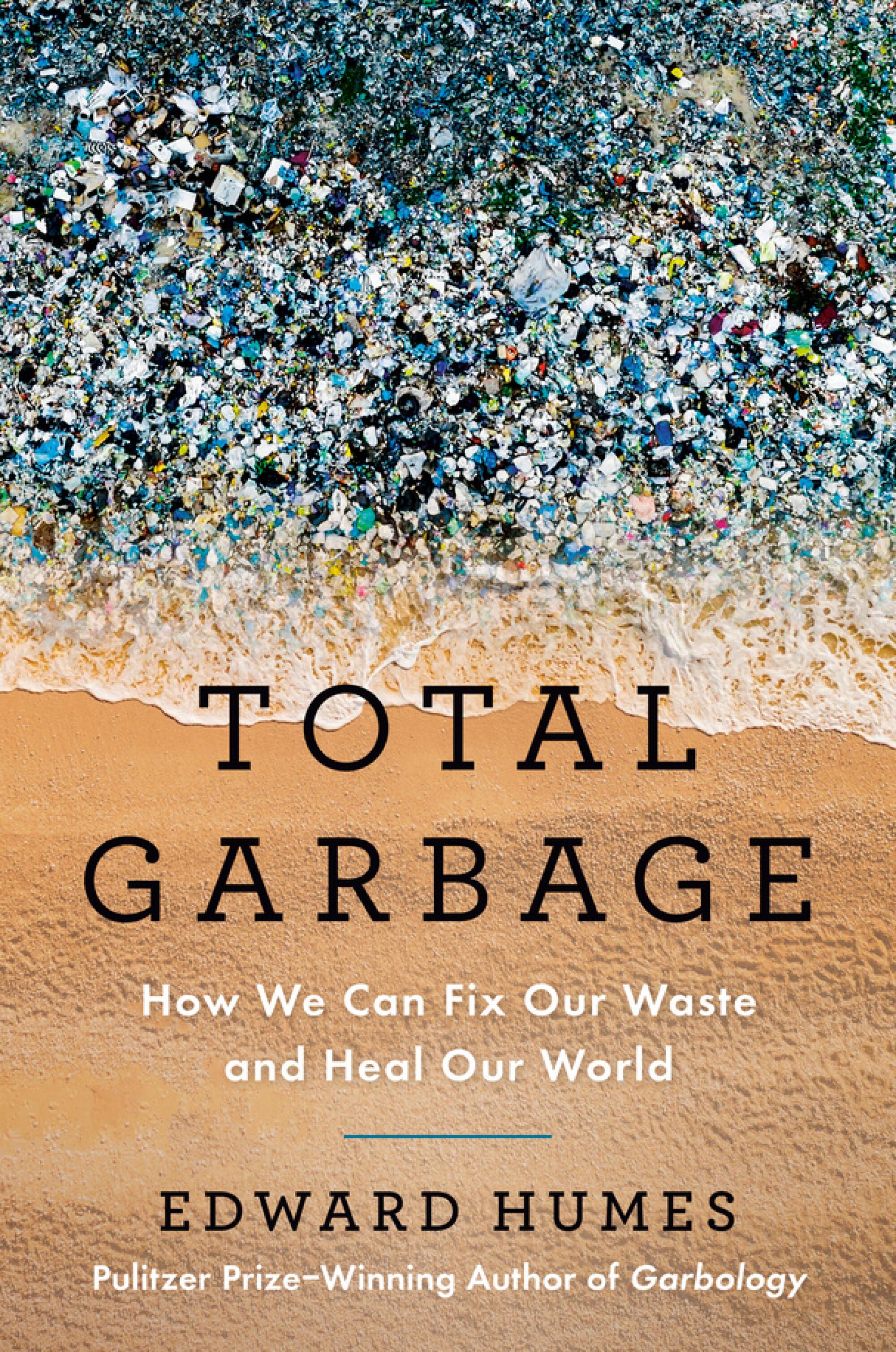

Edward Humes thinks a lot about trash and how we should deal with it. “Garbology,” the Pulitzer Prize-winner’s book about “our dirty love affair with trash,” was published in 2012, and “Total Garbage: How We Can Fix Our Waste and Heal Our World” was published earlier this year. This interview has been edited for clarity and brevity.

