As I ran along the trails through the oak forests of the Palo Alto hills, I was hit with a musky, skunky odor that made my hair stand on end.

I don't know if it was a cougar, but something deep in my brain told me to stop running, move slowly, and keep my wits about me, all the while ruing the day I had become a vegetarian.

Suddenly and surprisingly, I found myself remembering an experiment my father conducted in the 1980s when he tested the idea that animals (i.e., deer) could discriminate between the odors of carnivores and vegetarians.

Susanne Rust, the reporter, and her father, Langbourne Rust, in a pony cart in 1979.

(Courtesy of Susanne Rust)

Forty years later, I was taking my father's question in a new, situation-specific direction: Can a mountain lion, by scent, detect a vegetarian? And although mountain lions occasionally consume carnivores and omnivores, did it smell more like easy prey (i.e. breakfast) than a fellow predator?

My race ended walking and without an ambush. But the question stuck and made me think about my father and led me to spend weeks reading articles and research studies and talking to scientists and experts on predation and odors.

I would learn that there is one animal in particular that can discriminate between the smells of humans who eat meat and those who don't, and it is neither the mountain lion nor the deer.

I grew up in a small, woodsy but upscale town in the Hudson River Valley, 30 miles north of Manhattan during the 1970s and '80s. And from the time I was 10, I knew that my father was considered, well… different. .

There were skins of small mammals and birds hanging in our garage that my father used to make fishing flies. And although most of my friends' parents traveled into the city, my father's office was in our house, which meant he was the father waiting at the bus stop.

But it was the venison we ate year-round that really meant to me that something was different in the Rust house.

