Truly support

independent journalism

Our mission is to provide unbiased, fact-based reporting that holds the powerful to account and exposes the truth.

Whether it's $5 or $50, every contribution counts.

Support us in offering journalism without agenda.

IWhen recent allegations about Strictly come dancingI barely raised an eyebrow. The much-loved show, a symbol of Britishness on par with crumpets, Paddington Bear and the royal family, had previously enjoyed a relatively scandal-free reputation (well, apart from all the celebrities getting off on their dance partners). Now, its clean streak was over, tainted by allegations of bullying and abusive behaviour from past contestants; the BBC was forced to apologise and kick two professional dancers off the cast.

My lack of reaction was due to the fact that we seem to have reached a point in our national culture where everything that once made “Britain” great has been tainted in one way or another, reduced to a predictably disappointing mishmash.

That's why I was also not surprised to see that, across all measures, British pride in our country has declined since 2013, according to a new report from the National Centre for Social Research (NatCen).

Asked if they were “very proud” of Britain across a range of criteria, all 1,600 respondents from England, Scotland and Wales said yes: 64 per cent of its history, down from 86 per cent a decade ago; 53 per cent of the way democracy works, down from 69 per cent; 44 per cent of our economic achievements, down from 57 per cent; 48 per cent of Britain’s political influence, down from 59 per cent; and 77 per cent of its achievements in sport, down from 84 per cent. The highest level of pride and the smallest decline were in the arts and literature – 79 per cent, down from 80 per cent in 2013.

Given the events of the past ten years, the real surprise is that the decline has not been greater. After all, we have been hit from every conceivable direction. Brexit has stripped us of our political influence on the world stage, tanked the economy and left us waiting for ages at airports in queues of non-EU members. Our Conservative government during the COVID pandemic will forever be remembered both for its cronyism (doling out lucrative PPE contracts to inexperienced colleagues) and its gleeful flouting of its own lockdown rules with numerous parties (not to mention Dominic Cummings saying “I drove to Barnard Castle to test my eyesight”).