I hope you can talk about Ridwell, the subscription service that focuses on reusing or disposing of hard-to-recycle items and inspired an episode of “Total Garbage.”

HumesWe lived in Seattle for about three years. Right around that time, Owen's List, a father-son project, was morphing into what Ridwell is today.. Ryan Metzger's 7-year-old son, Owen, came home from school one day and said, “We're learning about recycling. What about this bag of old batteries in the drawer?”

They knew they shouldn't throw them away, but there was no easy way to do it, so Ryan called around to a few neighbors and found a place to take them. They asked neighbors if they had any old batteries that they could recycle or dispose of properly or transform into new materials in a proper way. And that became a reality, a father-son project.

[The collections expanded to include light bulbs, electronics, plastic bags and Halloween candy, and Owen’s List eventually morphed into Ridwell. Customers get a Ridwell bin and bags for collecting various items, which are picked up biweekly. Hard-to-break-down plastics usually have to travel farther to manufacturing plants that use them for outdoor structures such as decking and fencing and long-lasting drainage products. Prices start at $18 a month.]

When I met Metzger, one of the first questions I asked him was, “So once we get past Seattle, which is known for its citizens’ commitment to green and climate action, how is this business model going to work when you’re asking people to give up two or three lattes a month just to have their trash managed more responsibly?”

He said, “Well, we consider it a success when we get 15% or 20% of a postcode, and we can live off that, no problem. And we think we can do that.”

Metzger has been proven right. All of the communities they have expanded into since Seattle seem to be working for them. They are in Atlanta and in Minnesota, in the Twin Cities. Of course, Los Angeles is the big kahuna now. They are here.

When I first read about it, I thought, “At this point, I should shame municipal governments into adopting the model.” But for now, who is likely to pay for the service?

Humes: It's surprisingly affordable, but we're sick of the $10 and $15 price tags, saying, “Oh, Hulu.” “Oh, my kids want Disney Channel.” “Oh, I really need that coffee, that overpriced latte.”

It's just one more thing, and it really does add up over time, so it's a lot to ask, really. You're taking the time to sort through things that you would normally throw into a bin that would end up in the landfill.

Ridwell, as you say, exposes the existing system because it has become a kind of intermediary. They are intercepting [trash] Before it ends up in the landfill or as plastic pollution that is half-recycled, which is what happens with most of our plastics. 6% is recycled in the US and 9% globally. You might as well not even bother trying.

The great thing about talking to Metzger is that one of the first things he said to me was, “Ideally, we would become obsolete one day. But right now it doesn’t seem like we’re on that path. In the meantime, we’re just doing what we can.” [Ridwell] He does many other things, like collecting old glasses and putting them in the hands of homeless people.

“Total Garbage” has an episode set in the state of Maine, where a resident came up with an idea that I’ll call “let’s make the producers pay for it.” How did it work?

Humes: Maine is the first state to adopt what might colloquially be called an extended producer responsibility (EPR) law. The idea is that if a product causes harm to the environment, fixing that problem — either by fixing it or paying for the harm caused — should not be the responsibility of taxpayers or ratepayers, but of the producers who created the problem in the first place.

The idea in Maine is very simple, but it took eight years for one person, Sarah Nichols, then of the Maine Natural Resources Council, to make it a reality. Again, it was another triumph of one person with an idea, convincing other people in one community at a time to adopt it and work with her to make it a reality.

She is a young, outdoorsy single mother with an interest in sustainability. Her proposal was simple: “Hey, I make my kids clean up their room when they make a mess. Why don’t we have these kids clean up their mess?”

It's interesting that this happened in Maine.

Humes: Maine has a citizens' legislature, and its members work part-time. They are not professional politicians. In other words, the leader of the Republican Party in the state legislature is like a career lobster fisherman. But he, too, has joined this idea.

Ridwell co-founder and CEO Ryan Metzger came up with the idea after organizing a local effort in his neighborhood to collect and dispose of hard-to-recycle items.

(Ridwell)

The idea is to require disposable packaging and containers to be genuinely recyclable, rather than theoretically recyclable. If manufacturers and producers are required to pay for this, they either have to create materials that are genuinely recyclable or they have to resort to reuse, which is really the goal Sarah hopes to achieve. Otherwise, they will add a huge new cost to their operating costs, which they will not be able to pass on to consumers.

