After Yuval Sharon became artistic director of the Michigan Opera Theater in 2020, the company was renamed Detroit Opera, perhaps the most visible move that has led to a remarkable run of success based on an ambitious new approach.

The house has placed itself at the center of the operatic conversation with productions such as the drive-through “Götterdämmerung” and a virtual reality “Walküre.” It has broken fundraising records, attracted thousands of first-time ticket buyers and collaborated further with businesses elsewhere. Robert O’Hara’s staging of Anthony Davis’s “X: The Life and Times of Malcolm X” at the Metropolitan Opera last November, for example, began a year and a half earlier in Michigan; the Met asked Detroit if it could join the production, not the other way around.

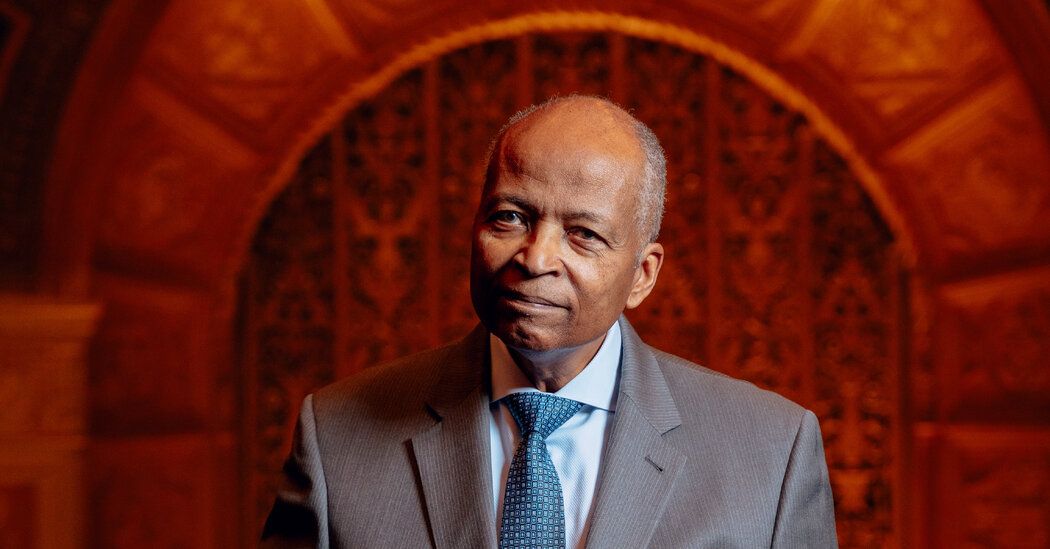

Sharon receives most of the praise for Detroit’s rise in fortunes, but little of its advancement would have been possible without the courage and insight of Wayne Brown. Brown, one of the few Black leaders in the field, served as president and CEO of the Detroit Opera from 2014 until his retirement at the end of 2023.

“Wayne has always been wonderful to deal with,” said Met CEO Peter Gelb. “You don’t necessarily think of Detroit as a center of opera production or creativity, but by hiring Yuval he has achieved that. He has changed that impression of Detroit.”

Brown, 75, is a veteran executive with nearly half a century of varied experience, from stints in regional symphony orchestras to a stint from 1997 to 2014 as director of music and opera at the National Endowment for the Arts. Even after his retirement, his enthusiasm for the process of putting on a show remains infectious.

“The fascinating thing is making sure those connections can be made,” Brown said. “It’s not just about transactions; It’s about how do you find that sweet spot where art and audience align?

Brown is widely admired on the field for being a leader who is different from the norm and reluctant to be the center of attention.

“He has been a unifier of people,” said Deborah Borda, former director of the New York and Los Angeles Philharmonics, who has known Brown since the 1970s. “He has a very quiet strength. He has a kind word for everyone, something quite unusual in our business. I think he is considered somewhat Solomonic.”

