YoIt may seem easy to foresee what a magazine mogul like Dylan Jones would include in his memoirs. Celebrity parties starring some of the biggest names in the business. Lewd stories about politicians and major media types. The real ups and downs of running a fashion magazine for more than two decades. You expect to laugh, stare, and cringe. What you don't expect, perhaps, is to cry.

This is what happened to me, I tell him. “Oh!” he says, more than a little surprised, as we settle into a meeting room in the offices of the Evening Standardwhere he has been editor-in-chief since June 2023, a major change from his 22 years as editor of British GQ. However, Jones' CV is not what moved me. Because beneath the glitz and glitz (all of which is there) are revelations about an incredibly abusive childhood and the revelation that he was raped at age 17, something he's never revealed before. In the book he confesses that he found the process of opening the page difficult. “All this seemed unnecessary to me, as if my father had beaten me,” he writes.

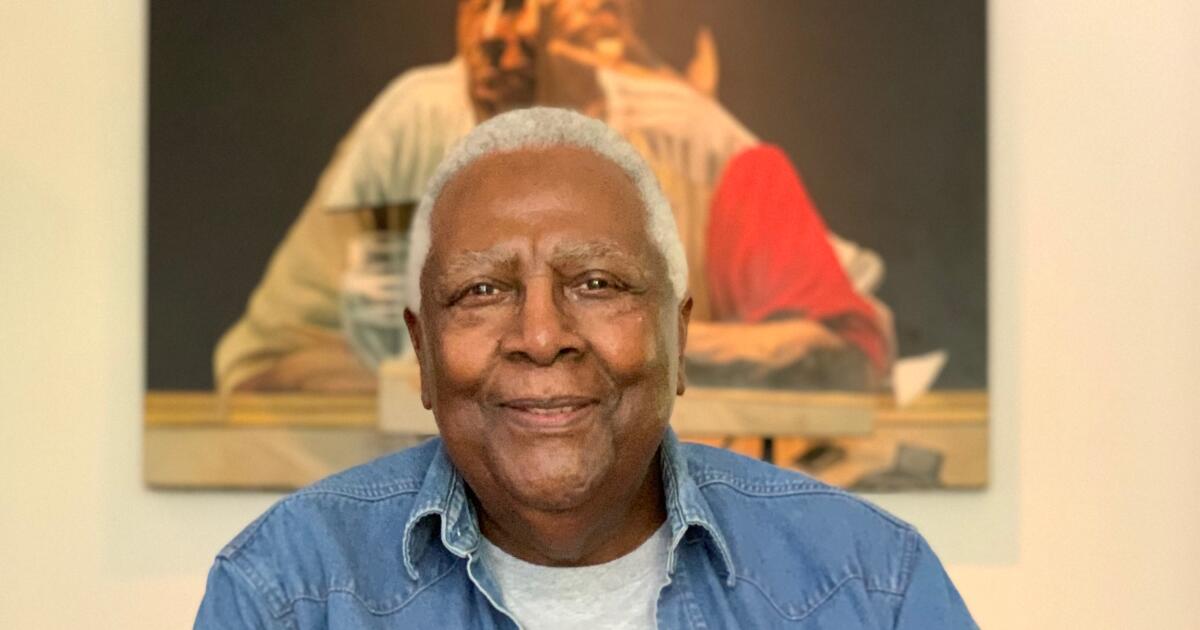

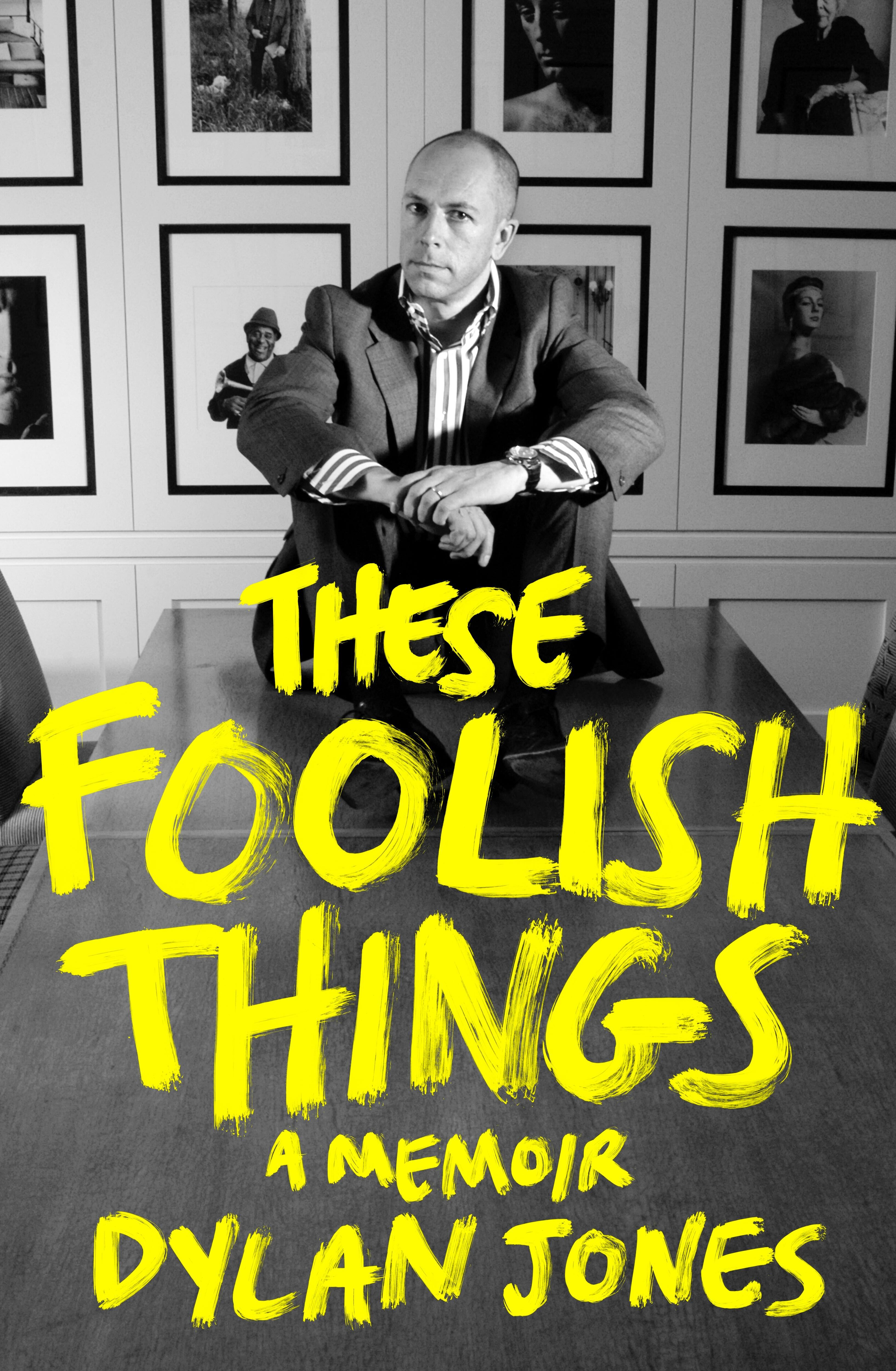

But Jones seems confused by my response, as if he didn't expect me to recognize the emotional elements of his book – or at least not at first. As the author of 27 other titles, Jones is no stranger to long-form writing. From David Bowie and U2 to Jim Morrison and David Cameron, the 64-year-old has covered a range of topics from pop culture to politics. However, writing about himself had never been part of the plan. “It wasn't my idea,” the 64-year-old says of the memoir he has written, titled These Silly Things. “When I left Condé [Nast, the publishing company that owns GQ], my agent suggested it to me and I said no. It didn't really feel easy because it felt a little bit, 'me, me, me.'”

Initially, the book featured very little about Jones's personal life. Only after the support of his family did she decide to open up. “It's something that doesn't come particularly naturally to me,” she says. Subsequently, most of the book focuses on his rise from Eighties club boy in High Wycombe to high-profile magazine editor. It is a journey that began somewhat fortuitously in 1983, after Jones had graduated from Central Saint Martins and had been “wandering around dead-end jobs”, one of which was selling sex toys in a Portobello Road shop.

