Truly support

independent journalism

Our mission is to provide unbiased, fact-based reporting that holds the powerful to account and exposes the truth.

Whether it's $5 or $50, every contribution counts.

Support us in offering journalism without agenda.

youUntil a week ago, I had never heard of Hannah Gavron. I now know that she was a pioneering feminist and sociology professor, whose work spoke to a generation of women desperate to break free from the stifling patriarchal conformity of 1960s Britain. But in some ways, perhaps my lack of knowledge was not surprising; her seminal book, The Captive WifeIt only gained traction posthumously, having been published just months after Hannah took her own life at the age of 29. Yet its portrait of women struggling to balance their careers and aspirations alongside motherhood still resonates today.

Sixty years later, the relevance of Hannah's life and work struck a chord with actress Daisy Boulton when she was given a copy of A woman on the edge of timea book written by Hannah’s youngest son, Jeremy. “Her absolute confidence and life force, her joy for life, her desire to see it all through and achieve at a high level at a very young age… it felt quite similar to my own childhood and trajectory,” she tells me. “But what resonated was the things that come from the outside world and hit you; the bullets that come. I think that’s what happens to girls and women who are very confident and strong – they take a lot of bullets for being that way. It gave me a strange comfort to be reading about this in such a raw way about someone, because I felt that rawness about my own experience.”

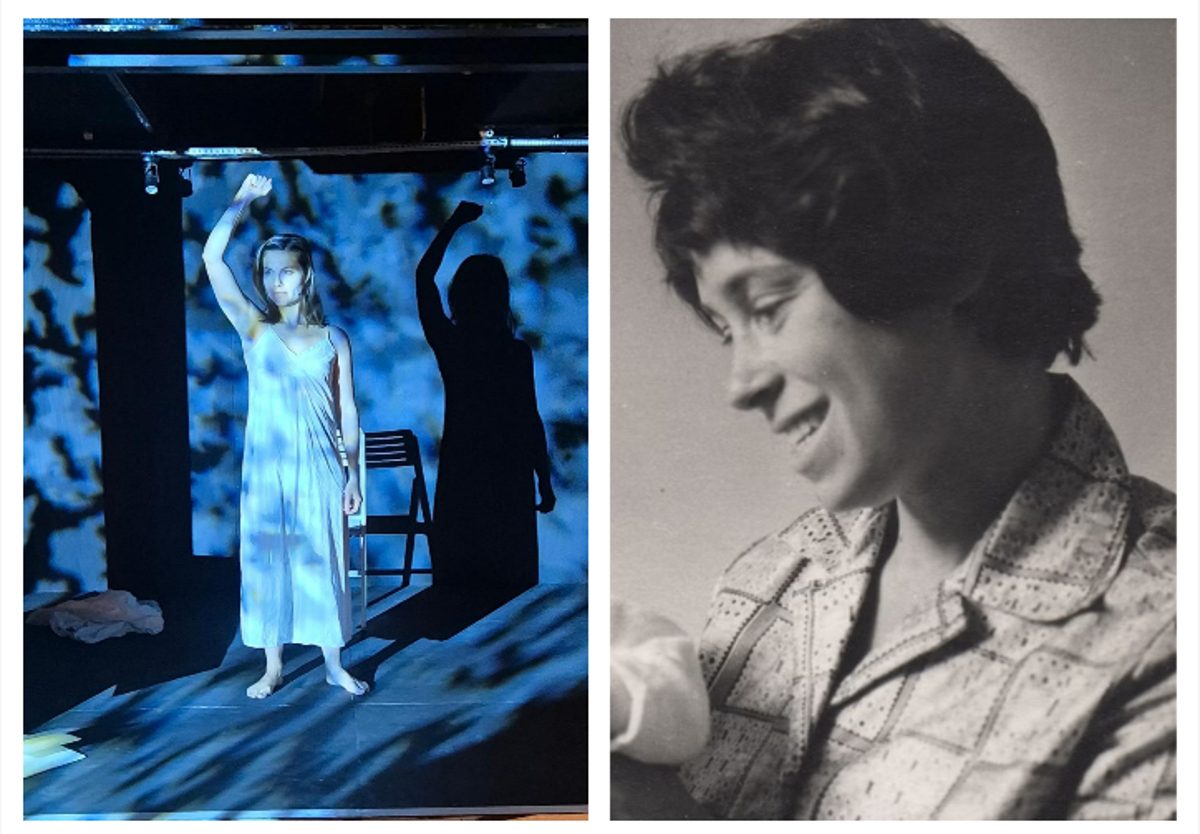

Boulton, whose credits include Shakespeare in love in the West End, she was so struck by this lightning bolt of connection that the book inspired her own interpretation. She will perform Time limita one-woman musical that depicts Hannah's life in parallel with that of a modern woman also on the brink and struggling to get through it, at this year's Edinburgh Fringe.

The book that inspired it chronicles Jeremy Gavron’s quest to discover more about his powerful Palestinian-born mother – both her life and her untimely death when he was just four years old. Through meticulous research, speaking to Hannah’s old friends and acquaintances and trawling through her letters and diaries, he seeks difficult answers to difficult questions. Who was this woman as a person? Why did her father refuse to talk about her after her death? And why did she end up feeling that suicide was the only option?

