An immaculate metal box built in 1931 to symbolize the future bounced around the East Coast for decades before recently landing in Palm Springs for all to see.

The first American house composed entirely of metal and glass was once a prototype of experimental housing in New York. Now, the three-story, 1,100-square-foot Aluminaire House is the newest and oldest Albert Frey-designed structure in Palm Springs. The Swiss architect has been hailed as the father of desert modernism since he first settled in Palm Springs in 1934.

Cutout of Casa de Aluminarias in Mecánica Popular 56, No. 2, August 1931.

(Palm Springs Art Museum. Albert Frey Collection, 55-1999.2.)

“Here in Palm Springs, we often associate modern architecture with luxury, style and elegance,” Adam Lerner, executive director of the Palm Springs Art Museum, recently told an audience of 1,000 at the grand opening of the museum. structure as a permanent exhibition. “But with Aluminaire House, we are reminded that modernism is not just a style but an embodiment of ideas. “Modernism is about making good design available to a wide audience.”

Instead of retrofitting the house to meet current fire safety codes and the American Disabilities Act, the interior has been restored to its original condition but is inaccessible to the public.

“This is a little disappointing for us,” Lerner said, adding that the museum is raising funds to offer a virtual reality experience of the interior. The house is located on a closed site that is open during museum hours.

After the ribbon cutting, visitors walked through the door for a closer look at the Aluminaire House. Many tried the door handles and pressed their faces against the glass along the ground floor in vain attempts to catch a glimpse inside, while others opted for the view upwards into the stairwell, a gloriously beautiful composition. abstract of steel beams against walls in pastel tones, visible. through the double-height windows on its southern elevation.

“When Frey was in Paris working for [architect] Le Corbusier in the late 1920s,” says Joseph Rosa, historian and author of Albert Frey’s 1990 monograph of the same name, “was enamored of the methods of prefabrication and architectural standardization on display in Sweet’s Catalog,” a periodical. American policy on building materials and products that had shocked European architecture firms with its highly rational approach to mass-produced design.