Out of the blue, a photographer friend asked Jones if he could interview some people he was photographing for the counterculture bible. ID; Shortly afterward, editor Terry Jones offered him a job. The rest unfolds from there: four years in ID became a publishing house Sanda monthly men's title launched by Nick Logan, founder of Facewhere Jones also became a regular collaborator. Then came the transition to newspapers: Observer magazine and Sunday weather – and then went to [British] GQ. Here, she transformed the monthly title into a cultural juggernaut famous for its tongue-in-cheek covers (think Kylie Minogue recreating the famous Tennis Girl poster in 2000) and its annual issue. GQ Men of the Year Awards. Jones remained editor-in-chief until 2021, when Condé Nast announced it would merge its editorial teams as part of a new digital-first global strategy. Most of Jones' team withdrew at the same time.

“When we all left Condé Nast, I mean, some people were treated very badly,” he says. “And I said, look, get angry. But let's get over it quickly because we had a fantastic time.” Wow, did they do it? Of all the celebrity anecdotes in the book, and there are many (including a meeting with Shirley Maclaine: “you could literally ask her anything; she was never going to read it”), they enter the upper echelons during Jones' life. GQ years, reading less as fact and more as fiction drawn from an F Scott Fitzgerald book, and each name became a more egregious caricature in the contemporary farce we call fame. There are dinners with Paul McCartney, heated disputes with legendary photographer David Bailey (“a grumpy bastard”) and plenty of strange (and anonymous) divas, including the wife of a British actor who insisted on being driven to the GQ Men of the Year Awards. in a bulletproof car, and a “blockbuster singer” who arrived late to the annual event only to tell people backstage, “I'm so sorry, I stink like dick.”

