Song-tae Kim and 17 of his church friends chatted loudly, some fueled by soju, with the remains of their dinner (black bean noodles and spicy seafood noodle soup) spread out in front of them.

For dessert, they shared slices of Korean pear that they had brought from home.

This was the group's last meal at Dragon, a Korean-style Chinese restaurant in Koreatown. They have met there twice a month for two decades.

The Brown family dine on one of the last days of business at the Dragon on January 13 in Los Angeles.

(Michael Blackshire / Los Angeles Times)

The Dragon will close Sunday after more than 40 years of serving dishes like jajangmyeon (the aforementioned black bean noodles), jjamppong (the seafood soup) and tangsuyuk (sweet and sour pork) to Korean Americans who converge from across the south Of California.

With its private rooms and spacious banquet spaces, the Dragon has hosted countless first birthday parties or doljanchi, and 80th birthday, or palsun.

In addition to regular gatherings with her friends from St. Agnes Korean Catholic Church, Kim has enjoyed many family meals and birthdays at the Dragon, which is her “dangol” or go to a restaurant. Kim, a resident of Koreatown, immigrated to the United States in 1978 and operated a sewing factory for 35 years.

“It's a shame,” said Kim, 74. “We meet here twice a month and now we need to find another place, but there is no place like this.”

Members of St. Agnes Korean Catholic Church smile and laugh as they finish their dinner at the Dragon on January 13 in Los Angeles.

(Michael Blackshire / Los Angeles Times)

Deok-jeong Wang, who founded the restaurant and owns the property, plans to convert it into mixed-use affordable housing. But he said the driving force behind his decision is not profit. Food quality is declining, he said, because it is difficult to recruit chefs skilled in Korean-Chinese cuisine, which originated with Chinese immigrants in South Korea and puts a Korean twist on northern Chinese dishes.

For example, Chinese zhajiangmian is usually simpler than Korean-Chinese jajangmyeon., which is coated with a thick fermented black bean sauce.

“To cook these very traditional dishes, you need someone who has those special skills, but there aren't many of those chefs anymore,” Wang said. “Many chefs emigrated from Korea at the beginning, but generation after generation, young people don't do it anymore. do”.

Like many who work in Korean-Chinese restaurants, Wang is of Chinese descent and grew up in South Korea.

After arriving in the United States in 1971, Wang took any job he could find: busboy, grocery deliveryman, sous chef. In 1974, he opened a Korean-style Chinese restaurant which became Dragon in 1980.

Dragon manager Wei Chou takes orders on one of the restaurant's last days.

(Michael Blackshire / Los Angeles Times)

Wang sold the restaurant to In-seung Choi in 2016, retaining ownership of the property on South Vermont Avenue north of Olympic Boulevard.

In recent years, density bonuses and other incentives have led to a surge in affordable housing development in Koreatown, one of the densest neighborhoods in Los Angeles.

Construction of the six-story, 90-unit building that will replace the Dragon is scheduled to begin in March, according to Choi.

Choi said he once owned four Korean-Chinese restaurants, but sold them after dealing with a shortage of chefs.

The House of Joy Chinese restaurant in Glendale, which sold in 2021, could do with Latino chefs trained to cook, because about half of the customers are not Korean, said Choi, who owns more than 10 restaurants in the Los Angeles area.

The Dragon also has its share of non-Korean customers, but Choi said many of the Koreans “are from the older generation, more demanding and sensitive to changes in food.”

Younger South Korean chefs don't want to move to Los Angeles because of the high cost of living and relatively low salaries, Choi added, which is also a problem for Korean restaurants serving traditional Korean food.

“The head chef, who has worked at Dragon for more than 30 years, is now in his 70s and it has been more than a year since he said his wrists hurt,” Choi said. “We knew it was time to close the store.”

Members of St. Agnes Korean Catholic Church dine while one shows off his bottle of Jinro Chamisul soju at the Dragon.

(Michael Blackshire / Los Angeles Times)

Hobin Chang, owner of Young King Korean-Chinese restaurant in Koreatown, said he has similar recruiting problems.

“It's difficult, but we managed to find, for example, some people from Hong Kong and China who live in Los Angeles, and we trained them,” Chang said.

The Dragon was originally scheduled to close last June, but remained open largely to keep about 20 employees employed, Choi said.

Choi said he feels really bad about closing the restaurant and leaving the workers out of work.

“I personally have many memories of this restaurant,” he said. “This is where my parents and my wife's parents officially met before we got married in 2001.”