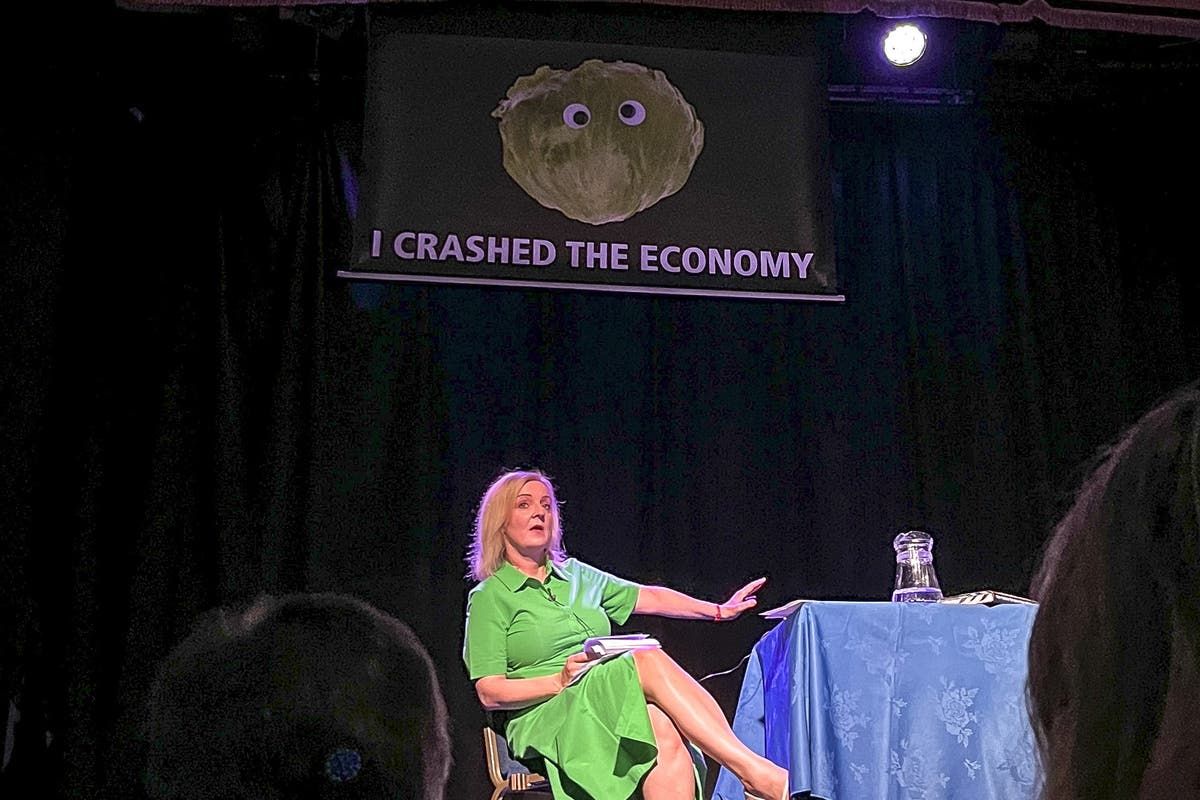

Boris Johnson presided over scandal after scandal; Rishi Sunak ruined everyone else’s Adidas Sambas on a whim. And good old Liz Truss, with a prime ministerial life shorter than a head of lettuce, further increased our international laughingstock status and sent mortgage rates soaring as a parting gift.

A surge in far-right rhetoric saw Nigel Farage’s smug face appear on our screens just when we finally thought we had put him behind us, leading to disastrous policies such as trying to fly all our asylum seekers to Rwanda. and gave rise to Reform UK to pick up where UKIP had left off.

