For nearly 100 years, Koda Farms grew some of the country's most prized rice in less than ideal conditions.

Their rice was a delicate crop, slow to sprout, skinny and tall, with fewer grains per bunch and heads that could fall out of reach of the thresher and end up in the mud.

Their land is more than 100 miles south of the Sacramento Valley, where 97 percent of the state’s rice crop is grown. Its soil is a clay-rich mix that doesn’t absorb water well, creating environmental challenges that prompted the farm’s founder, Keisaburo Koda, to pioneer a planting process in which fields are flooded before low-flying planes scatter the seeds.

Sho-Chiku-Bai sweet rice is sifted by Robin Koda's hands from a small seed silo on the Koda family farm.

But the limitations of the land are their birthright, said Robin Koda, Keisaburo’s granddaughter, a legacy of struggles overcome. They still work the 1,000 hectares that were all that remained of Keisaburo’s estate after he and his family returned from a concentration camp after World War II. They live in a house just down the road from the rice mill he owned, within sight of the houses that were taken from them and never returned.

Koda Farms, which is closing operations this year and turning over its trademarks to another family-owned company, exists in large part because of her grandfather’s optimism about America, Robin said. It persisted because of the family’s willingness to accept thorns to grow roses — or in this case, to grow rice, slightly sweet with a pearly sheen and a chewy, soft texture.

“My grandfather, no matter how downtrodden and mistreated he was, never lost his enthusiasm for America,” Robin said.

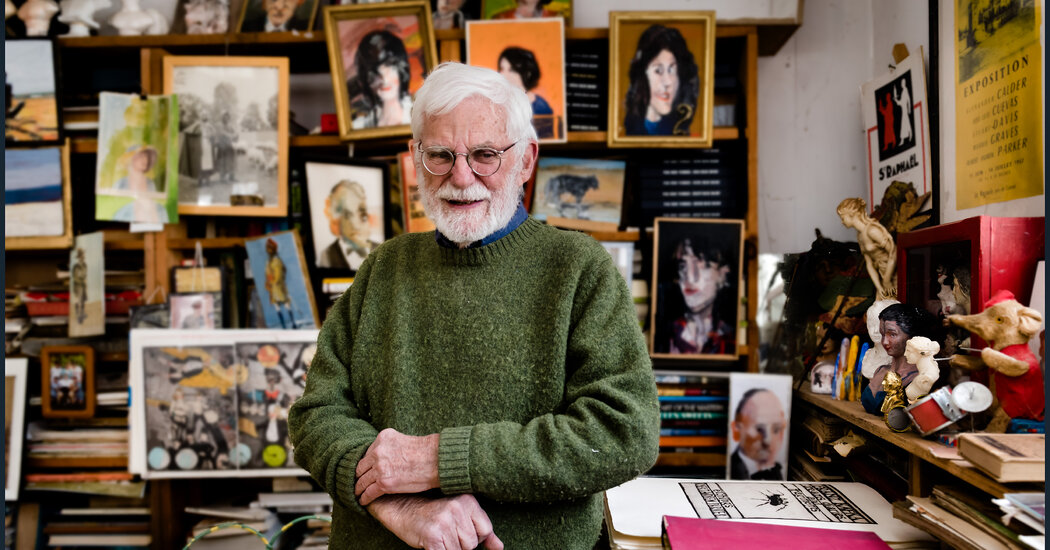

Robin Koda is shown on the family farm he runs with his brother as they transition production to their trademarked license after being in business for nearly a century in South Dos Palos. His grandfather became known as “the Rice King.”

Keisaburo was born in Fukushima Prefecture in 1882 to a samurai family of rice farmers. He worked as a school principal before emigrating to California in 1908. He was inspired by the book “Kings of Fortune,” which detailed the achievements of American businessmen such as Cornelius Vanderbilt and Eli Whitney. The preface made the following statement about the United States:

“Neither class distinctions nor social prejudices, nor differences of birth, religion or ideas, can prevent the man of true merit from obtaining the just reward of his labors in this favored land.”

Keisaburo pursued success with the tenacity of a second son excluded from the family business and forced to make his own way in the world. Upon his arrival, he started a tuna cannery, sold canned goods, opened a chain of laundries in the Coalinga area and even spent some time exploring for oil. He found his greatest success in rice, when he opened a farm with his sons Bill and Ed north of Sacramento. He was so successful that the Japanese community of the day called him “the rice king.”

Keisaburo knew that Californians resented the financial success of early Asian immigrants. He gave his companies innocuous names like State Farming Co., North America Tuna Canning and Golden West Canning to avoid racism and xenophobia. It's also why his children have biblical names.

