F“Fourteen people texted me today,” I smile at my mother. “I just counted.”

I was 15 years old and had inherited my first phone a week earlier: my father's old Nokia 3310. Over the next seven days, I became obsessed with accumulating more and more numbers in my phone book. I asked everyone and everyone, not worrying if I would ever need, or even want, to talk to them. Almost 20 years later, my clunky Nokia is now an iPhone, I no longer save every number with “the more friends you have, the happier you are.”

Throughout my twenties and early thirties, I made it my mission to make friends with everyone I encountered after my high school friend group dispersed. I felt that if I could return to the protective arms of a tribe, I would feel at peace.

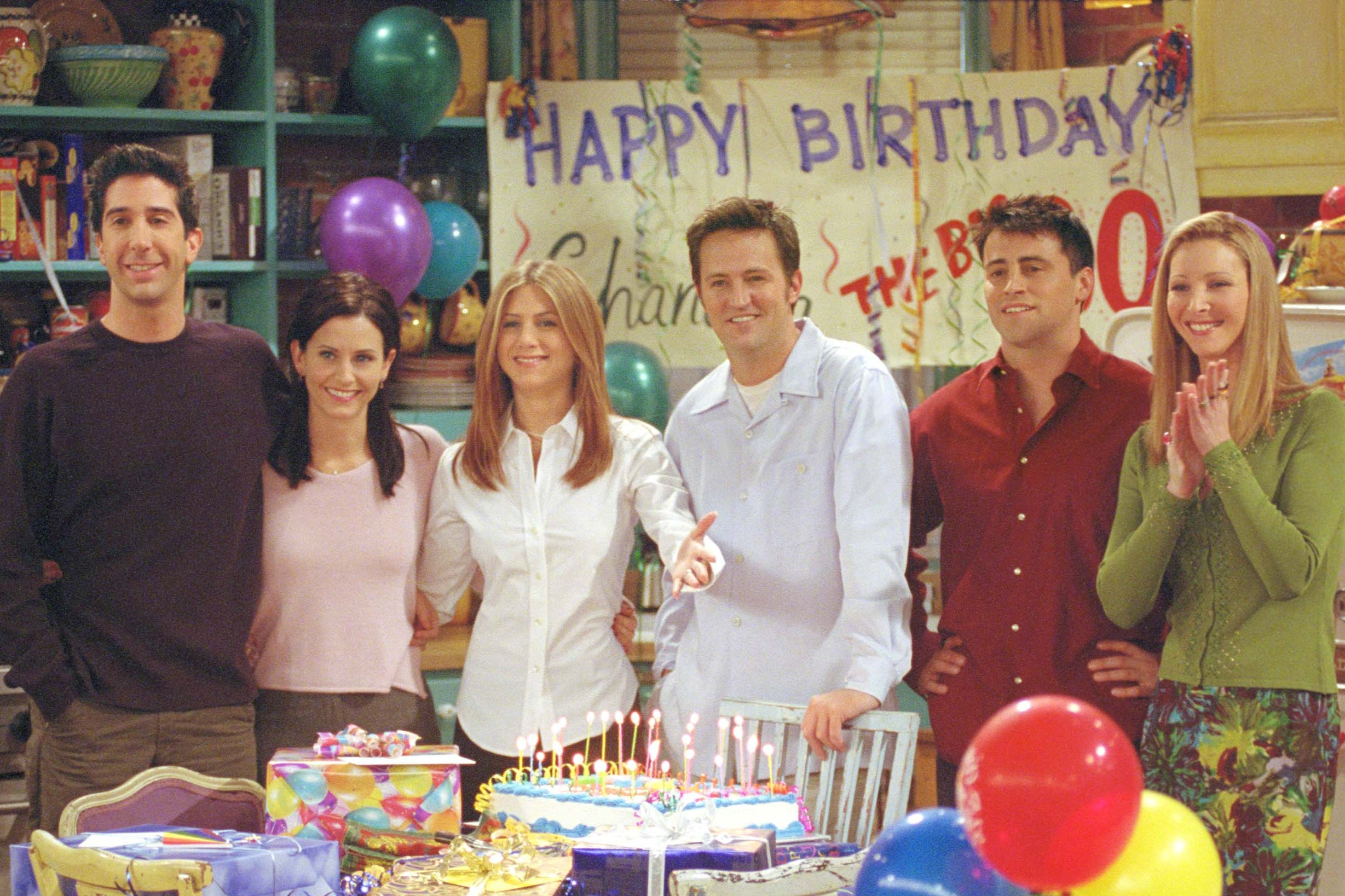

The thing is, while I felt like I had the equation figured out (more friends equals more happiness), I found that the immediate feeling of having made a new friend was short-lived, only to be replaced by an underlying, familiar feeling. feeling of not belonging. And then I would renew my determination and double my efforts, certain that I was only a handful of new friends away from achieving ultimate satisfaction. I never got there. Instead, I came to a place where I found many of these hastily acquired friendships to be exhausting, boring, and anxiety-inducing; the opposite of the way social media often depicts large groups of friends (invariably portrayed laughing and loving life en masse). Ironically, the more I got into other people's lives, the less sense of community I felt. I was juggling a full social calendar that left me feeling empty, trying to hold on to my plethora of friendships like they were hot potatoes in my hands.

And while I knew something was wrong, I wasn't clear on what exactly it was until I discovered evolutionary psychologist Robin Dunbar's findings on friendships. Based on research conducted in the 1990s, he determined that the optimal number of friends a person can have is five; Less than this and we are prone to loneliness. But interestingly, beyond this, our happiness also begins to decrease. We do not feel, as I had believed for 30 years, more worthy for the number of our friendships, nor does that guarantee a sense of community, and striving to maintain a wide circle of friends becomes less viable and, indeed, valuable. the older we get.

