The third of Baroo’s six dishes – the dish that fully embodies the impulse behind Kwang Uh’s light, confident modern Korean cuisine – is a fried sole ssam, prepared on a buttery lettuce leaf that lives up to its name.

Its gentle folds cradle the fish, which is wrapped in a batter made with three flours and vodka for maximum crunchiness, and latticed with seaweed powder to give it the appearance of tiny green veins. Red shiso and perilla add their distinctive peppery kick, resembling that of mint. Sauces of gooseberry emulsion and seaweed remoulade go in separate directions, astringent and rich, creating sharp contrasts.

Each element brings an organic beauty that invites you to grab it, which is exactly the intention. In the hand, the packaging disappears in four or five bites. In the memory, the layered intrigues will continue to haunt.

Baroo's Tae, a dish of dan hobak, ssanghwacha cappuccino, seed puff pastry and red yeast makgeolli with ndnja, gouda and red currants. (Silvia Razgova / For The Times)

Diners enjoy dinner service at Baroo. (Silvia Razgova/For The Times)

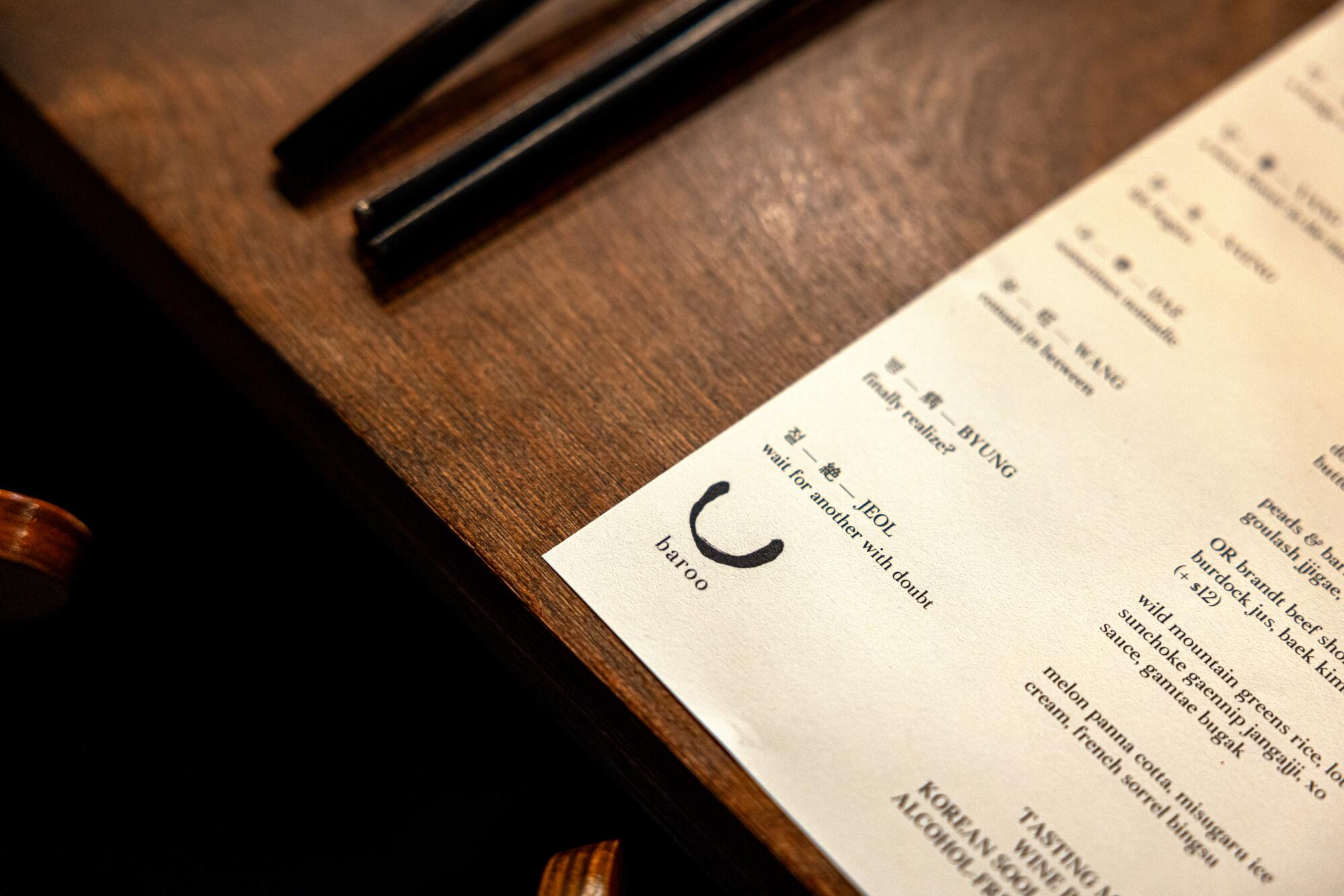

Baroo's elegant tasting menu.