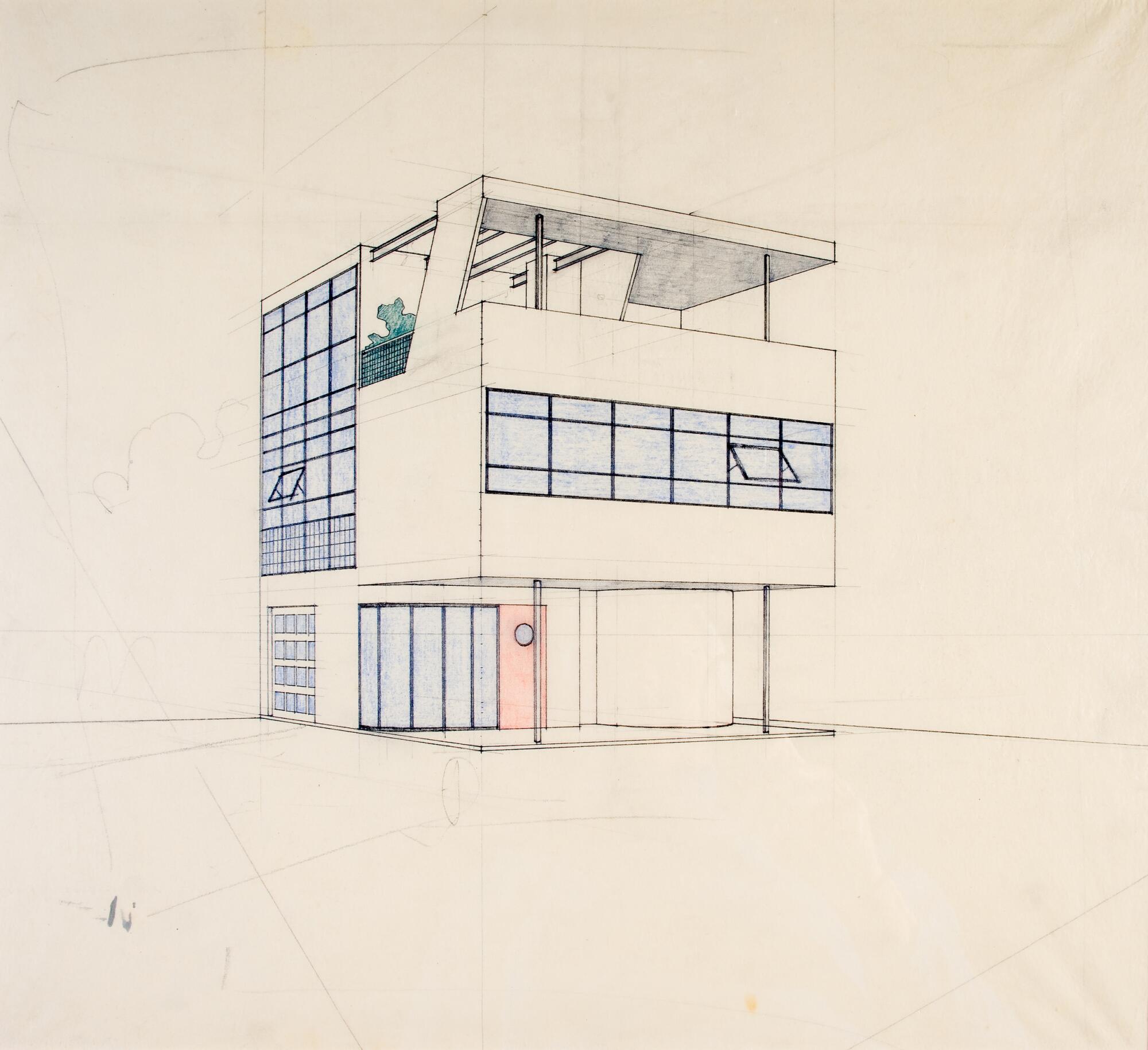

Hoping to combine the ideals of modern European design with American manufacturing capabilities, the 27-year-old Frey set sail for New York in 1930 and found a creative partner in A. Lawrence Kocher, editor-in-chief of Architectural Record magazine. who was then organizing the Allied Arts Exhibition: held the following year at the Grand Central Palace in Manhattan. “Kocher wrote and published, while Frey did the design,” Rosa says of his collaboration on the Aluminaire House for the historic event.

