In our house, beauty had different names. This was in 1995, when we lived on 58th Place, in the upstairs unit of an ashen-white triplex in Ladera Heights, many miles south of the original glamor and beauty of Hollywood Boulevard. The beauty of our home didn't advertise itself the way it did in the movies I loved during countless family weekend trips to the Marina del Rey theater. There was no pomp or grand exposition behind its raison d'être. In our house, beauty simply existed.

Lately I've been trying to find my way back to beauty. On the precipice of turning 40, somewhere in the middle of this marathon of life, I want to exhume what I feel I have abandoned and lost. I want to remember what has been swept away by the pull of adulthood, what age and responsibility demand that we engage, that we let go. Again I want to remember what is worth finding.

So I turn to the past as a way forward.

Beauty was the configuration of my mother's deliberate care. It was love embodied in grilled cheeses and streams of laughter that ran through the house during unexpected moments of long tranquility. Beauty was also timidly situated, always in view of my and my brother's curiosities, like the framed print of “Jamming at the Savoy” by Romare Bearden that hung just outside the entrance to the kitchen I loved so much, that I sometimes wanted to live in, elegant and irreducibly cool like Bearden's jazz men.

Many years later, in graduate school, when I first read “Sonny's Blues,” a short story originally published in 1957 by James Baldwin about family and addiction, I remembered this painting, this house, and how its beauty stopped me. dry, how it challenged me to pause and consider my place in the wide world. “For while the story of how we suffer, how we delight, and how we can triumph is never new,” Baldwin wrote, “it must always be heard. There is no other story to tell, it is the only light we have in all this darkness.”

The narrator of Baldwin's story watches from the audience as his brother, a pianist, plays on stage. He is moved by what he sees, the beauty of everything. Baldwin understood it, as I would later. In a country that has never given much to black people, beauty was our right. Not physical beauty (although we also had the right to it), but made beauty. Beauty built from and for love.

Personalized. Tender. Yours.

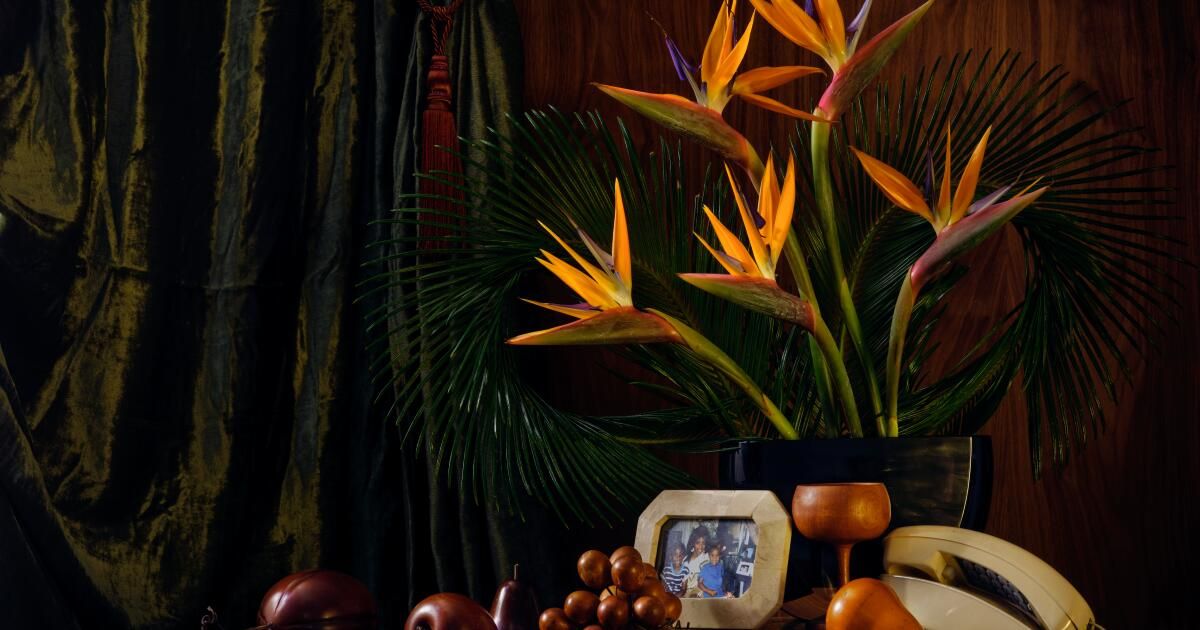

Most of the time, beauty appeared in a very specific form. At least once a month, my mother would pull birds of paradise from the bush below, arrange them like this, place them in a vase, and place the flowers as a centerpiece in the living room, on top of our mahogany coffee table. At the time, I was obsessed with Marvel comics and action movies like “Mortal Kombat” and “Batman Forever.” I didn't really know anything about flowers, but I knew this one was tough, with its sword-sharp silhouette and hellish orange color. This is how the bird of paradise first made itself known to me.