(Silvia Razgova / For The Times)

The entire experience of dining in Baroo's elegant and comfortable Arts District dining room can be like this.

At first glance, this is a beautiful tasting menu, priced at $110 per person and paced nicely to appease Angelenos otherwise impatient with prix-fixe dinners. The emphasis is on vegetables, herbs, and seafood; one dish consists of densely delicious short ribs or pork neck alongside a singular bowl of rice seasoned with things like dried shepherd’s purse (a plant in the mustard family) and XO sauce made from chorizo. Uh is a master of fermentation. Kimchi, pickles, the Korean building blocks of soy-based jangs, and even buttermilk, combined in a lemongrass-infused sauce, open the door to worlds of flavor never before seen. In Los Angeles, where traditional expressions of cuisine define the ethos of Korean restaurants, Baroo stands out as the city’s most persuasive foray into innovation.

There's also a lot more powerful context if you look for it.

Baroo, with its many longtime fans (I'm among them), began as a project nearly a decade ago in an unassuming Hollywood strip mall. Initially partnering with childhood friend Matthew Kim, Uh poured years of culinary education and stints in kitchens around the world into intricate, supremely satisfying cereal and pasta bowls that sold for $9 to $15 each.

Chef Kwang Uh, right, and Mina Park, owners of Baroo.

(Silvia Razgova / For The Times)

Running the restaurant as a couple was a grueling task to the point that it wasn’t sustainable. In 2017, after the restaurant received waves of local and national praise, Uh left the restaurant for more than six months to live at Baekyangsa Temple in South Korea. She was there to do an apprenticeship with Jeong Kwan, the Zen Buddhist nun and chef who received global attention that same year for appearing on an episode of “Chef’s Table” on Netflix. While there, Uh also met chef and writer Mina Park. They eventually married and became business partners, charting the future of Baroo after its first iteration closed for good in the fall of 2018.

Even before its Arts District reincarnation came to light last September, Baroo was still very much in the L.A. restaurant consciousness. Yes, the model was unsustainable, but the incredibly detailed grain bowls and oxtail ragu noodles with gochujang sauce were like nothing seen before or since: mind-blowing, comforting, and stubbornly affordable. Above all, the cooking was personal and graceful. Uh found her way to something new on those plates by connecting with her identity, with all of it, with her background, her travels, her curiosity, her intellect, her imagination.

Creating menus that draw on a chef’s narrative is endemic in Los Angeles, from street taco stands to omakase counters. But the synthesis of ideas in Baroo’s kitchen was empowering in a new way. Even if none of our next generation of talent ate at Uh’s original restaurant, I see a line of self-determination running through recent achievers who started out as pop-ups in the pandemic era. Entrepreneurs like Kuya Lord, Quarter Sheets, Villa’s Tacos, Poltergeist, and Azizam. Taste the cuisine at any of these places, and you’ll know something about the people who conceived the dishes. Their successes come with a reminder: No life follows a straight line.

Wang de Baroo, a dish of brandt beef short rib, burdock sauce, baek kimchi and ssam.

(Silvia Razgova / For The Times)

The open bar at Baroo's relatively new location in the Arts District.

(Silvia Razgova / For The Times)

At the old Baroo, I would sneak glances at Uh, standing alone in front of the stove in the small, cloistered room. I could never tell whether he looked brooding or on the verge of a breakdown. Probably both? Now I see him in his open kitchen surrounded by staff. He seems focused, but fundamentally happier. There is no naiveté here: running a restaurant is exhausting. But Uh and Park have transformed a short-lived legend into a working reality. That is inspiring in itself, and Uh continues to evolve in his craft.

With 24 hours’ notice, for example, you can order a vegetarian version of the tasting menu, which immediately becomes one of the most brilliant vegetable feasts in Los Angeles. The main course is bansang, a platter of bowls of wonderfully seasoned rice (no chorizo) and banchan of seasonal vegetables alongside evergreen treasures like dried acorn jelly with the thick texture of cavatelli. It’s a soup so deep and minerally, so unfathomable in its distillation of seaweed, mushrooms and other flowers, that one spoonful takes me back to the madness of Uh’s revelations of the past decade. The meal began with a “pine kombucha cappuccino,” a variation on Korean jatjuk that extracts the essence of pine nuts into a milky liquor. It was a reassuring start, and, in its depths, a bit mysterious. After all these years, in a triumphant return, one of our greatest culinary minds can still keep us guessing. As it should.

Baroo is the LA Times Restaurant of the Year for 2024.

The Restaurant of the Year will be presented to Baroo's Kwang Uh and Mina Park during this year's Food Bowl festival at Paramount Studios on September 20. Advance tickets go on sale this week at lafoodbowl.com.