Recurring characters during the GQ The years include Keith Richards, Elton John, Tracey Emin, Damien Hirst and David Bowie. “It was a great celebration of talent,” Jones says of the Men of the Year awards, which attracted such high-caliber names year after year. “The people we were really interested in were the legends.” We agree that, in general, the most famous celebrities are usually the least affected and, therefore, the most likeable. Despite the avid name-dropping, which one review described as “a pathology,” Jones insists that he is friends with “almost no” celebrities. “I think it's a very complicated relationship for some people,” he says, recalling how this became abundantly clear after lunch at a photographer's house. “It was full of photographs of him with famous people. I thought to myself, if you go to all those famous people's houses, he won't appear in any of the photos of him. And I think that's pretty sad.”

Nor is it that Jones is genuflecting at the altar of all the people he mentions; many now disgraced figures appear. There's Harvey Weinstein (“I didn't particularly like him”); Philip Green (“he has done some irregular things”); Russell Brand (“I always thought he was a jerk”). He still gets on well with David Cameron, whom he once spent a year interviewing for a book they worked on together the year before he became prime minister. “I met him at [Chelsea] “I went to the Flower Show and discovered, rather strangely, that he follows me on Instagram. “I think he has made terrible mistakes, but many politicians make them.”

Jones is the former editor of two major men's magazines, one of which used to have a “Girls” section on its website, but he is also the father of two daughters, ages 25 and 23. Did your work affect the way he parented? young woman? “I'm really hoping that everything I did at work didn't affect how I helped raise my daughters,” he jokes. “And my wife raised our daughters. I worked a lot and she bore the brunt, even though she had a full-time job. But I think we educated them pretty well. I naively thought he was going to be a modern father.” Wasn't he? “I mean, I was just a dad,” he laughs. “Although they liked to get free tickets to things. And meet Harry Styles.” He says all this matter-of-factly; Does he regret the most about not being close to his family? “No, because I was close enough. And I was always very good at taking vacations.”

I've been accused of being dismissive, but it's my life, I can be dismissive if I want to be.

Dylan Jones

Within a short time of our interview, it becomes clear that, even though we are here to discuss his memoirs, Jones would prefer to talk about almost anything and anyone other than himself. He is quick to dismiss emotional topics and rejects any questions that scratch beneath the glossy veneer he seems to have spent decades crafting. In the book, Jones writes in visceral detail how his “incredibly violent” RAF veteran father physically abused him and his mother, who was bisexual and would sporadically disappear to be with women he had relationships with. This, Jones reflects, left him to his own devices, “allowing him to [his] father to practice more hours of unsupervised torture” daily to such a degree that it left Jones stuttering.

“It's not to make people feel sorry for me,” he says quickly. “It's just the truth.” Jones has written about her abusive childhood before, most notably in a 2017 article for british gq in which he recalled trying a week-long personal growth course called The Hoffman Process. But the book goes into more detail; Did it spark any conversations with people close to him? “Yes, a lot of people were very surprised,” he says. Has it opened the door to deeper conversations? “No, I don't think so, because I don't particularly want to have them. I'm not that kind of person. And I've been accused of being dismissive, but it's my life, I can be dismissive if I want.”

Jones was a teenager when he was raped; his attacker was someone in his thirties, whom Jones knew vaguely. “My first thought was: This is not right. And it hurts. I was 17 and still a virgin, only now I wasn’t,” he writes.

I'm curious why you haven't talked about it until now. “Because I didn't think my answer was particularly helpful,” she says. “I almost never think about it. I felt quite embarrassed at first, but that lasted for about a week. And I didn't think that was a great example because I know quite a few people who have been raped, I think it happens to a lot of people. And it's traumatizing, and it wasn't for me.”

In the book, Jones describes himself as “indifferent” about it. I ask more about this, noting how, in the aforementioned GQ In his article, he wrote that denial is a manifestation of an abused childhood. Is he really indifferent or is he in denial? “Well, I think both things would be true,” she says, before pausing. “Actually, I don't know the answer to that question. What I do know is that my long-time and long-suffering therapist, whom I see occasionally, once told me, “Look, you shouldn't put things in boxes.” You are meant to accept everything and deal with it. But if you can put things in boxes and that works for you, that's great.'”

It is clearly complicated territory. But despite Jones' discomfort, sharing his story has positively impacted others; Other survivors have been in touch since the book came out. “I've received a couple of anonymous messages,” he adds. “And actually a note from someone I know.” A male rape survivor? “Yeah.” He pauses and, possibly wishing to distance himself from the trauma of others, he returns behind the veneer. “But you know… people… they have to say something. “People have been kind, if you’re going to say something, you probably want to say something pretty encouraging and positive.” He slams the cover of his book on the table in front of us. “Nice color, you know, nice logo color.”

Our time together is almost over; After all, Jones runs a newspaper. Do you see a link between his drive for success and his abusive childhood? “I don't think he wanted a life he didn't have, but he certainly wanted to be successful,” he says. “And there was some momentum there. I tell my daughters this: if you're excited about something, just pursue it. Because that's what you want. That is what will drive you in life. And if you find it at a young age, you're lucky.”