In most black homes, the living room is off-limits except on special occasions. Ours was no exception. In my opinion, this gave the flower a unique meaning. I secretly loved how the flower rose towards the sky, never diminishing its presence, what I considered its sharp elegance. It was something worth appreciating. In our home, it was not only beautiful, but it also gave meaning to our beauty.

Today, the bird of paradise is one of the predominant flora throughout the city. It also goes by many names (African desert plantain, crane lily), but formally it is known as Strelitzia reginae and is one of the five species of Strelitzia. “They were widely planted in the early days of Los Angeles,” Philip Rundel, a UCLA professor emeritus in the department of ecology and evolutionary biology, says of how the plant arrived in California.

Native to the KwaZulu-Natal provinces of South Africa in the Eastern Cape, the bird of paradise arrived at the Huntington Library, San Marino Art Museum and Botanical Garden sometime before 1932, when record-keeping began of the institution, he explains. Kathy Musial, senior curator of living collections. In the following decade, Japanese flower farmers grew them throughout the South; The species could survive on little water and stood up to five feet tall. In 1952, when Los Angeles celebrated its 171st year, the bird of paradise was designated the city's official flower by Mayor Fletcher Bowron, a Republican with an unpleasant appreciation for internment camps who would lose his re-election bid that same year. anus. (While state flowers are common, many cities also designate a specific flower as their local insignia.)

Often, despite its deteriorating political terrain, Los Angeles, like the bird of paradise, found a way to flourish. It grows “slowly but steadily,” Rundel tells me.

There it is, occupying manicured lawns in View Park, bordering the boulevards of Historic Filipinotown and Little Armenia. At Mahalo Flowers in Culver City and Century Flowers in Inglewood, the multi-use plant is ceremoniously adorned with floral arrangements purchased by customers. When it comes to regional emblems, only the palm tree seems to rival the bird of paradise in popularity.

“It is a very charismatic flower. Its shape and color are quite striking,” says Musial. I ask him what best personifies Los Angeles. I want to know what makes it special even though it is so common now. “It can adapt to a variety of growing conditions,” he continues. “It's a good symbol for a cosmopolitan city that hosts many human transplants, from other parts of the United States and around the world.”

Rundel suggests another interpretation. “It's a beautiful plant,” he says, “hardy and hard to kill.”

Yes, I think. That's all. Because isn't that beauty, in all its prismatic totality: hard to kill, always in bloom?

Everything I've learned since those years when we lived on 58th Place has stayed with me. What my mother had achieved was simple but lasting. The beauty we create establishes a sense of order. It grounds us in who we are, it gives body to our chaos. At its brightest and most spectral, beauty helps us endure.

And because the world, and one's continued engagement with it, is a repeated litany of small erosions, it is through the practice of beauty that we learn to survive, even to rise. It helps us find new and better ways of being. Yes, failure will make itself known. He will try to convince you that it is your only option. But it is the order we find in the beauty we create, in ourselves and in others, just as we find it in the things around us, that sustains and comforts.

Like the winged creatures of the sky that give it its nickname, the bird of paradise seems always ready to take off, leaning toward the light of a better tomorrow, or at least the possibility of one. It's what I remind myself when life gets difficult. Because although it was never guaranteed in our home, in the years after the rebellion, in those sometimes unsettled months as a new family of three amid the haze of my parents' divorce, we clung to the depth of that possibility no matter what. whatever came up. shape.

Now, as an adult and with everything that adulthood demands of the body and mind, I sometimes wonder: where can paradise be found?

I have learned that it is around us, but it is also within us. In the molecules of my memory, I cling to the punctuated beauty of the flower because I believe in what it can achieve, in what returns, in what leaves space. In the molecules of my memory it sings and what it sounds like is home.

It sounds like some kind of paradise.

Jason Parham is a senior writer at Wired and a regular contributor to Image.