LJ Rader tries to be online as much as possible during big sporting events, but he missed the first half of last Sunday's NFL playoff game between the Buffalo Bills and the Kansas City Chiefs due to a dinner commitment. After leaving the restaurant, Rader checked his phone and saw an unusual request: The NFL had tagged him on X, formerly known as Twitter, in hopes that he would submit one of their signature creations.

“I would have been really upset if I was still eating and missed this,” Rader said.

On social media, Rader is the wizard behind Art But Make It Sports, where he uses accounts on x and Instagram to combine photographs from the world of sports with paintings and other works of art that reflect them. Witty, irreverent and often moving, the accounts collectively have 365,000 followers.

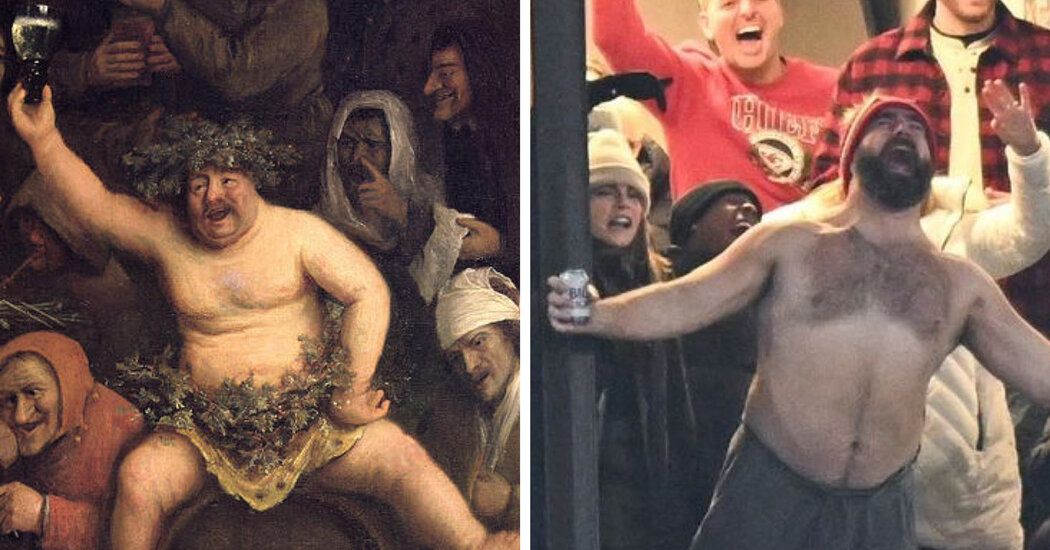

Last Sunday, the NFL wanted Mr. Rader's take on a scene that was destined for Internet immortality: Jason Kelce, an offensive lineman for the Philadelphia Eagles, was screaming, shirtless and clutching a beer can as he peered into a luxury box in the stadium. in subarctic weather to celebrate a touchdown his brother Travis had scored for Kansas City.

Rader did his own kind of mental math as he searched for the perfect piece of art to match the image: What was the most important element of the photograph?

“It's the fact that he's not wearing a shirt,” Rader said. “If I found a similar scene but the person was dressed, it wouldn't work.”

And then it occurred to him: “The Feast of Bacchus,” by 17th-century Dutch painter Philips Koninck, depicting the Greek god of wine and revelry in a half-naked, cherubic state of bliss.

“I did it,” the NFL wrote in response to the post, which has since garnered more than 95,000 likes on X.

Kathryn Riley, a Boston-based photographer who shot the image of Jason Kelce that Rader used, recalled the questions she asked herself when she saw the post: “How does this artwork line up so perfectly with the photo? And how did you know this work of art existed?

The Internet is a crowded place, but Rader, 34, has managed to do something new. Rader, a largely self-taught art aficionado from the Upper East Side, has taken advantage of his gift of instant memory to highlight the artistry and absurdity of sports. By identifying those parallels, he has brought fine art to a new audience while showing the art world that beauty and emotion can emerge in surprising places: on a soccer field, on an ice rink, or in a NBA bench.

Rader has compared a photo of an exhausted long-distance runner to a painting of Jesus Christ from the Baroque period. She has amplified the excellence of Michael Jordan through the abstract brushstrokes of Clyfford Still. She has used Salvador Dalí's melting clocks to underscore a tennis player's tantrum, compared a baseball player to a piece of taxidermy, and linked athletes to Rodin sculptures.

