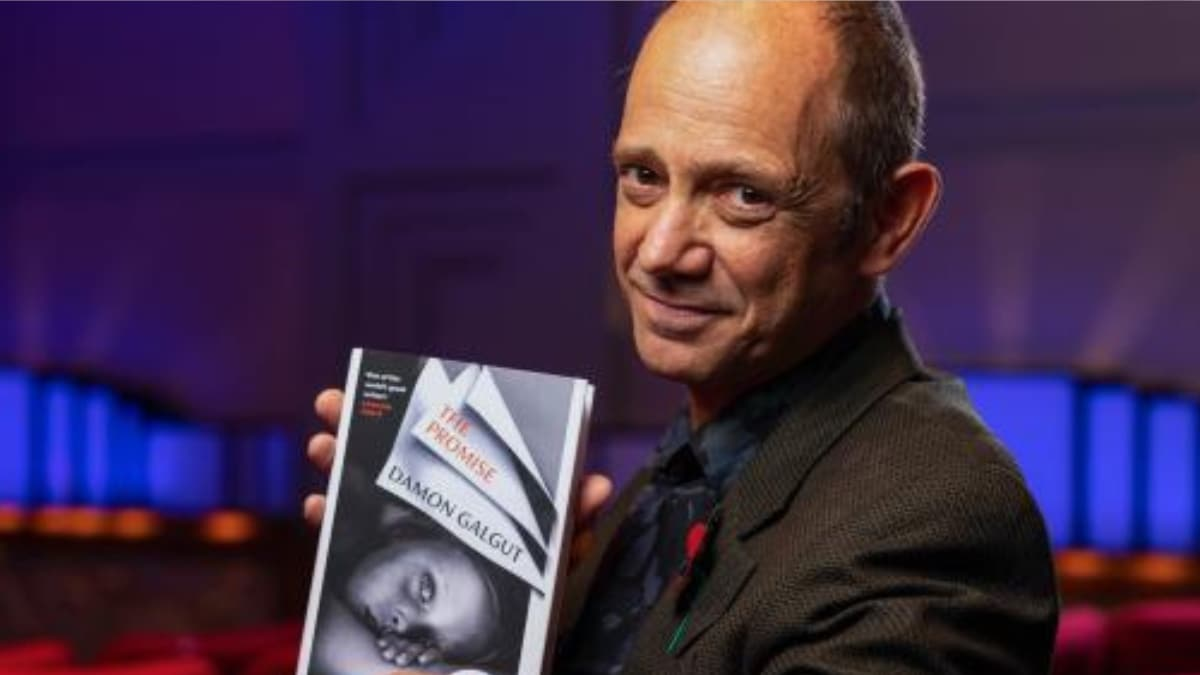

Damon Galgut's impact on modern literature is something that should often be discussed and appreciated. His win at the 2021 Booker International Prize was very well received and was definitely celebrated everywhere. There are very few writers who address topics such as racism and injustice as precisely and intricately as he does. He is all set to speak at the 17th Jaipur Literature Festival for the first time since he won the Booker Prize. Fans and admirers of his work from all walks of life are very interested in listening to him in the well-curated sessions.

The brilliant author, ahead of his JLF sessions, sat down with News18 for an exclusive conversation where he spoke about his childhood, his career, his Booker nominations and finally winning it after years and much more.

Excerpts from the interview-

Can you share a little about your early experiences and what led you to become a writer?

I was very sick as a child and spent a lot of time in hospitals and sick beds, while various visitors read to me. My love for books began during that period. It was intense enough to make me need to create them myself. I started very young (and very bad) but I've been at it ever since and I've learned a few things along the way.

Who are some of the writers or literary figures who have most influenced your work?

William Faulkner. Samuel Beckett. Virginia Woolf.

His novels often explore the landscape and people of South Africa. How do the geography and environment of a place inspire or influence your storytelling?

It is very important that in that scenario there is a presence in the narrative, as significant as any character. I can't start writing anything without a strong sense of place. By this I mean its atmosphere, texture and mood, not necessarily the story of it.

“The Good Doctor” and “In a Strange Room” received critical acclaim. Can you talk about the themes and inspirations behind these works?

They are very different books. The first arose from the optimistic period immediately after our first democratic elections, when we still naively believed that we could remake our country with an inspiring new image. Something in me was cynical and incredulous about that project, and I gave voice to the clash between idealism and realism in that novel. In A Strange Room, on the other hand, is about travel, memory and time, and has nothing to do with South Africa. To be honest, that was part of the appeal of writing it: that I could escape the story for a while. But I could only achieve this by moving away from my country and stripping myself of any strong sign of identity.

How did it feel to be shortlisted twice for the Booker Prize before finally winning it, and how do you think that recognition has impacted your career?

Being a writer means being ignored and overlooked. So, being noticed in a meaningful way is, of course, a thrill and a blessing. I was happy to be on the short list; It attracted some esteem and critical attention, but not much. Winning the award was something like being at the epicenter of a massive explosion. It would be foolish to deny that everything in my life has changed, both for the better and the worse. In short, it would be true to say that I'm glad it happened, but I'm also glad it's behind us.

Do you think people or readers perceive you differently now that you're a Booker Prize-winning author?

I don't know. What do you think?

Returning to your novels, your writings often delve into questions of identity. How do you approach the exploration of identity in your writing?

I don't think about it that way. I just know that the question of identity intrigues me. If I sat next to you on a plane and we started a conversation, you would believe almost everything I told you about myself. My job, my past, my circumstances. Without external reference points, there is nothing to contradict my story. So in a way, our identities are flimsy and arbitrary, things we put on and take off like a hat. On the other hand, we feel deeply connected to the land and to other people through a deep history, and that is also identity. Then it is everything and nothing, heavy and light as air. A mystery, in many ways.

Your characters are often complex and layered. How do you develop your characters? Are they based on real-life experiences or people?

They are aspects of other people, mixed with aspects of me. Characters often only become believable when they behave against their own nature: the selfish person does something generous, and the kind person is momentarily cruel. Human nature is contradictory.

How do you perceive the current state of South African literature and how has it evolved over the years?

I am not an academic and I am not well read in South African literature. But I am aware that it has a rich tradition, with talents that far exceed the small audience. I suppose it's true that literature has primarily served some purpose here, whether to give a civilized voice to the colonial project or as a form of resistance to white domination. But we are in an age where the purpose of novels is unclear. What exactly are we resisting? What are we giving voice to? The answers are not obvious.

What advice would you give to aspiring writers trying to find their voice and navigate the world of literature?

Stop, stop, before it's too late.

You will be speaking at JLF in February 2024, what could fans and audiences expect from your session?

I have no idea. Synchronized swimming and interpretive dance are unlikely. I can answer some questions. I'll try to be interesting.

Can you share any ideas about your current or future projects?

Busy working on some short stories. Which I need to get back to right now! Thanks for the chat…