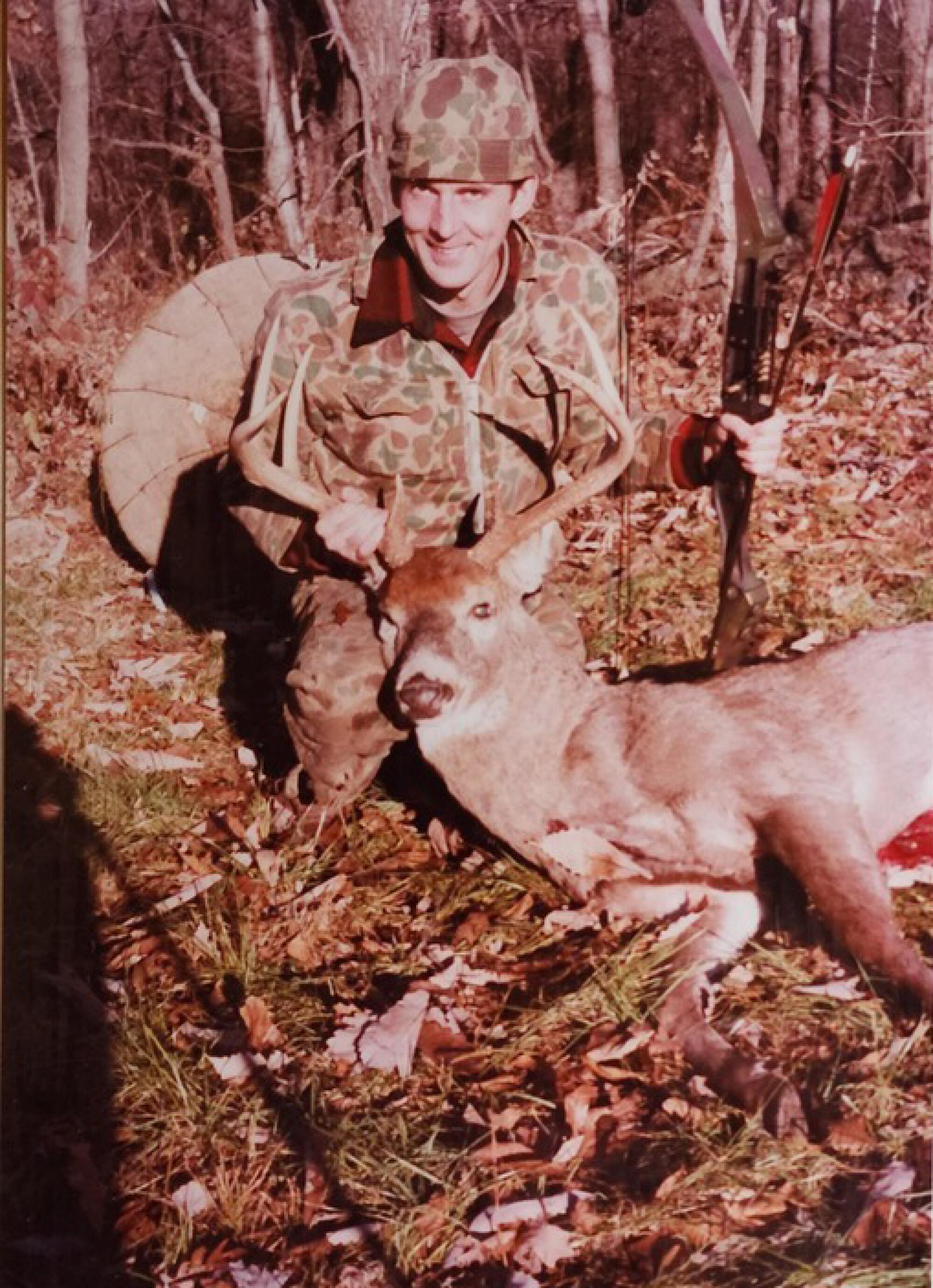

In the evenings and on weekends, while other fathers played golf or tennis, my father would put on a one-piece, zippered camouflage suit. He would paint his face in brown, black, and olive stripes and sneak into the woods behind our house, compound bow under his arm, to hunt deer.

Starting in the late 1970s, Langbourne Rust would stop eating meat for the two months before deer hunting season. He believed that by smelling like someone who doesn't eat meat, he would be less likely to scare his prey.

(Courtesy of Susanne Rust)

He was so well camouflaged that when he went three or four feet into the woods, it was impossible to see him.

This was a problem for my brother and me, because we were only allowed to watch television for one hour a day. When my father went hunting, we would surreptitiously turn on the set, trying to watch reruns of “I Love Lucy” and “The Carol Burnett Show,” not knowing if he was standing at the edge of the woods watching us. Turns out he occasionally was.

My father, trained as a psychologist, had built a career in children's marketing, which occasionally required a trip to the city. It was on one of these expeditions that my father met a friend who told him about a weapons system he had worked on during the Vietnam War called Project Batboy.

According to my father's recollection of the conversation, the system consisted of mechanical chemo-detection devices designed to distinguish, in the field, between carnivorous American troops and the mostly vegetarian North Vietnamese.

I haven't been able to verify Project Batboy, but I learned that the United States built a chemotherapy detection device called a “people tracker.”

South Vietnamese Army Rangers, supported by helicopters, make their way through tall grass during an assault.

(Tim Page/Corbis via Getty Images)

Deployed in low-flying helicopters, it collected air samples and, through a chemical reaction to ammonia, an indicator of urine or sweat, signaled the presence of humans. The tracker was also able to detect smoke, a sign of human activity. Once detected, the site was marked on a map and bombed that day or the next morning. (Walter Cronkite once hosted a segment on the tracker. You can watch it here.)

Apparently, it didn't take long before the North Vietnamese realized what was happening and began hanging buckets of urine from trees to throw off the Americans.

According to a friend of my father's, the Batboys took the people tracker concept a step further, resulting in a device that could somehow discriminate between carnivores and vegetarians (which, like the people tracker, occasionally selected animals unprepared).

My dad said he didn't think much about the anecdote at the time, other than considering the horror of it all. But a few months later, as hunting season approached, an idea emerged.

For years he not only used camouflage clothing, but also artificial scents, which he said didn't really seem to work, but which hunters often use to attract or confuse their prey.

In an article for Sports Afield magazine in 1984, my father wrote, “The challenge of hunting… is the challenge of overcoming the deer's sense of smell.” He only came to two firm conclusions about artificial scents: he wrote: “1) If I smell like deer, dogs will chase me, and 2) if I smell like skunk, people will stay away from me.” (The same issue included an article titled “Sex and the Single Hunter,” but that's another story.)

