YoIf you’re British and of legal drinking age, chances are you have strong feelings, one way or another, about Wetherspoons. Walk down virtually any high street in the UK and you’ll see the name: it may be shouted in capital letters from the roof of a city center pub, it may be written more discreetly on the entrance to a place that looks like an old drunk. style, or even outside a bank, an opera house or a renovated swimming pool.

It’s the gateway to a world of migraine-inducing rugs, oddly ornate toilets and shockingly cheap pints. Inside Spoons, you’re just as likely to encounter retirees eating curry or business types in suits having a quick meeting as you are a hen party or a group of teenagers sipping fluorescent cocktails by the fish tank, clutching their fresh facts. Identifications.

Last year, the company announced it had returned to profit for the first time since the pandemic, and its low prices attracted customers amid a cost-of-living crisis. In unrelated news, John Travolta also made headlines when he was spotted at a branch in Norfolk. He is also strangely beloved by millennials, many of whom will have come of age drinking from the aforementioned fish tanks in the heyday of 1990s binge drinking; on social media, strangers play the Wetherspoons game and buy food and drinks for people they’ve never met using the brand’s app (once you have the table and venue number, anyone can contribute from afar).

There are currently over 800 branches of this deeply generic but strangely idiosyncratic chain in the UK and Ireland, and each one is nominally different: each rug nods to the local area or the place’s past life (in 2016, writer Kit Caless public Spoon’s rugs: an appreciation, after traveling the country to document the different patterns). But the atmosphere is almost always the same, whether you are drinking at the “Super-Spoons” in Ramsgate, the chain’s largest venue with a capacity of 1,400, or in a converted church. Simple, uncomplicated, perhaps a little bland: a bit like frequenting an airport bar, but in your hometown. What could be controversial about that?

Turns out, quite a bit. Unlike most run-of-the-mill street shows – the Nandos, the Greggs or the Pizza Express – Wetherspoons provokes extreme emotions among the British public, often (but not always) drawn along culture war lines. And that’s largely thanks to its controversial founder, Tim Martin, who was awarded a knighthood in the 2023 New Year’s Honors List last month. Martin, 68, who is often pictured Dressed like a dad in vacation mode, with polo shirts and a pair of sunglasses over his shock of white hair, he has in the past become a seriously divisive figure in our national consciousness. almost a decade – the result of his long and unabashed support for Brexit during the 2016 referendum and beyond. His shiny new knighthood has served as a lightning rod for the great debate over Spoons: is it a haven of affordable, no-frills food and drink that’s practically a national institution? Or a cynical, heartless company lining the pockets of one of Vote Leave’s most prominent supporters? Is his title an example of cronyism in action or a recognition of a genuine contribution to British life?

The cult of Wetherspoons can be traced back to 1979, when Martin, then a solicitor studying for his final exams, became a regular customer at Marler’s, a pub in Muswell Hill; It was one of the only places in North London that sold the real ale he liked to drink. A few months later, he learned that the owner was selling and made a successful offer (according to DonThat offer was quite eclectic and consisted of “£40,000 in cash, a house in Putney and a two-week holiday in [Martin’s] Dad’s house in Jamaica. He reopened the venue as Martin’s Free House, but that incarnation didn’t last long: the following year the pub relaunched as JD Wetherspoon. The name was a strange amalgam: the “JD” is a reference to a character from the 1980s television series. The Dukes of Hazzard, while “Wetherspoon” was the surname of a teacher from Martin’s school days in New Zealand, who had struggled to keep his unruly students in line. “I thought: I can’t control the pub. [and] “I couldn’t control the class,” he said earlier, “so I’m going to name it after him.”