It is hard not to be reminded of Sylvia Plath when reading Hannah's story. Both were born in the 1930s; both married, a year apart, in the 1950s; both became mothers and had two children; both were brilliant, intelligent women, bursting with talent and potential, trapped in a man's world that constantly demeaned them and put up barriers. And both ultimately decided to take their own lives, just two years apart: Sylvia at 30, Hannah at 29. Even this they did in a strikingly similar way: both locked themselves away and turned on the gas oven in flats just a couple of streets away from each other in north London.

But there is one big difference between the two women – one that perhaps, more than anything else, motivated Jeremy to vigorously investigate his mother’s story. Sylvia’s suicide did not surprise those who knew her; Hannah’s did. “The coroner said it was the most baffling case of suicide he had ever come across,” says Boulton.

The coroner said it was the most baffling case of suicide he had ever come across.

There was little sign that Hannah was about to make such a devastating decision. She had always been bright, precocious and ambitious, having studied acting at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art (RADA) before dropping out to marry the future Labour Lord and publishing magnate Bob Gavron at 18. She was no typical housewife, however, having earned a first-class degree in sociology followed by a PhD.

At the time of her death, she was in a job she loved, teaching at Hornsey College of Arts and Crafts; she was soon to publish her first book; she had two young children whom, according to a suicide note Jeremy discovered 25 years later, she “loved terribly.” But according to her son’s hypothesis, Hannah was born in the wrong era.

“I’m clear that this particular moment in history was, in some ways, toxic for this particular person,” he said. The Guardian When her book was first published in 2015, Hannah said: “She was a woman who needed to realise herself in the same way that men realise themselves. I think the trouble she got into was that she got too far ahead of herself. She left other women behind.” She left men behind, too. Towards the end of her life, she had become estranged from her husband and was pursuing a doomed relationship with a colleague who was already in a relationship with another man. According to diary entries written by Hannah’s father, TR Fyvel, she was “struggling with her identity as an individual” and could not stand a husband who tried to “dominate” her.

A darker male presence also made itself felt much earlier in her life. When Hannah was still at school, she had what she described as an “affair” with the headmaster, a man Jeremy refers to only as “K” in the book. “K was after me,” she said. “What he did to Hannah may have made her vulnerable at 29. Every psychologist will tell you that.”

Another possible clue to her tortured mental state lies in her book, an extension of her doctoral thesis, which told the stories of the lives of married middle- and working-class women in Kentish Town. The Captive Wife Although her thesis received a lot of attention in 1966 and secured her a place in the canon of mid-century feminists who advocated greater independence and freedom for women, the road to publication was anything but straightforward. “It seemed like the last set of points – there were a lot of objections and blockages to the publication of her thesis,” says Boulton, who also studied at Rada.

Hannah would probably have reveled in the praise her work received had she been alive to see it: The Captive Wife The book has been called one of the “classic examples of a feminist understanding of housework,” while Hannah herself has been called an “optimistic pioneer of modern feminism.” And, although it was published more than 50 years ago, the message remains surprisingly relevant to women trying to juggle childcare with work today. Hannah argued that motherhood stripped women of their independence, putting their ambitions and dreams at odds with the traditional role they were expected to play as mothers.

“It’s very revealing,” says Boulton, “because all these women were saying, ‘Yes, I love my children, but I also feel like I want to do other things. ’ The general conclusion was that women feel restricted when they become mothers and want to work, and they’re not taken seriously. A lot of my friends who are now mothers also talk about this feeling of isolation. It still seems very relevant.”

Hannah's conclusion was that we needed to change the way society was organised for women, so that it would be easier for them to go back to work; she argued that if we created a system in which life with small children was no longer so completely different from life without them, motherhood would cease to be a kind of bondage. The changes she was demanding, the views she was expressing, seemed as if they had been published last week or last century.

But Hannah couldn't change the society she lived in, and that apparently made her wonder if… sheIn fact, the problem was whether she It was he who needed to change.

You can really see the moments where she starts to question herself, and it feels like she's drifting away from her North Star.

Reading Hannah’s letters, “you get a real insight into her,” Boulton says. “You can see the moments where she starts to question herself and seems to be drifting away from her North Star. The main theme was this conflict: between conforming to societal expectations and pressures as a woman and following her wild, true longing as a big, bold, brilliant woman.”

And so Boulton feels compelled to pick up the baton of Hannah’s story, to channel her predecessor’s energy and candour into a world where women who are unapologetically themselves can still feel woefully out of place. “It’s hard to be a full person,” she says. “I’ve had my own struggles throughout life and I’ve wondered how to be myself in this world. Being a strong, intelligent woman still doesn’t seem very easy to me.”

It may not be easy, but through her new take on Hannah’s story, Boulton wants to convey a message to other women: “Never stop being yourself in the world. Never lose your sense of true identity. Be brave enough to be yourself.”

Daisy Boulton is performing ''On the Edge of Time' at Underbelly (Belly Dancer) in Edinburgh as part of the Fringe from 1 to 25 August 2024