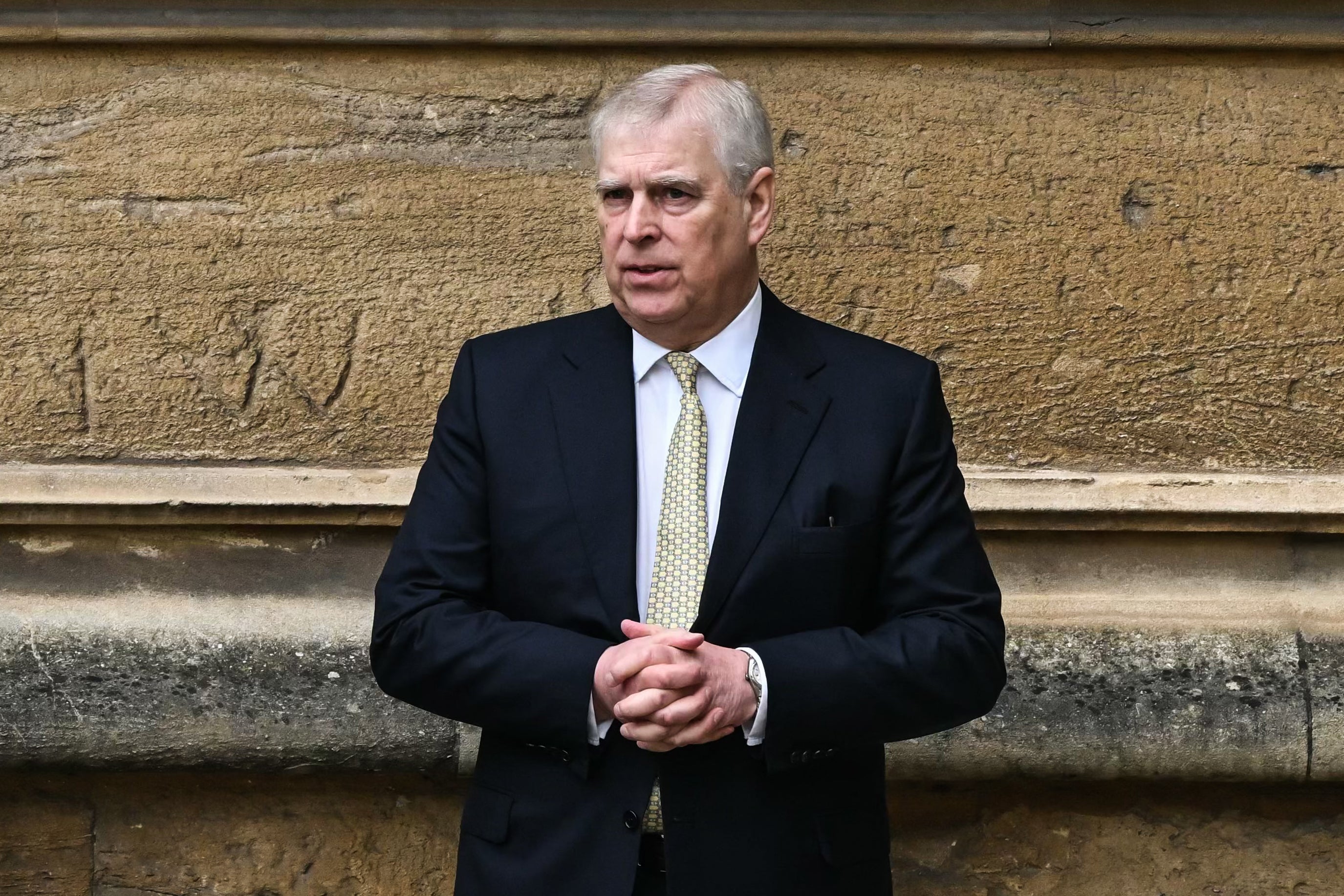

Then there is the monarchy, traditionally one of Britain's greatest promoters of patriotism, which has experienced one of the most eventful decades in living memory. The death of the universally adored Queen Elizabeth II; sexual abuse allegations against Prince Andrew; Meghan and Harry pushed to the edge and hounded out of the country; a bitter split between the princes and the ensuing tell-all autobiography; rumours of infidelity; speculation about Kate's whereabouts followed by news of the ill health of both her and the king…

Even in media and culture, there were blows at every turn, from Phillip Schofield's indiscretions and Holly Willoughby's fall from grace by association, to the devastating revelations that national treasure Huw Edwards had indecent images of children on his phone. Harry Potter went from a source of national pride to a national embarrassment as JK Rowling steadily beat her own legacy to death with increasingly transphobic rhetoric. Hell, I still haven't recovered from the loss of Mel and Sue from the Great British Baking Competition – or its move from the BBC to Channel 4 in 2016.

Perhaps the plummeting British propensity to boast about our history is a sign of hope

Our beloved but beleaguered NHS is on life support; our public transport system remains both blindingly inefficient and outrageously expensive. And in recent years the cost of living crisis has festered on all this, causing small businesses to close, putting pressure on the nation's pockets and making every aspect of life a little greyer, drabder and harder. The news that Wilko was to close last year was, for me, the final straw.

But the biggest collapse of pride has come in relation to Britain’s history. Here, at least, there are some obvious triumphs to hold on to. World War II, for a start: Churchill’s stirring “we will fight on the beaches” speech; a country united to defend freedom against fascism; victory in the face of an abominable evil that would change the course of all our histories. Could it be that we have become less interested in this crucial point almost 80 years later? Or have we simply grown tired of the chauvinism referenced in so many films, books and plays, and now used almost exclusively by “proud to be British” nostalgics who use their supposed patriotism as a flimsy cover for racism?

Perhaps, then, the plummeting propensity of Britons to boast about their history is a hopeful sign. It has been a decade in which the uglier facets of the country’s history have come to the fore. The fact that much of Britain’s power and dominance between the 17th and 19th centuries was derived from slave labour and colonialism – and the extent to which Britain plundered its wealth from countless countries – is finally being openly acknowledged rather than swept under the carpet.

In 2020, a statue of slave trader Edward Colston in Bristol was torn down, desecrated and pushed into Bristol Harbour during Black Lives Matter protests. That same year, the National Trust published a report revealing that more than 90 of its properties have connections to slavery and colonialism, shedding light on their reality. “To be very clear, we are not making judgements about the past, what we are trying to do is reflect as accurately and fully as possible the histories of a variety of places,” John Orna-Ornstein, director of culture and engagement, said at the time.

It could be said that it is no bad thing that Britons’ patriotism has declined as they have faced up to the sins of the past, and it goes hand in hand with our growing acceptance of diversity. According to NatCen research, the percentage of people who think it is important for someone to be born in the UK in order to be described as “truly British” has plummeted from 74 per cent in 2013 to 55 per cent in 2023. The proportion who think it is important to have British ancestry in order to be considered “truly British” has fallen from 51 per cent to 39 per cent.

If racism, prejudice and xenophobia are really declining, well, that really… is Something to be proud of.