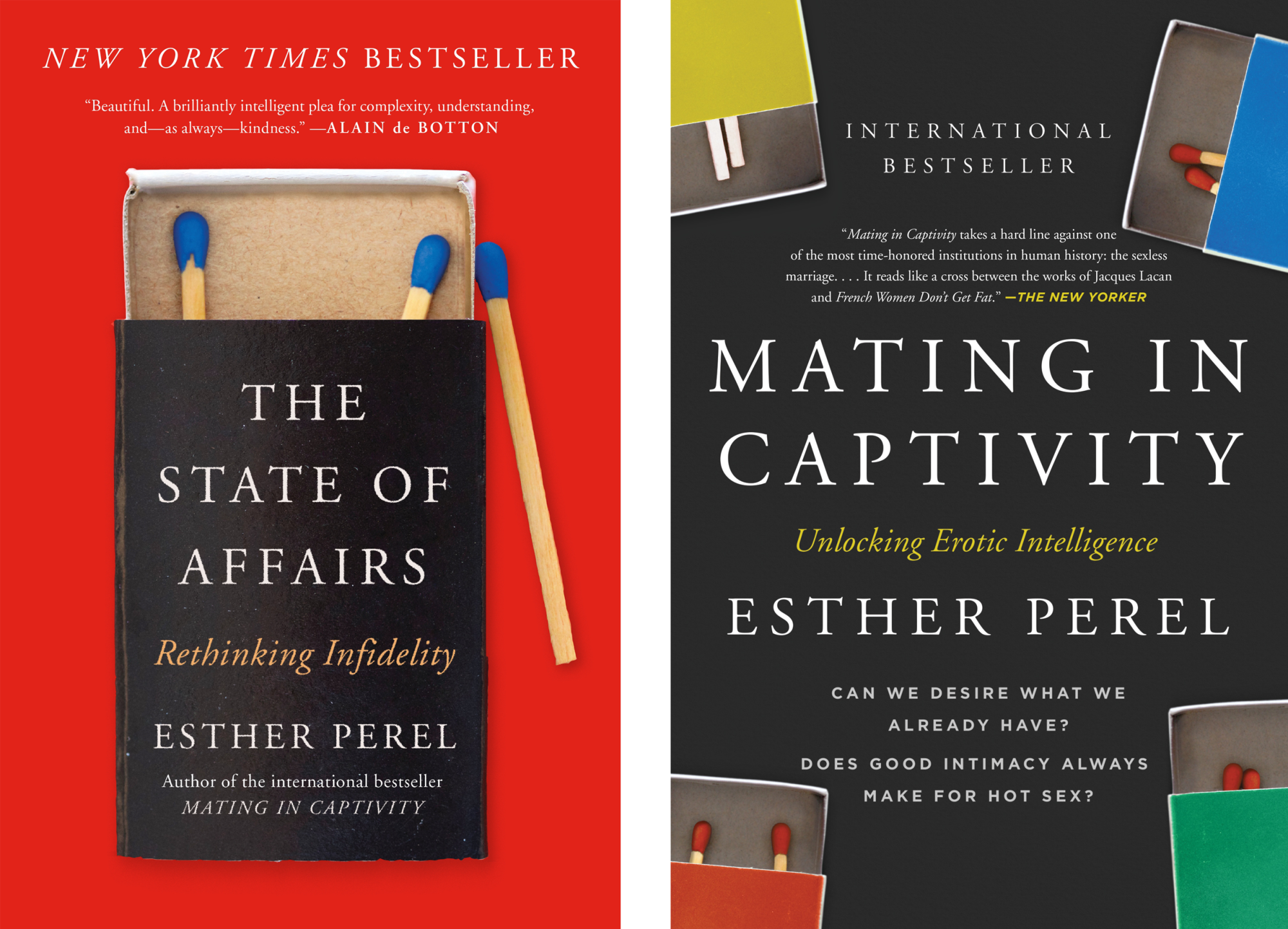

Esther Perel’s journey from psychotherapist in private practice to internationally renowned relationship expert is deeply intertwined with technology. It was her publishing presses that distributed her bestselling 2006 book, “Mating in Captivity: Unlocking Erotic Intelligence” (HarperCollins), in more than 30 languages. Videos of her subsequent hit TED Talks brought her theories about desire and stray glances to tens of millions of viewers (which she expanded upon in her 2017 book, “The State of Affairs: Rethinking Infidelity”). Multiple podcasts that extended Perel’s therapeutic practice far beyond a physical office. An Instagram account where Perel sprinkles bits of relationship wisdom into the feeds of more than 2 million followers. And, starting Sept. 17, two one-hour online courses designed to help people strengthen their sexual connections.