Dunbar's study recently resurfaced due to its mention in Elizabeth Day's book. addicted to friendship, and (along with Day's brilliant, deep dive into friendship and why she herself became so addicted to friendship) revealed to me a surprising and totally enlightening truth: your happiness does not increase with the number of friends. In fact, the opposite can happen. To some, this might have been obvious from the beginning. For others, it might be the same revelation (and indeed, relief) as it was for me. My question then was, why? Why was I obsessed with making friends when fewer, more deeply connected friendships could bring me more satisfaction?

“People are highly influenced by psychological drivers that make us seek validation and social connection,” Railey Molinario, an award-winning relationship intelligence expert, tells me. “Evolutionary psychology suggests that our ancestors depended on social groups to survive, providing them with protection, shared resources, and a better chance of thriving. This deep need to belong persists, making us believe that having more friends will give us more support and security. Childhood experiences also shape our desire to have a large social network. Early social interactions and reinforcement of social norms influence our perception of friendship and social success.

“Having more friends can lead to superficial connections instead of deep, meaningful relationships,” he continues. “As the number of friends increases, the time and energy available for each relationship decreases, leading to weaker bonds and less emotional satisfaction.”

Molinario explains to me that relational intelligence emphasizes the importance of authenticity over numbers. “Genuine friendships, where we can be ourselves and feel deeply connected, are much more rewarding than many superficial friendships. Additionally, the illusion of closeness created by social media can trick us into believing we have more meaningful connections than we really do.”

Psychotherapist Mark Vahrmeyer also believes social media is somewhat to blame for the “incremental shift” toward the idea that having more friends equals more happiness. “I think this is largely due to the commodification of relationships driven more generally by social media,” he tells me. “In many cases, the depth of friendship is sacrificed for the illusion of a connection driven by similarity of experiences, feelings or tastes. This would be the arc of immature relationships.

Recognizing what may be driving our need to make friends is the first step. Then ask ourselves if it is really about having more friends and if so, what is it increasingly giving us?

Mark Vahrmeyer, psychotherapist

“On the television show first dates, viewers can watch from the table as a blind date unfolds between two contestants of the show who have been matched. Psychologically mature people will generally be curious about each other and foster a sense of connection by sharing information about themselves that the other then receives, digests, and responds to,” Vahrmeyer continues. “There's also a teen version of the same show and what stands out strongly is how many teens will be looking for a sense of 'identity' with their quote: 'Oh, you like Star Wars, so do I!' – as if this were evidence of compatibility in relationships. This is what I mean by immature relationships.

“Combine this immaturity with an increasingly consumer economy where success is flaunted on social media through the accumulation of desirable products as evidence of wealth status and it is not difficult to see how more friends have come to equal more success.” .

I explore more. I want to know because there was such a specific number when it comes to the “perfect” amount of friends and more. Why five? “Dunbar's research suggests that humans can maintain stable social relationships with about 150 people (that is, people who recognize us 'on sight'). Within this broader circle, having around five close friends represents our most intimate and trusting relationships,” explains Molinario. “This number is significant because it allows for deep and meaningful interactions without overwhelming our emotional and cognitive resources. The authenticity of friendship is crucial; Having some genuine relationships can be more satisfying than more superficial ones.”

And Vahrmeyer emphasizes that relationships “cost us time and energy” and, therefore, that investment can only return us happiness or satisfaction if we consider it worthwhile and sustainable. “Some relationships are purely transactional, like business relationships, for example. There is a return, but it is not about connection, at least as a primary goal. However, I wouldn't consider them friends.”

Both experts maintain that the figure of “five” should be taken as a rough guide, since each individual's optimal friendship number will vary slightly (although not enormously). Vahrmeyer suggests that the key to finding our number is understanding our own needs and the reason behind our need for more friends. “If having more friends is driven by the fear of missing out and/or the need to succeed by having more friends, then we will invariably expend energy on these 'friendships' without a real connection.

“Recognizing what may be driving our need to gather friends is the first step. Then ask ourselves if it is really about having more friends and, if so, what does it increasingly bring us? he says.

The illusion of closeness created by social media can trick us into believing we have more meaningful connections than we really do.

Railey Molinario, relational intelligence expert

And if you are reading this thinking: “But I don't have five friends.” – psychotherapist, author and founder of The Purpose Workshop, Eloise Skinner, urges not to stress: “It's really an individual journey to see what works for you. I would recommend that people don't get hung up on a number (thinking, 'I just need to get three more close friends before I reach the optimal level'): it can get a bit transactional. Instead, check in with yourself as you maintain and develop your friendships. Be honest with yourself about which friendships give you energy, comfort, and inspiration, and work to develop and support them.”

My painful realization is this: it was never about having more friends (although this may not surprise some of you). In reality, it was about collecting reasons why I was valuable; about trying to raise my own self-esteem. Surely, surely, I had unconsciously reasoned, the more people like me, the more likable I must be. My quest to accumulate friends could have been replaced by an insatiable appetite for making money, collecting prizes, or acquiring cars. For me, it was just about people.

Because the truth is, despite all the numbers exchanged, the coffees drunk, and the party invitations shared, if I looked at my phone book and counted the number of friends with whom I felt I could be completely myself, who I could trust without a doubt and with those who made me feel energized and calm at the same time, there are probably five. And each of those five adds more value to my life than the rest of my phone book combined.

So maybe my true number, my happiest number, is six: five close friends plus one very good therapist.