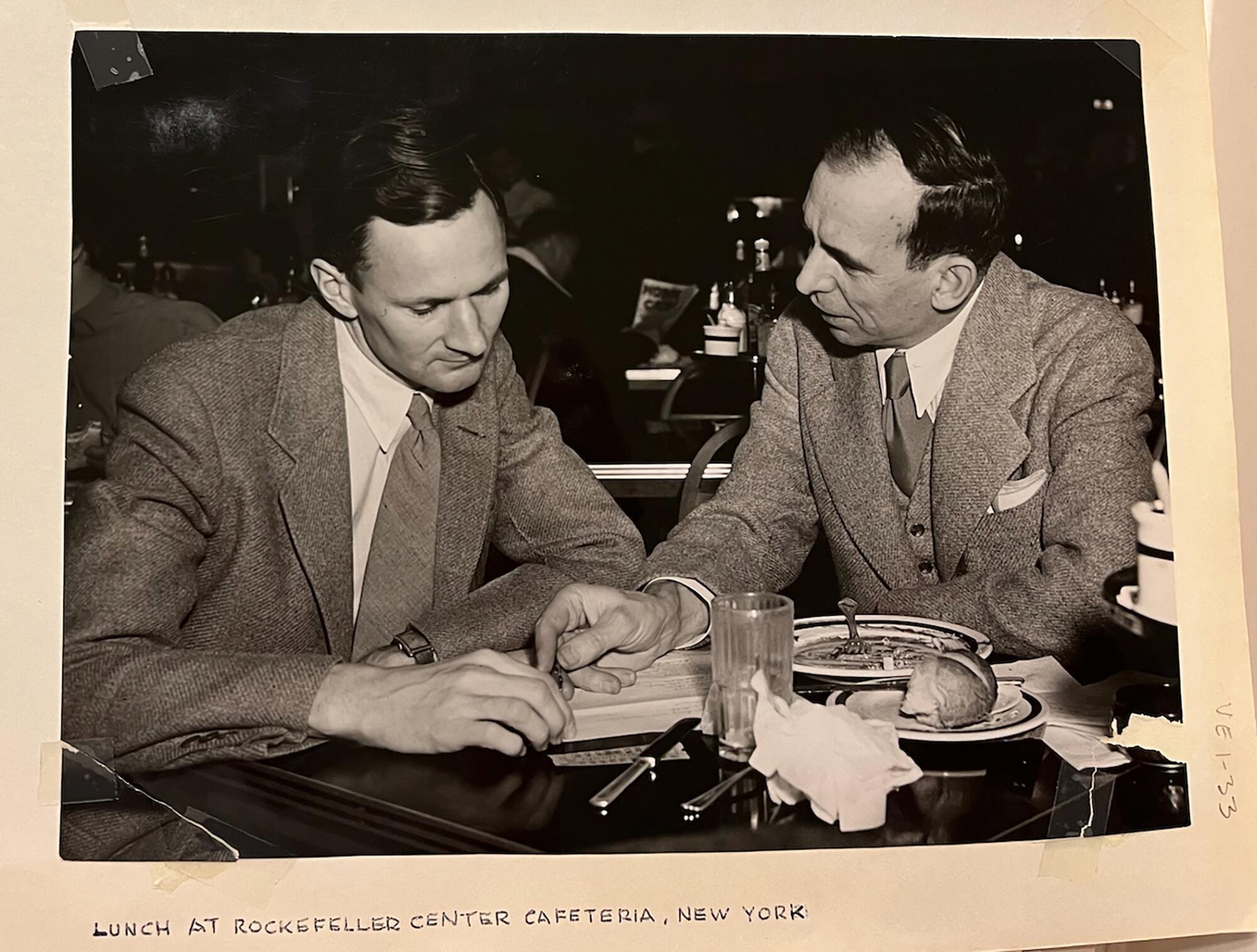

Albert Frey and A. Lawrence Kocher in the Rockefeller Center cafeteria, New York, 1931.

(Palm Springs Art Museum. Albert Frey Collection, 55-1999.2.)

The metal knob from Casa Aluminaire.

The Aluminaria House.

Frey wrote in 1988 that he and Kocher “had been discussing the need for low-cost housing in those Depression years. “We thought that a small, detached house, using new prefabrication methods and maintenance-free materials, would be popular with visitors to the exhibition and would offer a solution to the housing shortage of these times.” Aluminum was a lightweight but durable cladding material, and its cost had dropped considerably after the end of the First World War.

During the eight-day event, more than 100,000 visitors viewed its multifunctional interior features, which included integrated radios, overhead garage doors and a folding dining table. The surfaces were partially unfinished to reveal the steel structure and other new features unique to the structure. Visitors viewed the interior from the second-floor balconies of the exhibition space surrounding the house.

Architect Wallace K. Harrison paid for the model to be dismantled, moved to his Huntington estate on Long Island, and rebuilt as a second home for his family. Meanwhile, Frey took his passions to Palm Springs, where he designed several modernist structures throughout the region while touring the city in a convertible with a license plate that read “ALUMI.”

The Aluminaire House now stands at Museum Drive and Tahquitz Canyon Way, at the end of the long, winding road to Frey House II, the spartan home Frey built for himself in the hills in 1964 and bequeathed to the Palm Springs Art Museum after his death. in 1998.

The Aluminaire House at the Palm Springs Art Museum.