Sarah was very astute. In every community she visited, she would find a local person who was a prominent member of the community or a local leader of some kind, or just a really passionate citizen who was willing to participate in the community governance process. That kind of local influence supporting a new idea, rather than someone from the outside, makes a huge difference in any community, but particularly in Maine, where a lot of people know each other in these towns, and she started to gain ground.

A big achievement for Sarah was meeting with the founder and CEO of the most popular craft brewery, Allagash Brewing, in Maine, where they like their beer. And he told her: “We are the ones who created this problem and we should help solve it. I will support this.”

That was a milestone. That's why there was bipartisan support for this particular bill: because it made sense.

Has anyone asked you to try to export the concept to another state?

HumesAbout 30 states immediately wrote and asked for copies of the legislation. Other states have adopted similar programs. None of them have gone into effect yet, including Maine, because it takes years to develop rules and create a management organization. And, of course, lobbyists are fighting to water it down with each new version.

I'm sure the big fear of the fossil fuel industry, which sees plastic as a way to expand its customer base, is that the EPR principle could be applied to almost anything and should be applied to almost anything.

Let’s talk about Morris, Minnesota, the subject of an episode titled “Schooled.”

Humes: Let me set the scene. Morris is a town of just over 5,000 people (the county seat) with generations of farmers. It's a very rural area and politically it's quite conservative. But over time it's developed a relationship with the University of Minnesota campus in Morris, which has about 1,500 students. It's impossible to miss the place when you're miles away because of the two huge wind turbines on that campus.

What attracted me to Morris was what seemed like an unlikely partnership between the university and Morris County farmers, which began with a food-agriculture composting operation.[ricultural] waste.

Farmers had been discouraged from going full-time into composting because it's too cold there and you need very expensive equipment. But apparently no one gave that message to the students at the Morris campus because they said, “Oh, we could do that.” And they started their own composting program on campus.

It was so successful that they started receiving material from all over the community. Suddenly, they had a countywide, student-run, volunteer composting operation up and running, and farmers were getting all that great compost. They were getting rid of their organic waste without having to pay landfill fees.

Finally, after several years, the students donated what was now a prized program to the county and said, “Take it over. We want to keep this going. We’re graduating, but there’s no reason it has to die with us.” And it continues to run to this day.

It was a “these kids are doing okay” moment for locals and led to a conversation between the city and the campus’s sustainability director, a man named Troy Goodnough.

He [asked] about other ways the city and university could collaborate. One of the things they told him was, “Well, our budgets are tight and our electric bills are killing us. We saw you were doing something there.”

Years before it became fashionable, the campus had adopted LED lighting for both exterior and interior, saving a lot of money. That's why he said the university could help the city.

(Worradirek/Getty Images/iStockphoto)

So with a little bit of technical expertise, some grant writing support, and connecting people in the city with people who knew what they were doing in this space, they were able to get funding and support to make that conversion.

By the time they were done, the city was saving about $100,000 a year, which, for a small city budget, was the difference between being in the black or being in the red and being able to afford to do other things.

None of this had to do with climate change. It's about saving money, being more efficient, reducing waste. These are virtues that are as apolitical as possible.

The city also knew those wind turbines on campus made sense because they were big when they were built — about 1.65 megawatts each. They generate four times the power the campus needs, so the energy was pouring into the local grid and lowering rates for everyone.

They said, “Well, we don’t see ourselves building any wind turbines in our town, but what about solar? What about geothermal?” Now every public building in Morris has solar on the roof, even the liquor store. And the local school district got on board with electric school buses, and the town has buses that are electric.

You have shared many reasons for optimism in this conversation.

Humes: Yes, I would say so. Now that I've done this research, I'm more optimistic than I was before. I think creating a broader group that brings together communities that you wouldn't normally associate with taking action to prevent climate change is a very important thing.

I'm not pretending that it's not a problem. It's just about finding the motivation to get people on board with that idea. And I think we need to put in more effort than we're putting in. That was the point of the book, and I'm seeing evidence that we're doing that. are Doing that is simply not enough.