“Suddenly, you can reach people in villages on every continent,” Perel said. “That’s technology.”

Shelf Help is a new wellness column where we interview researchers, thinkers, and writers about their latest books, all with the goal of learning how to live a more fulfilled life.

But the same technological forces that have helped Perel’s ideas reach the masses have also begun to shape and intrude on modern relationships: We swipe into oblivion on soul-sucking dating apps, we ghost out of the lives of our romantic interests, and our smartphones tear us away from our partners at crucial moments of connection.

It is these disturbing phenomena that Perel aims to address in her most recent tour of the United States, “The Future of Relationships, Love and Desire,” which she will take to the YouTube Theater on September 10.

Ahead of her visit to Los Angeles, The Times spoke to Perel about Generation Z’s sexless reputation, the limitations of intimacy on online platforms and how public humiliation on social media can interfere in the bedroom.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

How do you think technology has changed the romantic landscape since you started writing about it?

Esther Perel (Katie McCurdy)

The predictive technologies that promise to free us from life’s inconveniences are also creating a situation where we are increasingly more anxious, not less anxious, because we don’t practice the things that actually make us less anxious: experimentation, encountering the unknown, dealing with uncertainty, the unexpected, dealing with the lessons we learn from bad decisions. That’s what makes us less anxious, not algorithmic perfection.

If you spend so much time with algorithmic perfections, you start to experience and create distorted expectations, and you carry those expectations of perfection over into your relationships with other people and become less able to deal with conflict, friction, and differences.

Many studies say that Generation Z has less sexwith fewer partners. UCLA survey According to a 2023 study, just over 47% of people aged 13-24 feel that most TV shows and movie plots do not need sexual content and want to focus more on platonic relationships. What do you think about this?

It's a symptom of something that's happening in society, in our changing culture. Technology is a part of it. Relationships are imperfect and unpredictable. Same with sex. And you're vulnerable and exposed, even. And by the way, sex is never just sex. Even if you're having casual sex.

So you're less prepared for the vulnerability, for the unknown, for the consequences, for the communication challenges that sex demands. If everything has to be negotiated, as it is in relationships today, and there's no longer some big religious or social hierarchy telling you how to think, you have to make your own decisions and choices.

In order to negotiate anything, you need to know how to communicate, and those very communication skills (the ability to deal with uncertainty and the unexpected) are precisely what are being weakened in the digital age. Sex is the messiness of human life, the bumps, the smells, the affection.

For me, this is one of the central questions for the future: how are we going to manage the messiness of human life? That is the opposite of algorithmic perfection.

But the issue isn't that Gen Z wants less sex. They want less sex because they're more isolated to begin with. They have fewer friends. They don't go out, they work alone all day. You can go on an app, you can hook up, and after a while, that gets a little boring for some people. So it's not the sex, it's everything that's intertwined with sex.

Do you think it is possible to foster the kind of intimacy you describe on digital platforms?

“The State of Things” and “Mating in Captivity” by Esther Perel.

Yes and no. It allows many people to know themselves in ways they never would have been able to know. But I think this is emotional capitalism, where you have a thousand options at your disposal, where you participate in a frenzy of romantic consumerism, where you are afraid to commit to the good because you are afraid of missing out on the perfect.

We find ourselves evaluating ourselves as products, and that commodification has no soul. Do people meet on dating apps? Absolutely. I think 60% of people today meet online. But I think there will be a generational shift. There are more and more attempts by people who are done with apps to meet in person, even if it's speed dating, even if it's meeting in other circumstances, or even if it's to come to my show.

“Sex is never just sex. Even when you think it's a passing thing and shouldn't mean anything, the effort to make it mean nothing is meaningful.”

