In 1994, Eric Nakamura launched a zine he called Giant Robot, a fan's photocopied and hand-stapled ode to manga, anime, Japanese punk bands, and skateboarding. Thirty years later, what began as the personal hobby of a self-proclaimed outcast has morphed into a bastion of pop culture centered on Asian American and Asian artists.

Eric Nakamura gives a tour in front of an artwork by Sean Chao titled “Robot” at the Japanese American National Museum.

(Michael Blackshire / Los Angeles Times)

With “Giant Robot Biennial 5,” which will be on display at the Japanese American National Museum through September 1, the West Los Angeles native looks back on his DIY days and showcases the creatives who have been a part of his artistic ecosystem from the past to the present.

The collective exhibition presents the ceramist taylor leeFigures inspired by old Japanese sci-fi movies, as well as Lucas Chuehthe iconic haunting bear paintings and a graffiti installation of Mike Shinoda of Linkin Park fame.

“I thought, 'Okay, art has to reflect this 30-year journey,'” Nakamura said of curating the exhibition, which ranges from multimedia works by a long-time collaborator James Jean to small but powerful watercolors by emerging artists Rain Szeto.

“I used to hate looking back. I always thought, 'What I'm doing now is the most important thing.' But for the first time I went through all the files, all the photos in jars and jars of hour-long photo envelopes, and started organizing them. And I think it was just a good kick in the butt to understand: How exactly did I start over? I immersed myself deeply in doing this exhibition.”

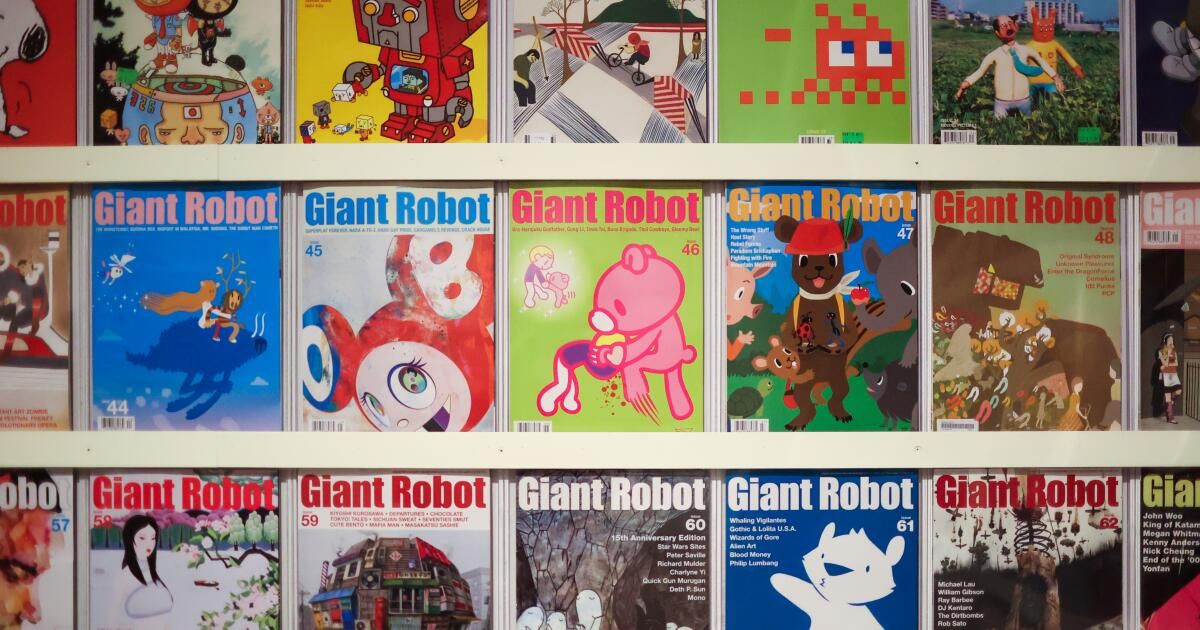

When the biennial opened on March 1, more than 1,000 fans endured a labyrinthine line to glimpse the scraps of paper, scissors and glue sticks used to make the first magazine. They examined a collage of candid photographs trying to identify the stars who orbited Giant Robot in the late '90s and early '00s, from comedian Margaret Cho to rocker Karen O. And they posed for selfies in front of a wall covered with issues of Giant Robot magazine, the now-defunct magazine full color. glossy that evolved from the magazine and featured a cover by people like Takashi Murakami and Yoshitomo Nara. (The cult-favorite bimonthly magazine, which Nakamura edited with his friend and former colleague Martin Wong, closed in 2010 after 68 issues.)

“Giant Robert Cover” by Felicia Chiao, framed and displayed at the Japanese American National Museum.

(Michael Blackshire / Los Angeles Times)

In the gallery's other rooms, guests eagerly awaited their turn to interact with artists who began as Giant Robot fans and eventually launched their careers by exhibiting at Nakamura's. Neighboring retail store and art gallery, GR2on Sawtelle Boulevard in Japantown.

Felicia ChiaoThe San Francisco-based illustrator behind the biennial's fantastical, bubbly promotional art credits Giant Robot for her entry into the art world: “In 2020, [Eric] He gave me my first solo exhibition. “I wasn’t familiar with how galleries worked and I had no community at the time.”

One of his contributions to the show is a charmingly chaotic depiction of the busy Sawtelle block. Nakamura used that same image as the cover of his next book, “Giant Robot: Thirty Years of Defining Asian American Pop Culture”, which falls in September.

“It is very encouraging to see AAPI [Asian American and Pacific Islander] artists thrive and succeed, and this shows others that it is possible,” Chiao said. “No matter where my career goes, I believe I can always return for a sense of community and belonging.”

Biennial participants used the words “community” and “family” when talking about their working relationships with Giant Robot. In fact, Yoskay Yamamoto, whose serene paper mache and wood installation “Moonage Daydream” is at the center of the exhibition, said he met his wife at GR2 in 2017, proposed to her at the gallery five years later and recruited Nakamura to officiate at their wedding last year.

“In my mind, [GR2] it’s kind of like Whiskey a Go Go,” said painter Darren Inouye, who with his wife Trisha forms the Los Angeles creative duo. Giorgiko. “It's a small place; If people didn't know what to look for, they'd probably overlook it, but it has a huge legacy. Many legendary artists have passed through its doors.”

An artwork by Giorgiko, titled “Broken Sakura,” is inspired by Darren Inouye's grandmother's internment camp experience.

(Michael Blackshire / Los Angeles Times)

Giorgiko's contributions to the biennial reference the incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II and include two pieces honoring Inouye's grandmother, who was interned at the Santa Anita Assembly Center at age 14.

“I repressed my Asian side a lot growing up,” Inouye said. “I just wanted to be as 'normal' as possible. With Eric and Giant Robot, there was an element of a healthy amount of pride: not sweeping our ethnicity and history under the rug, but being able to highlight it.”

Eric Nakamura pauses to take a portrait in front of the covers of Giant Robot magazine.

(Michael Blackshire / Los Angeles Times)

In the early '90s, that was Nakamura's mission: to reach other “underdog” young Asian Americans who shared his interests but didn't see themselves represented anywhere in print.

“If you look at the first [zine] “Identity is a big problem,” Nakamura said. He added that although there were other Asian American students when she attended UCLA in the early '90s, “I still felt like an outcast there because I liked punk rock and I had long hair… and maybe I could have showered a little more.”

(To come full circle, later this year he will return to his alma mater to curate a multi-night film and television screening series celebrating Asian and Asian American artists at the Hammer Museum's Billy Wilder Theater.)

“Creating a scene is really where everything comes from.”