He had noticed that the deer seemed to get scared if he was against them. Was it because they could tell he was a predator by the carnivorous smell of him?

Thus began an experiment in which my father became a vegetarian in the two months before hunting season, a tactic he said was highly successful, but which came to an end in 2007 after contracting Lyme disease. , a tick-borne disease that seems For the sixth time, it will focus on people who spend a lot of time in the forest.

His hunting days were over.

Smell is the oldest animal sense, said Catherine Price, a behavioral ecologist at the University of Sydney in Australia.

“Bacteria use it and basically all organisms use it,” he said.

They can use it to find food, avoid predation, and, in the case of animals that have sex to reproduce, find a mate. In the case of deer, they use it for all three purposes. But did my father, by avoiding meat, fool the deer into thinking it was harmless? That's not so clear.

“A lot of these hunting theories I call anecdotal,” said Carter Niemeyer, a retired federal and professional wildlife trapper who has used scents to attract animals for more than six decades. “His personal data on him told him it was working for him,” he said of my father, “so I wouldn't discredit him, even if I might be skeptical.”

As for my question of whether a cougar could tell if I was a vegetarian and then use that as information to decide whether to attack, Niemeyer found it unlikely.

First of all: Mountain lions are visual predators, he said. My race, more than my smell, would have made me a target. Which isn't to say mountain lions don't use their sense of smell to find prey, she said. They probably do.

“It's similar with bear attacks,” he said. “Like a grizzly bear attacking a hunter who is gutting a moose. “All of a sudden they get that overwhelming smell of moose blood and they come to take a look…there's that aspect of predators needing to identify what they're attacking.”

That's why when you're in the woods, especially in bear and mountain lion country, you want to make sure you announce yourself with a “Hey, bear! Hey bear!

“Speak out loud, identify yourself and allow those predators to take in the whole scene and all the humanity and help them realize that this is not one of my usual prey,” he said.

Humans probably smell, well, human to most wildlife: without fur and with our sweat glands oozing on the surface, we're a pretty stinky creature, or at least incredibly recognizable. The relatively small differences between us—our soap choices, laundry detergent preferences, and diets—probably aren't very important or relevant.

Those extra smells are just noise sputtering around the only important signal, Price said, which is that we are human and therefore signals that it is time for that animal to run or hide.

That is, unless that animal evolved to feed specifically on us.

Some species of mosquitoes, for example, feed only on human blood. They don't like deer, dogs or cows. Just people. Apparently they are attracted to the smell.

Niels Verhulst, a researcher at the Institute of Parasitology at the University of Zurich, said that it is the composition and composition of the bacterial species that we harbor on our skin that gives us our smell. Part of that is determined by genetics, part by the products we use on our skin, and part by our diet.

“But how important are these different parts? That’s something we don’t know yet,” she said, noting that there is a positive correlation between drinking beer and attractiveness to mosquitoes.

But what is clear is that science has found only one species that can discriminate between vegetarian and carnivorous humans: Homo sapiens.

In 2006, Jan Havlicek, director of the Human Ethology program at Charles University in Prague, set up an experiment involving young college-aged women (who were not taking hormonal contraceptives, which could theoretically affect the perception of the smell of a woman). to smell a series of odor-impregnated strips of cloth that had been worn in the armpits of men of similar age.

The women were asked to rate the “pleasantness, attractiveness, masculinity, and intensity” of the sweat-infused samples. It turns out, Havlicek said, that they found the smells of vegetarians “more attractive, more pleasant and less intense” than those of carnivores.

Thirteen years later, a team of Australian researchers repeated a similar study and came to slightly contradictory conclusions: the most pleasant aromas came from men who ate a lot of fruits and vegetables. But it wasn't the men who ate meat who got the lowest scores. That classification was for the kids who ate a lot of carbs.

(Interesting side note: Those results reflect data showing that men who have yellower skin richer in carotenoids, a byproduct of eating lots of fruits and vegetables, are also more attractive to women.)

As for my dad? He never returned to his vegetarian days, although he eats much less meat than before. Which may explain the constant presence of deer eating flowers and bushes in my parents' garden.