Davóne Tines, the bass-baritone who worked as artist-in-residence at the Detroit Opera in 2021 and 2022, said Brown’s support of creativity was exemplary, especially as “a young Black creator whose career began in arts administration.” ”.

“Someone in the position of CEO or senior executive of an opera company may have presuppositions about what kind of person they might be,” Tines said. “He is a man of incredible gravity and carries himself with a dignity that is very inspiring. It’s wonderful to see that balance with how genuinely curious he is.”

Brown’s musical life began by learning to play the violin in the fourth grade and then the cello. As a student at the University of Michigan, he joined the men’s Glee club and was its president. “Increasingly, what mattered was not just performance,” he said, “but performance with context, the whole notion of making it work.”

Shortly before Brown graduated from college, the dean of the music school asked him if he would be interested in a job with the Detroit Symphony Orchestra, which was looking for an assistant administrator. “I said sure,” he recalled. “I mean, I didn’t know what he was.” He was quickly promoted to assistant conductor and embarked on a career working for orchestras that later included serving as executive director of the Springfield Symphony Orchestra in Massachusetts and, for a decade, of the Louisville Orchestra.

Brown also briefly worked as a producer for the Cultural Olympiad that took place during the 1996 Atlanta Olympics, a competition that included jazz, opera, chamber music and more. “Those were interesting opportunities,” he said, smiling.

Borda recalled the tact with which Brown later convened the expert panels that advised the National Endowment for the Arts on its grants. “You had to go to Washington, DC for four days, you had to literally review a hundred applications and listen to them to do a good job,” he said. Brown made a cumbersome process more meaningful. “When Wayne was there, I think he invited me almost every year and I would go. After Wayne, I didn’t do it anymore.”

Brown speaks fondly of the public service opportunity the NEA gave him and learned useful lessons from the opportunity it gave him to see the field as a whole. “You can’t necessarily apply a scenario that’s happening in one community to another,” he said. “Innovation is a relative term. “Something can be innovative but be perceived as simply a marginal difference in the broader environment.”

Context certainly counted in Brown’s decision to return to Detroit to direct the Michigan Opera Theater in 2014. Returning to the city where he had begun his career, Brown was determined to secure what the downtown house’s former leader, David DiChiera, had achieved after founding the company. in 1971, four years after the 1967 race riots in the city.

“If I could play a role in a place that mattered to me, a place that inspired me, I couldn’t imagine at that time any other role that would have been of interest,” Brown said. “We wanted to make sure we could convey a message of openness, inclusivity and level of engagement.”

Marc Scorca, president of Opera America, believes Brown was the ideal person to manage the house’s transformation following DiChiera’s retirement. “It was Wayne’s extraordinary diplomacy that allowed that transition to occur with respect and dignity,” Scorca said.

Hiring Sharon in the midst of the coronavirus pandemic was a tribute of sorts to the theater’s founding mission. DiChiera, Brown said, “had an interest in making sure that what was happening in Detroit could have a broad impact.” However, the theater was nothing if it was not rooted in its city.

Sharon took office promising not only to make the house the most progressive in America, but also to integrate it even more deeply into his community, even asking that it change its name when he arrived. Brown urged moderation, so they could do the patient work necessary to build consensus.

“My approach was very impulsive,” Sharon said. “Wayne’s more analytical and thoughtful approach, and his calm way of thinking about these things, meant that when we finally voted on it, we had the full support of the board.”

“I really saw the value,” Sharon added, “of what it means to not necessarily go into things like a bull in a china shop.”

Sharon highlighted the co-production of “X” as Brown’s other major accomplishment during their time working together at Michigan. “It was really outside the scope of what the company has ever done in terms of scale,” Sharon said. Nearly half of the crowd at the sold-out race in Detroit were visiting the company for the first time.

“The art form spans centuries; it doesn’t stop,” Brown said of the opera. “It’s about moving forward and being bold about it, and there’s no better time to do it than now.”