— Esther Perel

My most important message in response to this is: don't go on a date at a bar, at a restaurant, at a table face to face, that feels like a job interview where you're asked a bunch of stale questions that tell you nothing while you wait to see if you get butterflies in your stomach.

Go out and do something with your friends and take your date with you. Integrate dating into your life. You'll have 1,000 data points just by watching how this person interacts with people, how they answer questions, or how they make comments. But most of all, you're not isolating yourself, isolating yourself from your life to go play the lottery, lose, and then have to bring your shame back to your life, to your friends, to tell them it didn't work out. We can do better.

You've talked about how once you get into the bedroom you have to let go of political correctness, but we see a lot of online shaming these days related to that very topic. How do conversations about sexual politics on social media influence our personal intimate lives?

There are two questions in your question. One is: is a new kind of moralization emerging? And the second is: what is the nature of erotic desire?

I think of sexuality as a coded language, as a window into the self, into a relationship that demands deep listening, and that listening is that, in reality, sexuality is a coded language for our emotional needs, desires, fears, aspirations, and deepest wounds. That's why I always say: sex is never just sex. Even when you think it's something casual and supposed to mean nothing, the effort to make it mean nothing is significant.

In that sense, it's irrational. We don't fully understand why we like certain things. We don't fully understand why what I like is disgusting to you. We don't fully understand why that memory became a fantasy. We don't fully understand the inner workings of the erotic mind. The brain is a black box, but this adds another layer to your sexual fantasies. It's a uniquely human production that sometimes makes no sense because it challenges our values. It challenges our perception of reality. It challenges our perception of who we are as good citizens.

No one wants some of these things in real life, but if you turn them into a game, they can be very exciting, thrilling, and satisfying. And this goes even further when you delve into the world of kink. The erotic mind is often politically incorrect, meaning it is not governed by the standards of good citizenship that you yourself follow in the rest of your life.

But let's not be mistaken: nobody wants to be forced into anything in real life. Because when you play, you're not forced. There is no greater freedom than voluntary surrender. But “voluntary” is the essential word, so I say it very carefully. Because I know how tender and sensitive this is.

But that's one of the ways I've helped people make sense of their sex lives, their preferences, for over 40 years. Consent has become a central organizing principle, because consent goes hand in hand with desire. If desire is to appropriate desire, in order to appropriate it, it has to be consensual. Sometimes it's consensual, but not necessarily desired, because we can live with all kinds of contradictions within ourselves. I'm telling you yes, but I'm not really saying yes to myself, things like that. So consent is extraordinarily important, but it's not the only key element of sexuality. There are other pieces to this story.

CONCLUSIONS

By Esther Perel

Nowadays, we are ashamed of many different things. When I say that we have brought shame into the public sphere of social media, it is because this is not very different from the kind of puritanical thinking of “The Scarlet Letter” and the excommunications of all kinds that have existed throughout history. We have often, you know, exiled people in order to maintain our own moral superiority in various ways.

I'm not talking about people who deserve to be lectured or arrested for what they've done. I'm talking about how collective and sexual scandals have always been scandals that consolidated what was thought to be the moral fabric of the community that blamed you, scolded you or exiled you.

I know the breadth of your work can't be summed up in advice, but what do you want people to take away, to carry into their daily lives, from your speaking tour?

I’m not here to give you a lecture, I’m here to co-create a conversation together, and like the best therapy sessions, they don’t end at the end of the session. What matters is what happens next. It’s who you talk to, who you were sitting with and didn’t know an hour before. It’s who’s waiting for you at home that you should have a difficult conversation with. And if you can take me inside and bring me with you to the different areas of your life where you need some of that input, then I’ve done something meaningful.

This is something I say on tour and I say it in courses as well: relationships are stories. I'd like to invite you to consider your stories with a new curiosity, with more nuance and ambiguity. I want you to think about what parts of your story, relational and sexual, you want to keep and develop further, and what parts of your relational story you want to leave behind or change. That's my invitation.

(Maggie Chiang / For The Times)

Shelf Help is a wellness column in which we interview researchers, thinkers and writers about their latest books, all with the goal of learning how to live a more fulfilling life. Do you want to send us a proposal? [email protected].