“These are probably the last tamales I will make,” says my aunt and godmother Vicky as she hands me bags full of four varieties.

This may not be an honest prediction: in fact, Tia Vicky has made this announcement every year for the past 15 years. Still, she is 82 years old and his voice is hoarse due to health problems.

Unpack the loot: pork in red sauce with potatoes; rajas (made with strips of pasilla chili, cotija cheese and tomatillo green sauce); chicken cooked in tomato and onion sauce, jalapeño and olives; and sweet tamales sprinkled with grated coconut, pineapple, raisins and sugar.

How could this end or even change?

These tamales are the heartstrings that keep my cousins, our children, now second, third and fourth generations, and me, connected to our ancestral home in Nayarit, Mexico: our culinary line to a homeland from which we are not .

Made from masa, a dough made from corn, tamales represent not only Mexican cuisine but also our Mexican identity. We are “gente de maiz” – people of the corn.

Every year, my family reaffirms this in the week before Christmas, when we gather in my Tia Vicky's kitchen (my mom, our neighbor Angela, and all the other cousins, friends, and grandchildren we can muster) to make tamales for the holiday. . Our fun and festive time together is about making the tamales, but it's also about being on the ball., together.

This is the tamalada. I'm on my way home from work at USC, my cousin Karla is coming to pick up her kids after work and we sit around the table laughing and gossiping and drinking Pinot Noir.

The kitchen looks smaller than it is because my aunt's table takes up three-quarters of the space. The table is beautiful, made of heavy black lacquered wood with a sun and moon motif, but it is more appropriate for a Mexican hacienda than a modest home. About 25 years ago, my aunt saw it on a soap opera and when she saw the same table in a furniture store, she grabbed it. It's like being on stage.

(Nicole Medina / For The Times)

No matter how many years we've been making tamales, one of my aunts will tell me I'm doing it wrong. My tamales are too fat, so they don't steam evenly when it comes time to cook them. Or they are too thin, making the dough crumbly and crumbly. My nephews are on an even tighter leash, limited to making the sweet tamales, which only require spreading the dough their grandmother already prepared on the sheet.

To be fair, my aunts weren't entirely exaggerating about our amateur tamale-making skills. After all, who could forget the year Karla kneaded dough with her hands and Lee's nails ended up in it? She realized this mishap only after the tamales were ready.

We take photos and post them on social media. But as a historian accustomed to reading sources, I know that images are not always an accurate representation of what is happening. The photos are Latinidad-Potemkin: Images of the Latina women that Karla and I will never be, the kind who have the skill, patience and time to put their lives on hold for three days to make hundreds of tamales.

But we do recognize the importance of tradition, even if we are acting. These tamales and the traditions that surround them keep us united to each other and to Mexico, specifically to our family in Nayarit. Our mothers gather us here in this space every year because that tradition is essential.

And yet we have not been prepared to continue the tradition ourselves.

My mother and aunts were more concerned about their daughters receiving an education than learning to cook. They wanted us to have the opportunities that they hadn't had. When I was in my teens and 20s, I would ask Tia Vicky to teach me how to make some of her signature dishes, like gorditas (a thick bag of corn stuffed with chicken, beef, or pork) smothered in a light sauce made with broth. of fresh chicken. tomato and a little garlic.

“Mija,” he responded, “you are very busy studying. You can learn when you finish school.”

But even when I finished school, more school, work, and family came along, and somehow I never learned to cook beyond the kind of 30-minute meal for four found in a recipe ripped from a magazine or newspaper. I wouldn't even know where to start cooking for dozens of people.

So when Tia Vicky makes her annual announcement that this year could be her last, I don't feel guilty or resentful. Because, honestly, it takes a lot of work to make tamales, and that work is often taken for granted.

The women (they're almost always women) spend three days making tamales: buying the ingredients, sorting and soaking the leaves in heavy buckets of cold water, preparing the fillings, making the pre-dawn pilgrimage to the Amapola market (yes, that one Poppyheadquarters of the 2016 Tamale Apocalypse) in Downey to stand in line, sometimes for hours, to buy the dough.

And then the day of the preparation itself. They make 300 to 400 tamales, enough for our entire family to share during the winter holiday cycle: Christmas Eve, New Year's Eve, Epiphany, and Candlemas Day. We prepare for the holidays.

Although the tamales are ready at my aunt's house, she will not deliver them to us, the hosts, beforehand. She and my uncle, who no longer drive at night, bring them in an Uber. I always wonder what the driver thinks of these two octogenarian Lilliputians carrying a steel pot the size of a small trash can, full of hot tamales.

For Christmas Eve we met at my house. When I returned to Los Angeles from San Diego in 2018 after 18 years, it was declared that I would now be responsible for organizing Christmas Eve and it never crossed my mind to question it.