The pathos of those classic works of art is reflected in the sporting moments Rader chooses to highlight, and those comparisons only seem to elevate everyone involved: the artists, the photographers, and, of course, the athletes. “There is a sense that what happened 300 or 400 years ago is happening again,” Rader said.

The main difference is that this happens on a football field instead of inside a church.

“LJ brings art to the people,” said Bisa Butler, a contemporary artist whose work Mr. Rader has exhibited. She added: “It has often been said that the movements of athletes are as elegant as those of dancers, and LJ has gifted us with his vision of athletic beauty and fine art.”

Sometimes it's not so serious. Consider Rader's recent comparison between Mike McCarthy, the coach of the Dallas Cowboys, and “Mound of Butter,” a late 19th-century still life by Antoine Vollon. Rader said he wasn't making fun of McCarthy's size.

“It's just the same contour of his face,” Rader said, adding that Butter is “bland like his plays and, most importantly, melts like him every year in the playoffs.”

Mr. Rader said his grandmother, Judith Best, instilled an appreciation for art in him when he was a child in Katonah, New York. As a student at Vanderbilt, he took an art history course.

And while that was the extent of Rader's formal education on the subject (he now works as a product manager at a sports data and technology company), he continues to frequent museums and has about 10,000 images of artwork on his phone. (One of his folders is labeled “Meme Fuel.”) He also has a Substack, where he shares exclusive content with subscribers.

But when Rader started about four years ago, he simply pasted captions onto art images. For example, when the Knicks fired David Fizdale as their coach in December 2019, Rader included that news in a small caption at the bottom of “Salome with the Head of St. John the Baptist,” a 16th-century oil painting by Andrea Solario and one of the most elegant representations of a beheading.

Over time, Rader realized that instead of writing captions, he could simply combine the painting with a sports photograph. One of the first versions of that style was a moving photograph of Field Marshal Philip Rivers, which Rader combined with Francis Bacon's “Study for the Nurse in the Film 'Battleship Potemkin'.” The painting is of a naked and screaming woman.

The response, Rader said, was “overwhelming.” She had stumbled upon the magic of the Internet.

Why does it work? Sports and art tend to be seen as worlds apart, Rader said.

“But I think I'm showing that these two disciplines share a lot of similarities in terms of composition, emotion and talent,” he said, “and that maybe we're not so different after all.”

Like any insightful social critic, Rader can also be relentless. The Jets were in the opening minutes of their season opener against the Bills in mid-September when the television broadcast captured Robert Saleh, the Jets coach, on the sideline “looking like he really didn't want to be there.” Mr. Rader said. So he combined a screenshot of Saleh with Edvard Munch's “Self-Portrait in Hell.” The painting is more than 100 years old. The Jets finished with a losing record for the eighth consecutive season.

“I think the other theme that comes up a lot is that time is a flat circle,” Rader said.

He cited the Dutch early Renaissance painter Hieronymus Bosch as someone with whom he might not seem very identifiable. But Bosch's work, which Rader has analyzed for comparisons to college students knocking down a goal post, Nikola Jokic of the Denver Nuggets and a championship parade, conveys human emotions that are universal and enduring.

Angie Treasure, senior director of content for the Utah Jazz, recruited Mr. Rader last summer to help publish the team's 2023-24 schedule.

“He is a wise man,” said Mrs. Treasure. “I remember everyone being surprised when they found out I wasn't just running photos through an AI generator.”

As Rader's work has grown in popularity, speculation has spread among his followers (some more cynical than others) about how he goes about his business, including suggestions that he must be using artificial intelligence. Mr Rader said that was not the case at all. First, he said, his work predates ChatGPT and other artificial intelligence tools. Secondly, what would be the fun of using a computer?

“I do it for the fun of it,” he said. “It keeps me on my toes, gets me out of the house and takes me to different galleries, exhibitions and museums.”

In a video chat interview, Rader asked to be presented with a batch of sports photographs so he could be tested on the spot.

Amid a series of jaw-dropping comparisons, Rader needed about 2.7 seconds to compare a photo of “The Catch,” Dwight Clark's touchdown reception for the San Francisco 49ers in the 1981 NFC Championship Game , with “The intervention of the Sabine women.” an 18th century painting by Jacques-Louis David. In the painting, it is not the main subject that resonated with Mr. Rader, but rather a woman in the background holding a baby above her head while he engages her in battle. She (she could have been catching a football in the middle of a swarm of defenders).

Rader has a knack for remembering patterns and themes from works of art he has seen and studied, he said. That skill set doesn't translate to other facets of her life.

“I always forget my keys,” he said.