International criticism of the fast fashion industry for its waste, labor abuses and carbon emissions has failed to slow it, but new legislation could disrupt the flood of products, such as floral-print sweaters selling for $2.99, children's T-shirts for $4.26 or tank tops for $4.88.

The term “fast fashion” — which emerged in the 1990s alongside Zara, a European company that sold runway-inspired styles at affordable prices — has come to define trendy, low-cost, throwaway clothing.

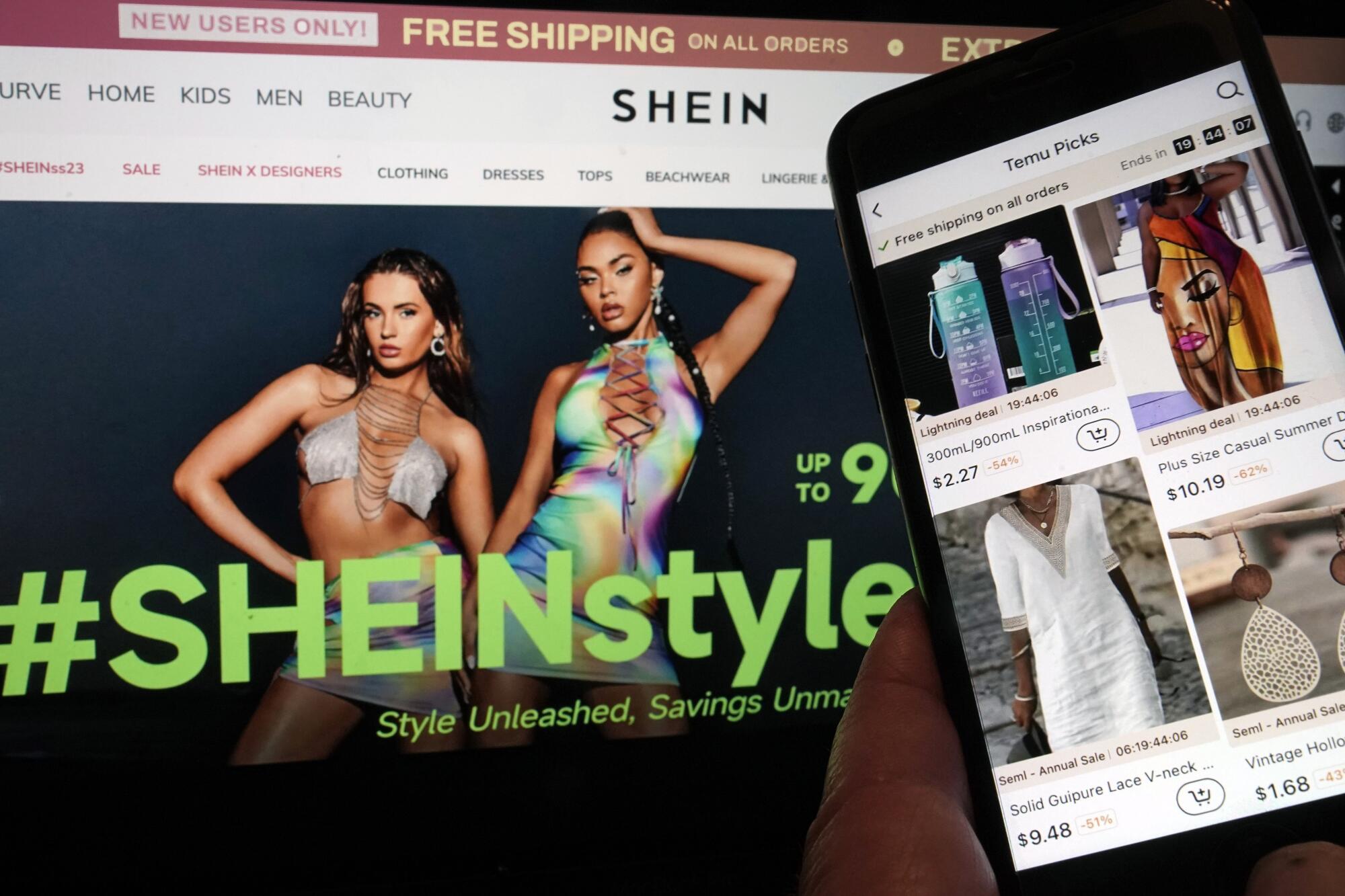

This business model has been popular with shoppers and brands, who keep inventories low, try to predict what customers want and use highly flexible supply chains to achieve rapid response. Recent versions are exemplified by successful Chinese e-commerce platforms Shein and Temu.

A traditional retailer might offer 1,000 different styles a year, said Sheng Lu, a professor and graduate director of fashion and apparel studies at the University of Delaware. Contrast that with the first generation of fast-fashion brands, Zara and H&M, which launched about 20,000 a year. Shein, he added, which has earned the label “ultra-fast fashion,” produces 1.5 million different styles a year.

According to a consultancy, clothing production doubled between 2000 and 2014, and the number of items purchased per capita increased by 60%.

(Thibault Camus / Associated Press)

According to consultancy McKinsey & Co., which estimates the global fashion industry is worth $1.7 trillion, clothing production doubled between 2000 and 2014, and the number of items purchased per capita increased by 60%. At current rates, McKinsey predicts that clothing and footwear consumption will rise from 62 million tons in 2019 to 102 million tons in 2030, “the equivalent of more than 500 billion additional T-shirts,” according to the Clean Clothes Campaign.