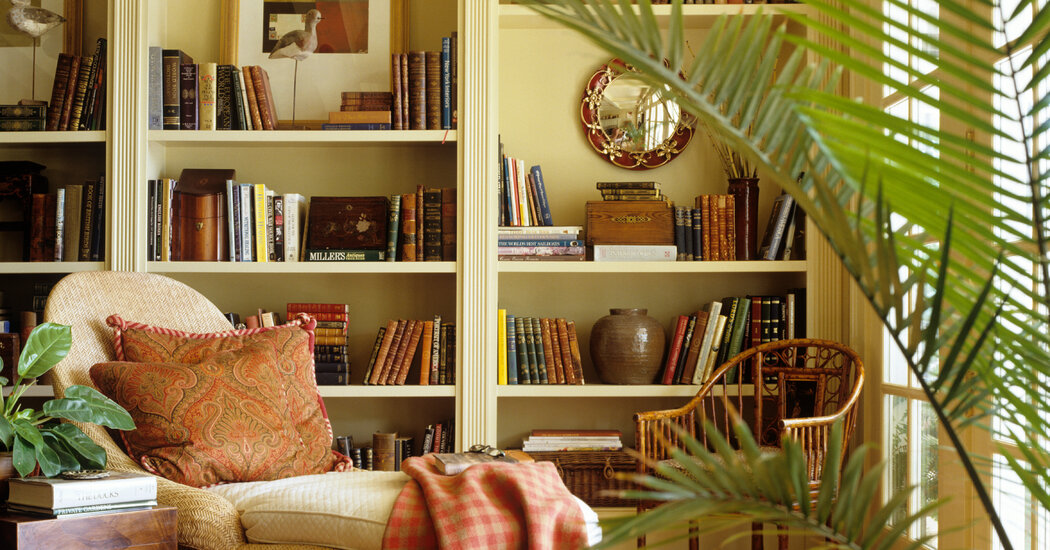

A three-day event, the annual tamalada at Tia Vicky's brings together cousins and children around a table in her kitchen to prepare tamales for the holidays.

(Natalia Molina)

My white American husband prepares his traditional menu of ribs and all the sides, including the German noodles his grandmother Ethel used to make every holiday. He also has an immigrant tradition, although it is not easy to read it as such.

But we always have tamales too. Even Karla, who doesn't eat meat, enjoys a pork tamale because tradition trumps vegetarianism. My personal favorite is the rajas with its dense seitan-like cheese, a meaty, chewy delight.

The kids go for the sweet tamales during dinner. The rest of us can reserve them for dessert accompanied by a cup of champurrado, or wait until the morning when we can split them, fry them and savor them with leftovers or a fried egg. These tamales taste exactly the same whether we eat them at home in Pasadena, at Tía Vicky's kitchen table in Echo Park or at my Tía Nelly's kitchen table in Acaponeta, Nayarit.

Many of our connections with Nayarit are fraying. My Spanish, although my first language, has deteriorated over the years as I speak, read and write more in English. Between cartel violence and the pandemic, plus climate change making summers unbearably hot and humid, we just don't visit Nayarit as much. My mother's generation is now in their 80s and 90s, which makes traveling even more difficult. These tamales are one of the last vestiges of what makes us feel not only connected but equal.

So who will maintain that connection and make the tamales once this generation can't anymore? WHO can? Who has the time and skill?

Last Christmas Eve, my aunt posed the question once again while the adult women of the family were sitting around my kitchen table. When my aunt left, my nephew Justin's fiancée, Kassy, a strong self-taught cook with a sense of adventure, spoke up. I'd be happy to make them, she said. My cousins and I looked at her in disbelief. “You're crazy?” we asked. “You're 28 years old. You'll be doing them for the next 60 years.”

In part, we were trying to protect her. If she assumes the role of tamale, she could technically stop doing it whenever she wants, but (as in many families) it is difficult, especially for women, to get out of a role once she assumes it.

But a deeper reason for our shock was that Kassy is Salvadoran-American. Her family makes a different type of tamale: larger and flatter, wrapped in a dark green banana leaf and seasoned with cilantro and cloves. Our Nayarit tamales contain bone-in pork and pitted green olives, and we've been eating them for so long that our tongue unconsciously navigates to separate the meat from the bones and seeds. Kassy's tamales are tasty and moist, but they are not. our Tamales.

Justin chimed in: “They're good. In fact, I prefer them now.”

“Never say that to Tia Vicky,” I replied.

It's not that we couldn't appreciate these delicious tamales; rather, at that moment it felt almost like a rejection of Mexico and our family. If we embrace these other tamales, if the fiber of our heart that returns to Nayarit is intertwined with other strands, who will we become? However, isn't that complex, beautiful, ever-changing braid the essence of tradition?

Tradition is not just about holding on to the past: it is a celebration of the way our hearts and families evolve and intertwine to bring in new members and new practices, a chance to love and honor the past even as we welcome change. in our lives. .

The family prepares 300 to 400 tamales, enough for everyone to share during the winter holiday cycle: Christmas Eve, New Year's Eve, Three Kings' Eve and Candlemas Day.

(Natalia Molina)