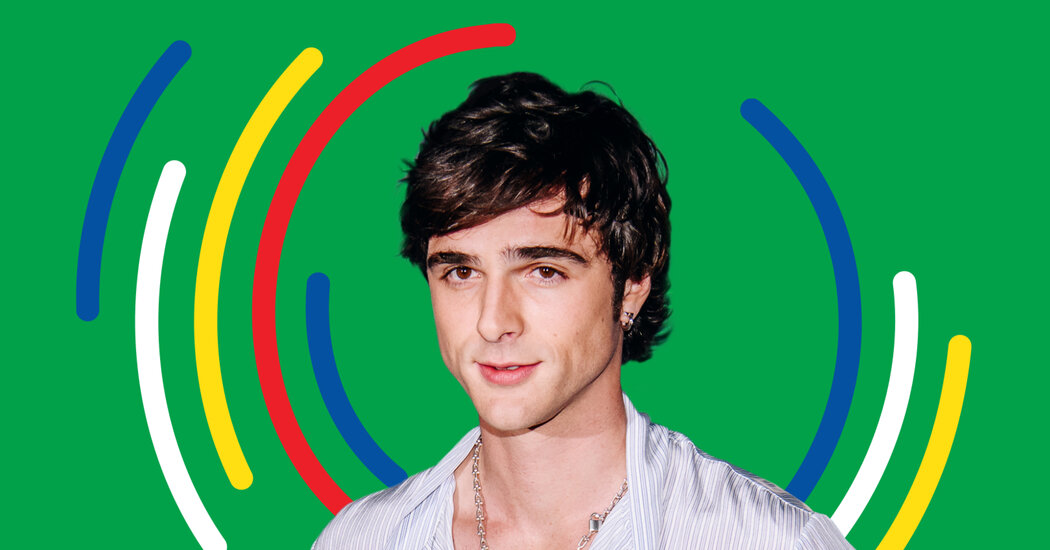

Knighted: Tim Martin’s new honor has caused controversy in some quarters

(PENNSYLVANIA)

An unexpected influence on Martin was George Orwell. In his 1946 essay “The Moon Underwater,” published in the Evening standard, the writer of 1984 and Farm He explained the characteristics of his ideal pub. This dream establishment, he wrote, would sell a “solid lunch” at a reasonable price; there would be no piano played or the hum of the radio heard, so “it would always be [be] calm enough to talk.” Orwell had many other stipulations (Victorian-style decor, pints served in pink china cups, and the ability to sell stamps, cigarettes, and aspirin, to name a few), but it was those two that Martin used as principles for his empire: He was so captivated by the writer’s pub philosophy that 13 of his establishments still bear the name “La Luna…”. You don’t have to go out of your way to be heard with music in a Wetherspoons (although the chain partially relented and installed televisions in its premises in 2006, coinciding with the World Cup). And you can always grab a cheap lunch: the classic Spoons stereotype is chips all day long, but these days you’ll also find vegetarian, vegan and gluten-free options on the menu.

It didn’t take long for Martin to start buying new premises: instead of taking over existing pubs, he looked for unusual sites, be they old post offices, motorcycle showrooms or cinemas. They were no longer tied to contracts with breweries, so he was free to seek out the best possible liquor deals and therefore charge customers less. It’s a tactic that’s been around for 40 years and kept prices low (there’s an urban myth that suggests Spoons buys beer close to its sell-by date to cut costs, but the company has described this as a “fairy tale”). ridiculous”) ).

Office for National Statistics figures published last summer showed that the average pint of beer in a pub now costs £4.56; Spoon prices tend to vary depending on which branch you drink at, but according to data collected by the food website. Pantry and Pantry In October 2023, a pint of Carling costs £3.35 on average. For Spoons devotees and defenders, this affordability is not only the key to a cheap night out, but it also turns these venues into a social hub of sorts, where patrons can still enjoy a low-priced meal and a talk, at a time when many are struggling with the cost of living. The flip side of this, of course, is that it’s hard to compete with rates like these, especially if you’re an independent publican still struggling with the fallout from Covid, labor shortages, rising fuel prices and supply chain problems. Is Spoons one of the last remaining high street “centres” because it is undermining the traditional pubs that locals used to go to?

Cheap and full of beer: Wetherspoons boasts some of the lowest prices on the high street

(PENNSYLVANIA)

And for some, low prices can’t mitigate the bitter taste left by Martin’s forays into political discourse. Spoons’ dichotomy goes something like this: he often presents himself as a kind of egalitarian space, but you could also say that he is a vehicle for right-wing populism. In 2016, Martin donated £200,000 to the Vote Leave campaign and eventually described the Brexit referendum result as a “new Magna Carta”. Hundreds of thousands of pro-Brexit beer coasters have been thrown in Martin’s pubs, detailing the potential benefits of leaving the EU and, later, urging politicians to rush to a deal; A few years after the vote, he banned European beers and abandoned champagne and prosecco in favor of English sparkling wines. He is also a regular at photocalls with the likes of Boris Johnson and Jacob Rees-Mogg; In 2020, Rishi Sunak’s smiling face appeared on some Spoons posters, which also used that incredibly embarrassing pandemic-era nickname for the then Chancellor, “Dishy Rishi” (Sunak had no involvement in the campaign).

Everyone, of course, is entitled to their own political views: it’s the fact that Martin seems so keen to spread them to his customers that tends to irritate Spoons’ detractors (who, in turn, tend to be painted as people who wring their hands and lack a sense of humor). Remoaners” of Brexit fans). And it seems a bit illusory to see these pubs in isolation as an unequivocal community asset, with Martin as a kind of unwitting philanthropist, when he has befriended political figures who have presided over austerity measures and cuts to public services. If Spoons has become a de facto social hub, you could say it is an indictment of the dire state of our society, rather than glowing advertising for the company itself.

The controversy, however, has hardly hurt Spoons’ position as Britain’s most ubiquitous pub chain. Martin’s status as a one-man sound bite generator has only boosted his public profile, and as the nation’s finances become increasingly squeezed, his brand’s low prices will only become more attractive to many. . Love or hate spoons, you certainly can’t escape them.