Staff had hoped the restaurant would move to another location, but Choi said a large space suitable for traditional Korean celebrations would be prohibitively expensive.

“Without the large size and special spaces to host events, it wouldn't be the Dragon anymore,” Choi said. “It would just be another Chinese restaurant. “We could find any small place to continue the restaurant, but it would lose its meaning.”

Peter Nam, 68, has been coming to the Dragon since he came to Los Angeles from South Korea in 1982. Every second Saturday of the month, he has dinner there with a group of about 10 friends.

“It's a very sad feeling, because I've been coming here for more than 40 years,” Nam said as he finished a plate of sweet and spicy shrimp during his final dinner at the Dragon. “We've been talking about where the next restaurant will be where we can all get together, but we're not so sure.”

As the St. Agnes Church group finished their dinner, Joanne Lee passed around a second round of freshly cut Korean pears, pushing aside half-finished plates of jajangmyeon and sea food soup.

“We have to find another place for our meetings, but it's hard to find a place that fits a large group and has as good service as the Dragon,” said Lee, 70. “They even allow us to bring our own dessert and alcohol.” “The restaurant because we are very familiar with the staff.”

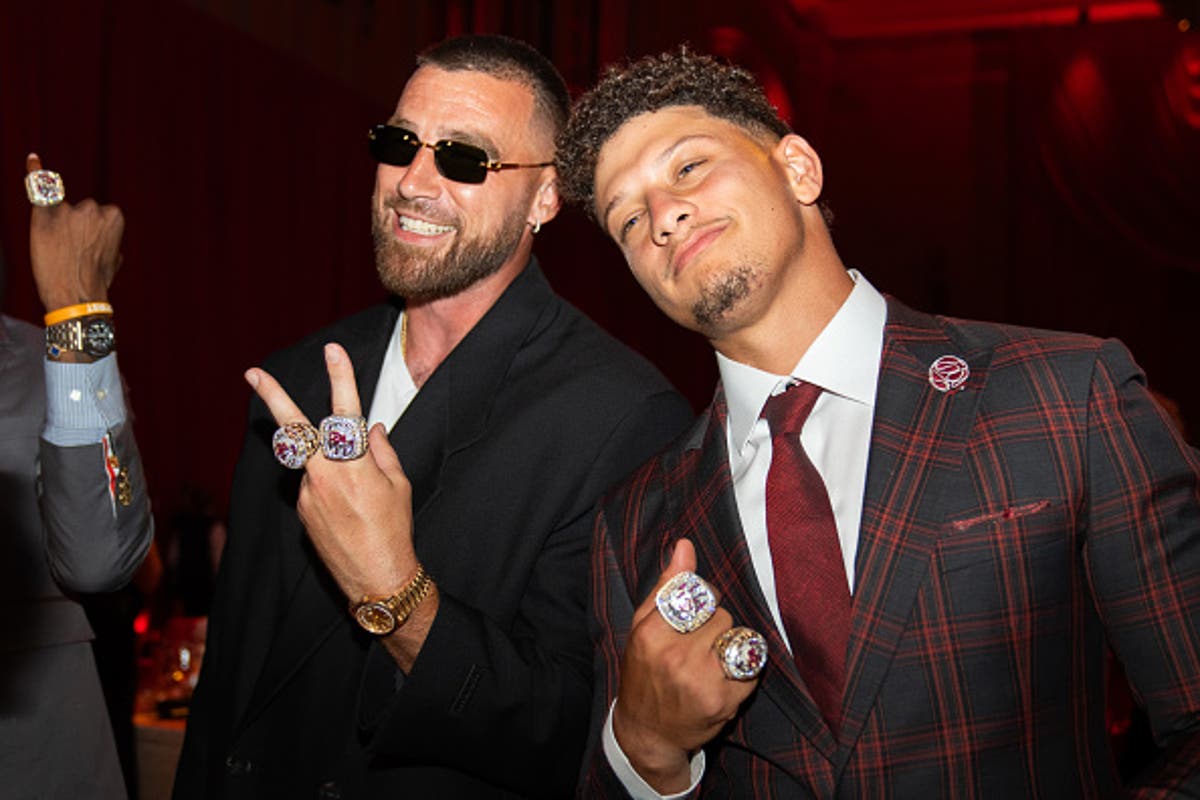

Large groups regularly came to the Dragon to dine together.

(Michael Blackshire / Los Angeles Times)

In Korean, aswiwo It means sadness, pity and disappointment all in one – an apt description of how the clients felt during the Dragon's last days.

“Aswiwo, aswiwo,” Lee and several friends said, all shaking their heads.