Robin Koda, left, stands with his 99-year-old mother, Tama, who was the innovative mind that helped develop the family farm.

But it was all taken away, one way or another, after Keisaburo and his family were forced into a Colorado concentration camp by the U.S. government during World War II. When he returned, all that remained of his empire was the 1,000 acres where Koda Farms now stands.

Two generations later, it’s hard to know exactly why Keisaburo rebuilt his life so close to the memories of all that was taken from his family. But what is clear is that Keisaburo valued his American identity and eventually became a naturalized citizen. He helped create banks, exchange programs and other institutions to help Japanese Americans rebuild their lives after war and incarceration.

He lost his property, but not his power. After the war, he was known to drive around the state with a pressure cooker in the back of his sedan so that he could demonstrate the merits of brown rice when asked. He fought to recover his stolen property in court until the day he died in 1964. A year after his death, the U.S. government settled the family's case for just $100,000.

Robin and his brother Ross believe their grandfather's decision was more pragmatic than defiant. His land was all that was left to the family.

“It didn't really matter where you went. There would always be prejudice after the war,” Robin said.

Small seed silos are shown on the Koda family farm in southern Dos Palos.

Koda Farms is located in the town of South Dos Palos, a rural outpost of fewer than 2,000 people. There is no mail delivery here, and it can take 45 minutes for sheriff's deputies to show up to a call. A few years ago, Robin had to personally chase down an intruder who broke into her home through the front door. She remembers emptying her pistol's magazine into the night sky and screaming at the top of her lungs. “You know, just to let them know a crazy person lives here,” she explained.

They were the only Asian family in town when their grandfather moved in a century ago, and the 2020 census puts the town’s Asian population at 12. It is a conservative, soccer-loving town where many people grew up hunting. The company offices sport a large collection of stuffed deer heads, many of them shot by Keisaburo. Bags of rice and barley from past quality inspections act as paperweights for stacks of files and manuals.

When Ross and Robin rejoined the business full-time in 1998, Koda Farms was an aging operation in a time of rapid modernization. Ross, the only son, faced the impossible task of matching the legacy left by his grandfather, who dominated the California rice trade in his day.

Robin Koda is with Gary Wallace, who has been with the company for nearly 60 years on the family farm.

Koda was large enough to have the costs of a large farm, but too small to ignore the dramatic fluctuations in the price and availability of water and natural gas. The family competed with much larger farms, operations that produced higher-yielding crops in a more ideal climate. Large Japanese food distributors began promoting their own brand of rice instead of Koda Farms’. New food-handling regulations brought costly equipment upgrades. Computerized inventory management led grocery stores to measure a product’s success by turnover.

But Koda Farms has shipped its flour product, Mochiko Blue Star Rice Flour, in a wholesale package of 36 boxes since the 1940s, which naturally takes longer to turn the box around. And the box, which has also changed since the beginning, has a perforated spout that can cause a bit of a mess. In my pantry, my own box is sealed with tape.

Not surprisingly, both brothers took time away from the business. Ross left the farm for a few years and worked in finance in Chicago. Robin became an artist who exhibited her work in galleries and lived in France and Los Angeles. But in the end, the call of blood and soil was too strong.

Like their ancestors, they set out to make the best of a difficult situation. In an era when water efficiency had become an advantage, their clay soil helped them conserve water. Ross oversaw a shift to organic farming methods. Robin’s representation as an ambassador for Koda Farms rice helped place it on the menus of upscale restaurants in California and around the country.

But the economic and environmental realities of farming in California eventually made it too difficult to continue, Ross said. Licensing his rice brand to Western Foods was a difficult decision, but it means the crop will continue to be grown to the family’s specifications and remain on supermarket shelves, Robin said. Western Foods CEO Miguel Reyna, a Central Valley native whose parents were farmworkers, has worked with the family for nearly a decade.

“This is how we can sleep at night, because we meet all the specifications that we produce,” Robin said.

The family owns the trademarks largely thanks to Tama Koda, their mother, who persuaded the family to formalize the trademark license for Kokuho Rose and encouraged them to tell their story.

One of its first licensees was Nomura Co., which introduced its rice, Kokuho Rose, to Asian supermarkets across the United States.

Kokuho means “national treasure” in Japanese. The red logo on the rice (an eight-sided mirror with a heavenly sword) looked familiar, so I sent a photo of the bag to my mom in Fremont.

Turns out I've been eating it all my life. It's the rice we used when I was a kid in Tennessee, bought at the little Asian grocery store at the Nashville farmers market.

I assumed it was an imported product like everything else in that store, but it was an American rice, created by an American family.

Robin Koda walks out of a warehouse on the family farm. The economic and environmental realities of farming in California eventually made it too difficult to continue, his brother Ross said.