TO A few weeks ago, a friend told me that he sometimes thought about quitting his job. I told him that sometimes I also thought about leaving my job. So together we bonded over our mutual hatred of workplace drudgery, the everyday miseries of leaving home, and our shared dreams of self-inflicted unemployment. Then we recognized that we both actually liked our jobs. So we changed the subject.

Feeling apathetic about work and going back and forth between accepting it wholeheartedly and telling it that it's terrible and that you want it to die is a modern constant. Everyone seems to be on it: whether you work in a shop, an office, or freelance from home, there's nothing more appealing than shutting down and staring at the ceiling instead of doing what you're paid to do. Or at least take some time to fantasize about having a completely different life and calling. And some workers are supposedly doing just that: dropping tools, metaphorical or not, and deceiving their employers entirely.

According to new claims from a prominent employment lawyer, this is more common among specific demographic groups. “What we've noticed is that, in those sectors where perhaps wages and skills are a little bit lower, there is a definite increase in the number of employees who simply don't show up to work,” said Nick Hurley of Charles Russell Speechlys. The Daily Telegraph this week. He identified retail and hospitality as the hardest hit sectors, young people as the biggest culprits and mental health conditions and long-term post-Covid illnesses as some of the key factors leading to employees going AWOL. .

Some of this has to be taken with a pinch of salt. Stories like these often feel a bit like rage bingo: combine some worrying employment figures alongside images of proper and/or lazy young adults self-diagnosing themselves as depressed or anxious, and you can practically hear readers clicking away in indignation. through his sweats of anger. . That said, if the picture the statistics paint is truly accurate, can young workers really be blamed for falling off the map?

In January, the charity Mental Health UK warned that Britain risks becoming a “burnt out nation”. The kind of phrasing that was once synonymous with gloomy epigraphs at the beginning of dystopian fiction is now just something we say to each other. “We live in unprecedented times,” explained CEO Brian Dow. “Life outside of work has become increasingly difficult due to the cost of living crisis and pressures on public services, while global challenges such as climate change and artificial intelligence fuel stress, anxiety and feelings of hopelessness.”

On a related note, a YouGov survey of 2,060 adults found that 35 percent of participants had experienced high or extreme levels of pressure at work. Twenty percent of them had taken time off due to mental health issues in the previous year. Is perhaps apathy simply a natural consequence of feeling increasingly overwhelmed and exhausted?

Apathy towards work is not limited to a certain generation. It's just the latest stick with which to beat Generations Y and Z.

David Rice, People Management

David Rice, human resources expert at People Management People, tells me that apathy in the workplace isn't necessarily something to worry about. “No one can be connected all the time,” he says. “There will be times when your enthusiasm and energy will wane. That's perfectly natural. It can be negative if you have performance-based incentives that you fail to achieve because you don't find the strength to move forward. But at the same time, it can create a little distance between you and work. It can give you some clarity about what really matters, allow you to work on other things, and let go of what you can't control. Ultimately, those are good things.”

He is also unsure of the idea that workplace apathy is the exclusive domain of young people. “It's not limited to a certain generation,” he says. “It's just the latest stick with which to beat Generations Y and Z.” Anecdotally, I don't remember being around anyone in my life, from co-workers to grandparents, who hasn't once or twice confessed to wanting to leave their job in a blaze of glory, or admitted to wasting time at their workplace killing time. time until you can flee to the nearest exit. The act of working is occasionally – or often, for some – a stale bore. It was true in 1978, it is true in 2023 and it will still be true in 2050, when we will be shaking the dust off our robot overlords in exchange for pieces of bread.

However, if age plays an important role here, it is in young people's relationship with justice. Keeping calm and carrying on (aka nihilistically walking through abject misery out of a sense of moral duty) is an exhausting cornerstone of the British psyche. But it has become less attractive in recent decades. Wages have stagnated, industries have collapsed, and the basic tenets of adult stability – from raising a family to owning a home to the looming threat of ever-later or non-existent retirement – are in the process of becoming completely unattainable for many young people. people, especially those who live in big cities. Without that warm embrace of stability (coming, for example, from a stable labor market or a non-zero-hours contract), where is the incentive to stay? Go out. Get drunk. Get a tattoo on your face. Choose life.

