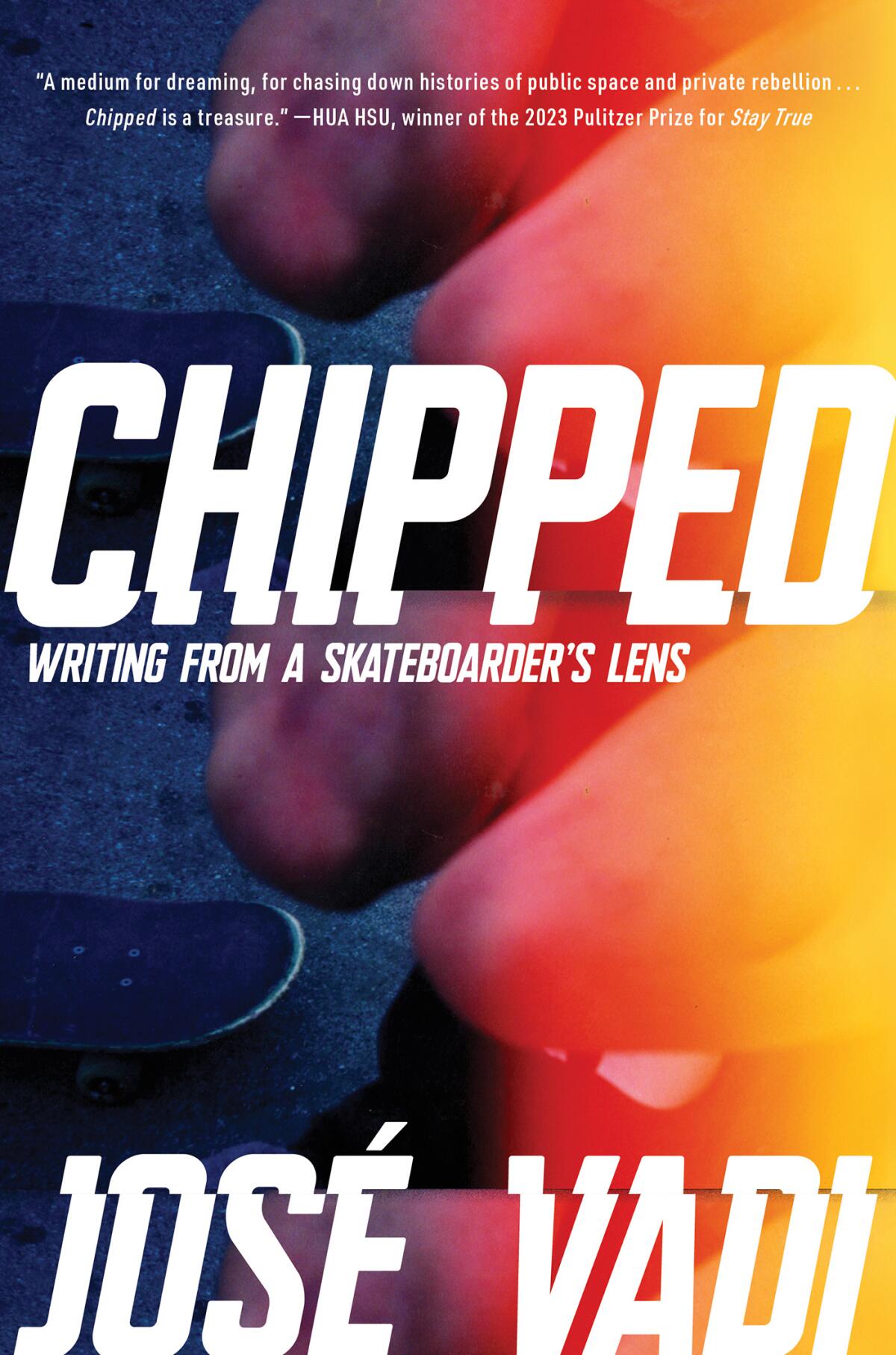

Book Review

Chipped: writing through the lens of a skateboarder

By José Vadi

Soft Skull Press: 256 pages, $26

If you buy books linked to on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

“Chipped: Writing From a Skateboarder's Lens” by José Vadi is, literally, a collection of essays. But it's also a map of Vadi's personal California.

