Since the aviar flu came in the force in the California dairy industry in 2024, it has not only made cows ill, but has killed hundreds of domestic cats. Some cats of pets living in dairy farms were infected with the H5N1 virus drinking raw milk. Both pets and wild barn cats became ill after eating raw pet foods that housed the virus. Others achieved it by eating infected wild birds, rats or mice, or by contact with clothing or contaminated boots of dairy workers.

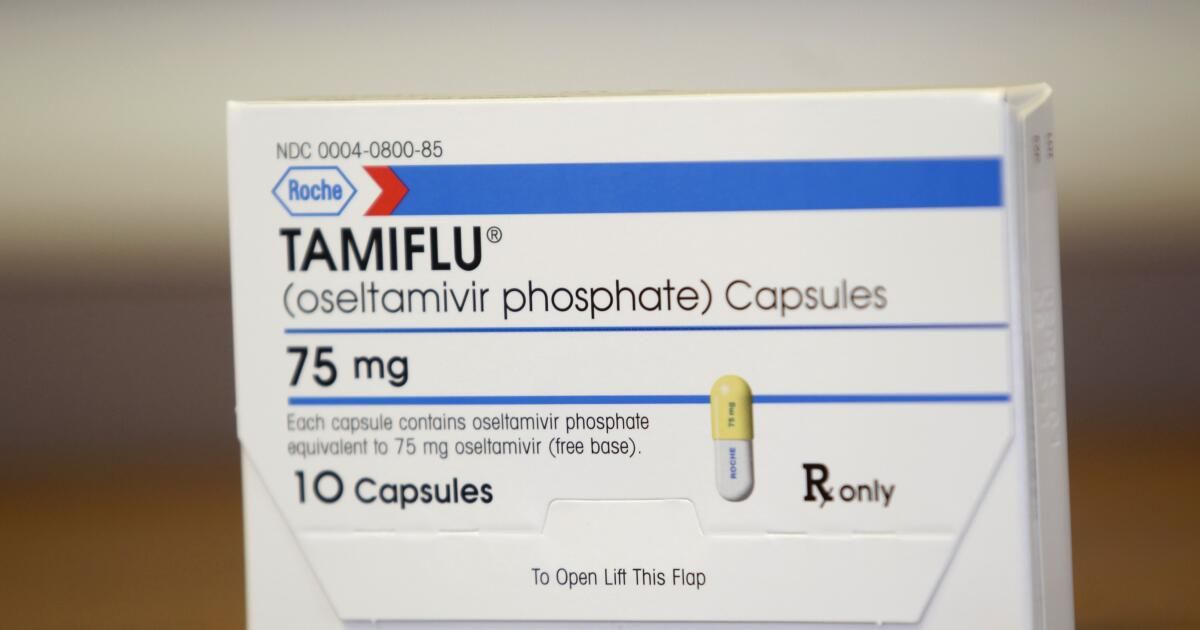

But a new published case suggests that death can be avoided if infected cats are treated early with antiviral medications, such as tamiflu or oseltamivir. Once treated, these animals can take antibodies to the virus that makes them resistant to reinfection, at least temporarily.

The discovery was made by Jake Gómez, a veterinarian who treats small animals, such as cats and dogs, as well as large, including dairy cows, his clinic, veterinary hospital of small animals of Cross Street, in Tulare.

The past fall, Gomez worked with a team of scientists from the University of Maryland and the University of Texas that were in the central valley collecting blood samples of outdoor cats in Dairy Pharms, seeking to see if they could find antibodies against the H5N1 flu.

Cats are exquisitely sensitive to H5N1; One of the revealing signs that a dairy flock is infected is the presence of dead barn cats.

On October 31, the owner of a cat brought an inner/exterior cat to the Gomez clinic that was ADR, an acronym for technical veterinarian that represents “is not doing the right thing.”

The cat was updated in all its vaccines and the owner did not report a known exhibition to toxic chemicals.

Gomez offered to do blood and urine analysis to investigate what was happening more deeply, but the owner refused. Then, Gomez sent them home with an antibiotic and an appetite stimulant. Two days later, the cat died.

It turned out that the family had had another cat to die just a few days before, Gomez said, remembering the visit.

Also during that time, Gomez treated the herds of infected dairy around Tulare. Thousands of cows became ill from the virus. He learned that the family with sick cats lived less than one mile of an infected dairy, and the owner of cats worked by handing hay to local dairy, spending time in infected farms.

“Taking into account how fast it moved from one cat to another, it occurred to me that it could be H5N1,” he said.

Gómez said he communicated with the United States Department of Agriculture and the Food and Agriculture Department of California to see if they would try dead animals for the virus. The agencies, he said, gave him the fugitive and could not make anyone respond to his calls, which said he was disconcerting, considering the rapid answer when he alerted them about infected cattle.

“If I called to tell you that a pack of dairy had, within 24 hours a SWAT team of the USDA and the state would be investing the farm,” he said. But for a cat? Irons.

On November 6 and 7, the family returned with two most sick cats.

Gomez said he still didn't know what they had, but that he had the suspicion that they could infect H5N1. Then, he treated them with the antiviral oseltamivir, also known as Tamiflu, and recovered.

In March of this year, the blood samples collected from the two cats showed high levels of antibodies against H5N1, which suggests that cats had been exposed.

The case was published in One Health magazine.

Kristen Coleman, an infectious disease researcher in the air in the Public Health Faculty of the University of Maryland, and author in the document, said that the findings suggest that cats can be treated effectively and that antiviral medications could help prevent greater propagation of the virus among cats that live in the same house and humans that care for them.

She said that there have been no known transmissions from cats to humans in this outbreak, but in the past: in 2005, Thai tigators were infected by tigers who had the virus, and in 2016, New York veterinarians in a refuge of animals made him care for sick cats.

But Jane Sykes, a professor of Medicine and Epidemiology at the School of Veterinary Medicine of UC Davis, said she has not convinced cats in this case she actually had H5N1, and urged people to read the study with care and caution.

“It is possible that the positive results of the antibody test are not related to the reasons why these two cats died,” he said. “The virus was not detected in any of the four cats, so the infection was not tested.”

And if the cats recovered because they were treated with Tamiflu, or if the medicine was incidental and had recovered on their own, from another virus, infection or ailment, it is not clear.

In addition, he said, nobody has investigated the effects of Tamiflu on cats. And although these two cats seemed to tolerate the drug, that does not mean that other cats will.

“Cats metabolize some of the anti -infection compounds very differently from other animals, including people, and are quite susceptible to the bad side effects of many of these drugs,” he said. “We have to be very careful when we start only using random antiviral medications that have not been studied for cat safety, because they are very likely to have bad side effects.”

That said, he said that if he faced a similar situation, a high certainty that a cat had been exposed, either by drinking raw milk or eating raw foods that had been infected, he would consider prescribing the medication. But she would warn her client that she was experimental, and the animal could die of the drug.

She said there are numerous laboratories throughout the country that will test blood and urine for the virus.

Sykes urged people not to feed raw food or milk to their pets.

She said that she is seeing more raw food products for pets “and people want them, and do not understand the damage and the fact that some of these are contaminated for a long period of time with influenza viruses, such as H5N1.”

Neither freezing nor smoking kill the virus.

“It's surprising how big this industry is getting,” Sykes said. “It's crazy.”