a patent for his invention in 1971 but rarely enforced it, and young entrepreneurs quickly turned the waterbed business into a lucrative industry.

“There were a lot of people who became millionaires when they were 25,” Boyd said.

It was a wild, sex-filled business. One of the first ads read: “There are two things better on a waterbed. One of them is sleep.” Boyd recalls hosting sleepovers at his stores, where customers would show up in outrageous sleepwear — sheer nightgowns and G-strings. The store served wine and cheese and stayed open until 3 or 4 a.m.

“It was more than just an adult movie,” Boyd said.

Competition among the mostly male vendors was fierce. “People would throw rocks at each other’s tents and search through garbage cans for customer lists,” Boyd said. “At trade shows, you had to hire a security guard to watch the space and keep people from sneaking in and poking holes in your mattress.”

By the mid-1990s, however, the party was over. After a meteoric rise, the waterbed market dried up. Boyd says the decline was due to a handful of factors, one of which was the arrival of the “soft-sided” waterbed, which looked more like a traditional bed and didn’t require expensive bed frames or special sheets — accessories that generated the bulk of waterbed stores’ revenue. At the same time, several new alternative mattress technologies hit the market, including air mattresses, Sleep Number, Tempur-Pedic, and memory foam.

“These beds were more conventional, easier to sell and less complicated,” Boyd said. “They also had a lot of hype behind them.”

In 1995, the Waterbed Manufacturers Association changed its name to the Sleep Specialty Association.

Donna Martin, 77, rests on her waterbed in her Glendale apartment. Martin has used waterbeds for the past 50 years.

(Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Times)

There are 'heads of water' dedicated

For some, the waterbed was never a passing fad, but a lifelong devotion.

Gerrish, the Los Feliz financial planner, bought her first water-filled mattress in 1996 after sleeping on a friend’s waterbed. “I couldn’t believe how comfortable it was,” she said. “It’s very gentle on all your joints, and if you like to curl up, your arm sinks into the bed so there’s no pressure on it.”

Twenty-one years ago, she moved her waterbed from New York to Los Angeles. When she eventually sells her Los Feliz home, she hopes to take it with her wherever she moves. (She was relieved to learn that it is illegal for landlords to ban waterbeds in California in rental units built after 1973, though they can require tenants to carry insurance for damage caused by the bed.)

“I feel very comfortable. It's hard to leave here,” she said. “And everyone who visits me loves it. I think the [traditional] “Mattress companies don’t want this information to come to light.”

Gerrish has been sleeping on a water-filled mattress for 28 years, but several Los Angeles waterbed enthusiasts have had an even longer relationship with Hall's 1968 invention.

Martin, 77, of Glendale, has been sleeping on a waterbed since she received her first used bed from a friend.

“Since I first installed one, I’ve had five mattresses. I love it,” he said.

He recently slept on his sister's Swedish memory foam mattress while she was pet-sitting for the weekend. The verdict? No thanks. Martin has a crushed disk in his spine and finds the waterbed more comfortable on his hips.

“At first it was fine, but then the same thing happened, too much pressure,” he said. “I prefer not to sleep on anything else.”

A close-up of a waterbed at the Afloat factory in Corona.

(Chris Carlson/Associated Press)

Keith Koenig, CEO of City Furniture, shows off the new waterbed on display as he speaks during an interview with the Associated Press in Tamarac, Florida, in 2018. Koenig and inventor Charles Hall, pioneers of the waterbed industry in the United States, hope to spark a new wave of popularity for the age-old furniture concept by using a new, healthy tone.

(Brynn Anderson/Associated Press)

Steve Hertzmann, 62, of San Pedro, understands. He's been a fan of waterbeds for 40 years and is surprised that the squiggly mattresses have never come back into style.

“The best time is in the winter when it’s really cold,” she said. “The water bed has a heater and you get in it and you’re nice and warm.”

Marty Pojar, who runs a shop called Waterbed Doctor in Westminster, would love to see a revival, but thinks the technology needs a rebrand.

“The word ‘waterbed’ creates a stigma,” she said. “When people hear it, they think of the big, old, wooden-framed waterbeds with lots of wave action.”

In fact, waterbeds have evolved over the years. Consumers can now choose between mattresses that offer traditional-style full-motion waves and those that have no waves or virtually no waves. Many beds also have two separate waterbeds, one on each side, so that if two people sleep together and one of them gets out of bed, the other does not experience any movement.

With enough advertising money behind him, Pojar believes that rebranding the waterbeds as “temperature-controlled floating sleep systems” could attract new customers.

“Re-educating the public is a big challenge, but I think there is a big opportunity there,” Pojar said.

For now, his longtime fans are keeping his business alive. Change can be tough for a lifelong waterbed fanatic, as Larry Johnson of Mar Vista has seen firsthand.

The accountant slept on a waterbed for 50 years, until May, when his wife convinced him that a standard mattress would allow him to get out of bed more easily as he got older.

After a few days, Johnson was undecided. The “dead bed” wasn’t as soft as his waterbed. He missed the rocking motion.

“It's going to take some time to get used to,” he said.