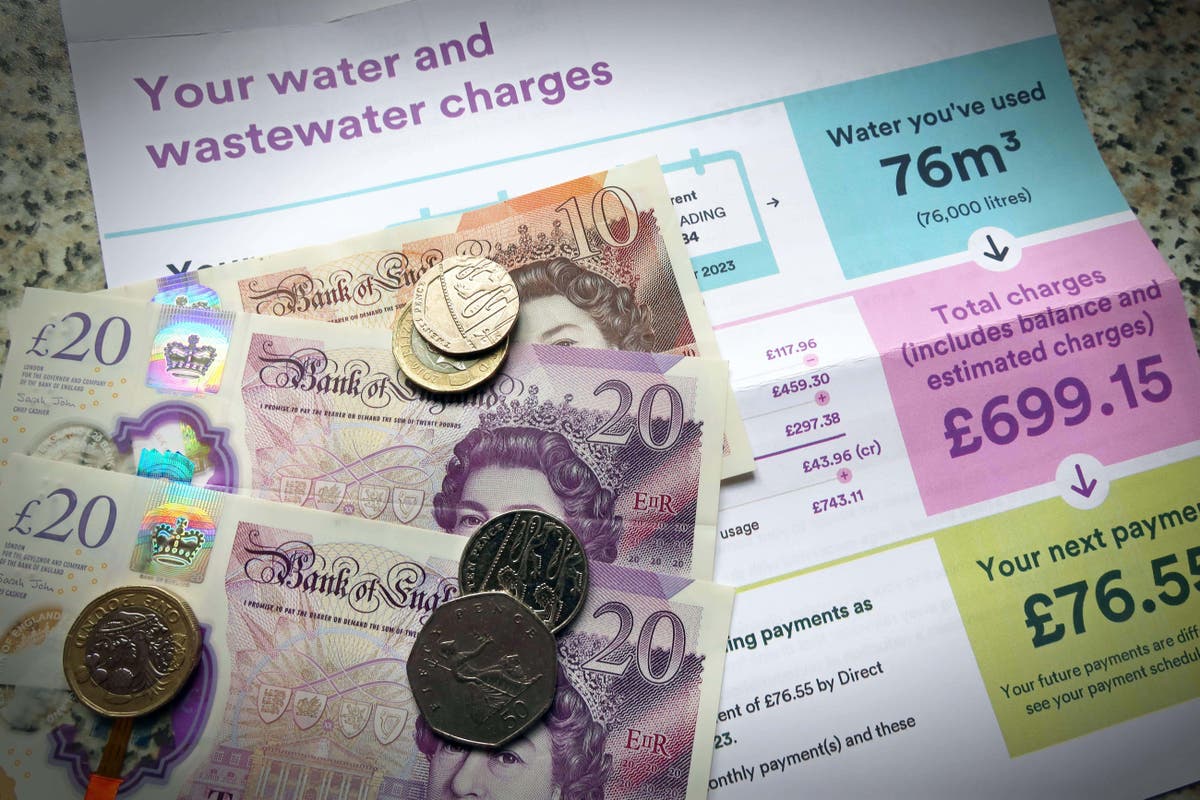

A long day at the office: there are few things more attractive than closing instead of doing what you're paid to do

(iStock)

This is at the more drastic end of possible answers. But it speaks to a general sense of the sands shifting when it comes to work and our relationship with it. Discussion of a rise in apathetic employees coincides with new gentle mockery of the four-day work week, which just a few days ago was described as “inevitable” by one advocate of the policy; Pilot tests carried out so far have seen a range of benefits, from increased productivity to improved worker well-being. Flexible working is already widespread in certain industries.

It seems like a reboot of sorts is coming; The question is how long it will take. Meanwhile, sometimes it's healthier to become desensitized to your work for periods of time rather than suffer a mortifying meltdown at your desk. “You need to determine whether the apathy that occurs is related to exhaustion or simply the need to invest time and energy in other things,” says Rice. “Make sure you get enough rest and allow yourself the freedom to think about other paths you can take in your life. It's okay, and even necessary, to entertain yourself with these things from time to time.

He adds that it also works both ways: It can't simply be the employee's responsibility to ask for help when they need it or to find their own joy in the workplace. If you're a manager, she says, “find projects that people are passionate about and give them the space to work on them. Try to eliminate excessive obstacles or bureaucracy in your workflows. Encourage them to take advantage of their vacation time, too. “Sometimes they just need to get out of a routine or see and do something exciting.”

In other words, feelings of apathy are not worth panicking about. Have a moan to a friend. Leave it in your head. Scroll through your phone while that important email remains unanswered for a few more hours. All of this could even be a blessing in the long run.