From Pomona, where he grew up, to the Bay Area, where he lived until recently, “Chipped” charts the state's urban spaces as seen from the back of a board, a network of routes laid out block by block. Vadi's vision of neighborhoods is granular.

“I continued down Broadway and toward the bike lanes that connect Rockridge to neighboring Temescal, from 51st to 40th streets,” he writes of a skating session. “Responding to every creak, car, stop sign, smell and sound around me.”

The specific geography may not be familiar to all readers, but the mode should resonate with lifelong Californians. Joan Didion once wrote of her own home territory, around Sacramento, that “when we talk about sale-leasebacks and right-of-way takings, we are speaking in code for the things we like best, the yellow fields, the cottonwoods and the rivers. going up and down and the mountain roads closing when the heavy snow arrives.”

For her part, Vadi evokes the charms of California through descriptions of tantalizingly empty parking lots, perfectly wax for skating, dangerously designed intersections and the brilliant temptation of stairs and railings.

For Vadi, skateboarding is not just a sport or a hobby, it is “a discipline, a practice, a ritual.” It is also a portal that puts you in touch with the ungoverned and the unknown by allowing you to navigate the world on your own terms.

José Vadi, author of “Chipped: Writing From a Skateboarder's Lens.”

(Bobby Gordon)

That kind of exploration can be dangerous, especially if you're not white.

“When a dark-skinned child begins to ride a skateboard at any time, he enters a police world that presumes his guilt, accelerated now by the four wheels that propel him, sometimes illegally, through the city streets, the schoolyards. and the alleys,” he writes.

But the adventures that skateboarding facilitates can also be gateways to freedom and self-knowledge.

“Gonna [live music] Shows and skateboarding emerged for me at the same time, finding the spaces in the street and the places that mattered to me because I knew that each space contained a vision of the world,” explains Vadi. “Cities are invitations to parts of ourselves that we always knew but couldn't access without those introductions.”

“Chipped” It's as much about the art and culture surrounding skateboarding as it is about the act itself. Vadi remembers the music he learned from skate videos, as well as the videos themselves, compilations of the skaters' best tricks and, of course, some of their gnarliest falls. She mentions iconic footwear and clothing brands (Emerica, Dickies, Airwalk), as well as skate magazines, like Thrasher and Transworld Skateboarding, where she discovered what the best skaters were wearing.

Another facet of the broader subculture is the “skater lens” that the book's subtitle promises: a sense of radical self-sufficiency, a jaundiced gaze toward what constitutes “public space” and what is permitted in it, a familiarity with pain and a coldness led to danger.

But it's not enough to live that lifestyle; Vadi finds out that he needs to do something with it too. The book's final essay, “Programming Injection,” focuses on a short column of the same name that ran in Transworld Skateboarding in the 1990s. In it, skater Ed Templeton claimed that “documentation is domination,” and a young Vadi took it as gospel.

Skateboarding may now be an Olympic sport, but most of its practitioners still practice it on the margins, repurposing urban architecture for their own purposes. Its joys are often fleeting: a perfectly performed trick becomes iconic only if the moment can be captured, repeated, disseminated and shared. Skateboarding, as Vadi understands it, is an act of defiance, a story that is not normally written. Part of what makes his documentation powerful is proof that a life like this is possible.

“Chipped” bears the marks of everything Vadi learned on his board. His prose is often vivid and propulsive, and he describes “benches so waxed they were black slabs of ancient white concrete, generations of candles melted by the sun and ground into iconography.” Of course, his speed sometimes escapes him, as when he calculates that a skater's path is “carved by a body's response to space divided by the desire for direction multiplied by the need.”

Vadi goes to great lengths to make “Chipped” accessible to non-skaters, describing the basic trick mechanics as ollies and slaps. But if you're not familiar with the sport, it's best read along with some of the videos it cites, all of which probably exist somewhere on the original VHS, but can also be found, in all their lovely lo-fi glory, on YouTube . There you can see not only the mechanics of the tricks but also the remarkable integration of the skaters with their landscapes. Cars drive through gunfire and threaten to crash with the consequences of failed stunts; Pedestrians gape and sometimes get in the way.

In skating, Vadi found “a compass, a lens, a portal to the joy that can only be found by trying.” “Chipped” It offers the same thing even to those of us who have never been on a board.

Zan Romanoff is a writer and author of several novels for young people.