As clothing prices have plummeted (just a few months ago, McKinsey reported that the average price of an item at Shein is $14, $26 at H&M, and $34 at Zara), customers have become less hesitant to throw them away. Less than 1% of fashion textiles are recycled, McKinsey reported, and 3 in 5 garments end up in a landfill or are incinerated each year.

But as fast fashion grows in popularity, so does the backlash against it, drawing the ire of environmental groups, labor activists and lawmakers across Europe and the United States. “The debate over fast fashion is quickly moving from the traditional commercial aspect to the political aspect,” Lu said.

Recent laws have been passed in several countries to curb the environmental impact of the fashion industry, whose greenhouse gas emissions, which contribute to global warming, are estimated to exceed those of international flights and shipping combined. McKinsey estimates that the fashion industry accounts for between 3% and 8% of the world's greenhouse gas emissions, and could increase by another 30% by 2030.

Dame Sall sorts and folds second-hand jeans imported from Italy in a warehouse in Dakar, Senegal. Second-hand T-shirts, jeans and dresses are piled high along the busy streets of Dakar's Colobane district, where people buy them at a fraction of their original price.

(Jane Hahn/Associated Press)

France is leading the fight against fast fashion. In March, the lower house of parliament approved a bill that would ban advertising for such items and impose fines for each item sold. France has also proposed a European Union-wide ban on used clothing exports to discourage the discarding of cheap products that end up in landfills abroad.

New York lawmakers have drafted a bill that would require major fashion brands doing business in the state to map and disclose supply chains to prevent labor exploitation and environmental damage.

According to McKinsey’s State of Fashion 2024 report, 87% of fashion executives surveyed believe sustainability regulations will impact their businesses this year. “The rules of the game are changing,” Lu said. “These regulations and changing consumer behavior will really put some pressure on these fast fashion brands.”

Shein, which uses predictive analytics to determine which clothing designs will sell best, has argued its business model is less wasteful than traditional retailers because it produces only what customers order.

Still, the companies most associated with the phenomenon are trying to diversify their offerings to avoid the fast fashion label and all its negative connotations.

With a new third-party marketplace, Shein customers can now find secondhand luxury items on its site. Zara, the former fast-fashion pioneer, has pledged to transition to sustainable, organic or recycled materials by 2025 and incorporate higher-quality, higher-cost offerings into its product lines.

But the influence of fast fashion has not disappeared, as evidenced by the global apparel supply chain, which has been disrupted as traditional retailers have adopted practices to increase their own speed and flexibility.

Before the advent of fast fashion, a standard garment took about two months to manufacture, according to Raymond Wong, a professor in the department of logistics and maritime studies at the Hong Kong Polytechnic University. Now, fast fashion can produce an item, from concept to delivery, in less than two weeks.

And as production capacities have accelerated, so have the life cycles of the garments retailers sell. While clothing collections have traditionally been seasonal, fast fashion brands can now release at least one new collection per month, Wong said.

Fast fashion retailers Shein and Temu have proven wildly popular in the United States.

(Richard Drew/Associated Press)

And brands have learned that being fast has its rewards.

Profit margins for companies that embrace fast fashion are generally higher than those of traditional retailers, Wong said, because they prioritize sales volume and low-cost production. Keeping inventory lean also means they don't have to offer deep discounts to get rid of unsold merchandise.

“This is the philosophy of fast fashion retail: if you can get your item in the store a day earlier, you have a greater chance and probability of selling more,” Wong said.

A more flexible production cycle means brands are working with more vendors, manufacturers and suppliers than before, making it more difficult to assess the supply chain for violations of labor and environmental standards.

Sanchita Saxena, a professor at the University of California, Berkeley who studies labor and apparel supply chains in Asia, said that while more brands are trying to improve sustainability, their cost expectations are making it difficult for suppliers, many of whom are suffering losses on accepted orders, to take action.

The impact of fast fashion is “terrible for workers because the cycle is so fast and the turnaround time is so fast that there is no way a human being can produce the quantity of goods that are required,” Saxena said. “But they are under incredible pressure to do so and they are always under pressure on price.”

Despite concerns about the negative impacts of fast fashion and sustainability commitments, experts say consumers alone will not have much influence on how the clothing supply chain adapts.

Garment industry employees work at Arrival Fashion Limited in Bangladesh. Critics of fast fashion have long warned consumers to stop treating clothes as disposable items.

(Mahmud Hossain Opu / Associated Press)

“Consumers are making it clear they want to shop more ethically and responsibly, but they’re not doing it at the scale that’s necessary for brands to take action,” said Divya Demato, chief executive of GoodOps, a San Francisco-based supply chain consultancy.

Temu, a low-cost shopping app that gained popularity last year, was created by Chinese e-commerce platform Pinduoduo to tap into that price sensitivity among American consumers.

According to McKinsey, 40% of American consumers have purchased from Shein or Temu in the past 12 months. Many of those surveyed said they intend to buy more from those fast fashion brands in the next two to three years.

“It becomes a bit of a chicken-and-egg situation. Brands say, ‘Consumers want it, so we’re giving it to them,’ and consumers say, ‘Well, brands are doing this, so we’re buying it,’” Saxena said. “Which came first? I don’t know, but someone has to stop that cycle.”

Special correspondent Huiyee Chiew in Taipei, Taiwan, contributed to this report.