Through April 7. The Ukrainian Museum, 222 East Sixth Street, Manhattan; 212-228-0110, theukrainianmuseum.org.

If you know the name Maria Prymachenko, it may be because in February 2022 Russian forces attacked a Ukrainian museum housing 14 of her paintings. People saved her art from the fire, and Prymachenko, a cultural icon in Ukraine, became an international symbol of a nation’s resilience.

In some ways this is fitting, as her exuberant art is allegorical and full of allusions to folk tales. But it may also have devalued her. If she was once “regarded as a benign and cheerful folk artist,” as one critic put it, she has more recently been seen as a beacon of hope against the war.

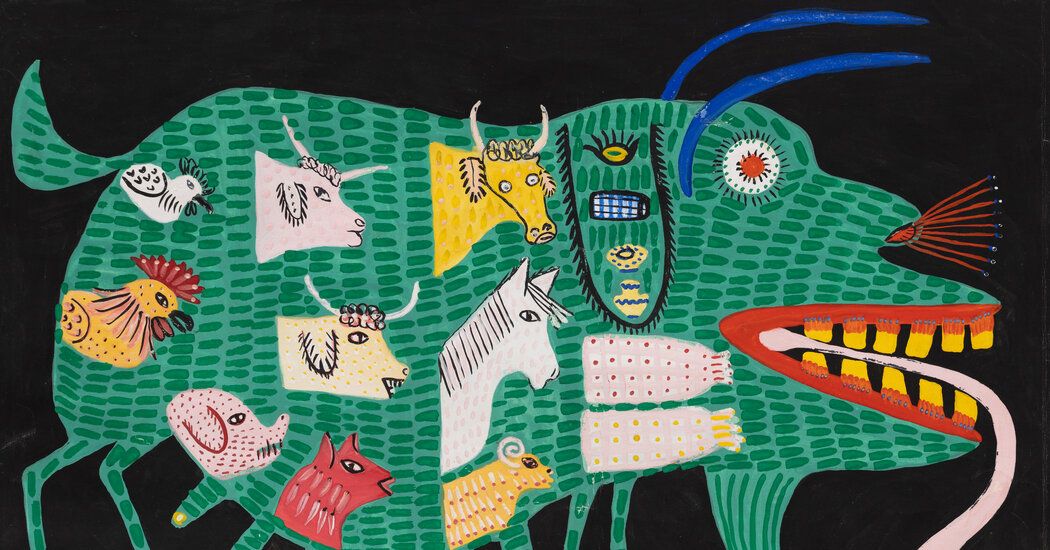

The exhibition “Maria Prymachenko: Glory to Ukraine” suggests a more complex reality. It is the largest exhibition of her work outside Europe and features more than 100 paintings, embroideries, ceramics and wooden plates. Prymachenko painted mainly flora and fauna, real and imaginary, from proud peacocks to eyed flowers and many-headed beasts. Her style is cartoonish; her works are patterned and repetitive, almost psychedelic.

Prymachenko, who was born in 1909 in Bolotnya, a village near Kiev, survived many things: polio, the Ukrainian famine of the 1930s, the deaths of her husband and brother in World War II, and Russification. You wouldn’t immediately notice it in her art, which vibrates with a playful energy, but there is also a mania in the surrealism of her images and the way her landscapes bloom almost eruptively. More pointed works, such as “War Is Horrible” (1968), which shows a beast filled with the heads of other animals, seem like the flip side of national anthems such as “A Ukrainian Palianytsia” (1984), which shows a couple holding the loaf of bread that gives the book its title. Prymachenko died in her hometown in 1997.

“Glory” is an appropriate word here, not in the patriotic sense of the programme’s title, but as a tribute to Prymachenko, whose talent proves to be rarer and more cosmopolitan than she is given credit for.

Khadim Ali

Through April 6. Aicon, 35 Great Jones Street, Manhattan; 212-725-6092, aicon.art.

Like Prymachenko, Khadim Ali also imagines creatures, albeit from a different time and place. The artist, who grew up in Pakistan near the border with Afghanistan, comes from a family of Hazaras, a group persecuted by the Taliban. As a child, he loved his grandfather reciting verses from the “Shahnameh,” an illustrated Persian epic poem. As a teenager, Ali worked on propaganda murals in Iran, before returning to Pakistan and studying miniature painting. Eventually, he moved to Australia.

These poetic and political influences can be seen in “The Birth of Demons,” his exhibition of paintings and tapestries. A series of delicate gouaches features a character with horns, wings and a flabby belly. He represents the defamation of Hazaras and other refugees, and is named after Rostam, a hero of the “Shahnameh.” At times, against a blood-red background, he seems trapped in wait, more pensive than gallant or menacing.

Ali’s tapestries, made in collaboration with Afghan artisans, steal the show. In these large, dynamic scenes, the traditions of miniature painting and mural painting are beautifully combined through embroidered silk. Two tapestries feature a tangle of cartoonish demons battling in the clouds. The third, “Birth of Demons 7” (2024), shows a clown leading a procession of angels carrying a soldier-god. Ali’s mythic world mirrors our own: glorified violence is as constant as the weather, and there are no heroes to come and save us.

Through March 22. Open Source Gallery, 257 17th Street, Brooklyn, 810-676-8723, open-source-gallery.org.

If our society is sick, Jody Wood proposes a partial treatment. Her “Social Pharmacy” project, launching in 2021, invites people to exchange remedies for physical and mental ailments. It is a small mobile structure with red walls and wooden shelves, on which items such as herbs, fruits and vegetables are placed. Each one has a label explaining what it is for and how to use it.

Some recommendations are simple (ginger tea to stave off colds), while others are delightfully abstract, such as a cinnamon stick prescribed “for overthinking.” The pharmacy is available 24 hours a day, seven days a week, through Wood’s “Collecting Health” exhibition, which also includes photographs, sculptures and videos. Visitors are invited to take something and, in turn, fill out a questionnaire describing a remedy of their own. The gallery staff stocks it.

Wood works in a lineage of social practice artists attempting to reimagine how we relate to each other and, by extension, the systems that govern those relationships. “Social Pharmacy” elegantly emphasizes that illness is not just a solitary affair, but is also tied to the health of others—a stark lesson from the coronavirus pandemic. By privileging communal knowledge, Wood seeks solutions beyond institutions—a double-edged remedy in itself. She began the project in New Brunswick, New Jersey, a city with many hospitals and low vaccination rates. Her video “Against Medical Advice” (2021) features impoverished residents at a soup kitchen talking about their distrust of the medical system. In the face of systemic inequality, community care is empowering, but limited.