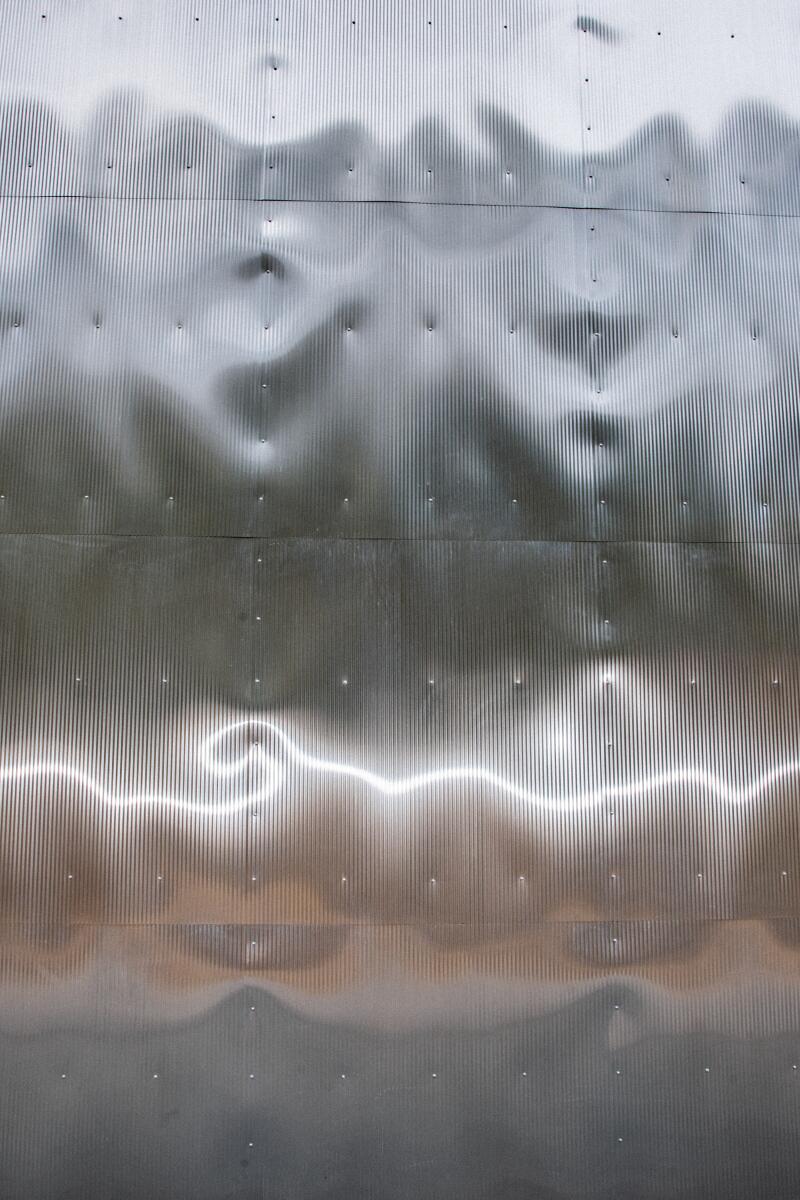

Details of the corrugated sheet metal cladding of Casa Aluminaria.

The Aluminaire House at the Palm Springs Art Museum.

Following Harrison's death in 1981, the Aluminaire House was headed for demolition before coming to the attention of New York Times architecture critic Paul Goldberger, whose 1987 article argued for the timelessness of its principles, if not its aesthetics. “At first glance, there is nothing particularly attractive about the House of Aluminaire,” Goldberger wrote. But here, “the dream that modernism would show a new way of life to the masses actually had a hint of reality.”

The New York Institute of Technology was soon asked to move the house to its campus in Islip, Long Island. “We decided to put it in the teaching curriculum,” said Michael Schwarting, a former professor at the institute who, with a $131,000 state preservation grant, brought architecture students to the site to dismantle the house before cataloging the elements. and transport them. inside a storage container. “A screwdriver and a wrench is pretty much all you need to take it apart,” said Frances Campani, a former high school professor who, with her husband, Schwarting, established the Aluminaire House Foundation. For many years, Schwarting design studios approached the Aluminaire House as a practical, large-scale case study for historic preservation.

In 2004, the house was dismantled once again following the dissolution of the Islip campus. As they struggled to attract New York-based institutions to assemble their kit of parts, Campani and Schwarting were invited by the organizers of Modernism Week, an annual celebration of midcentury modern architecture in Palm Springs, not only to give lectures about the Casa Aluminaire but also consider the city as your permanent home. A truckload of construction parts headed west in 2017, and a capital campaign seeking $2.6 million inspired local philanthropists to contribute.

“The entire structure we received is original from 1931, along with the doors, windows and stairs,” says Leo Marmol, a member of the museum's board of directors and managing partner of the Los Angeles architecture firm Marmol Radziner, who coordinated the team. design in place. Among the most challenging tasks was remanufacturing portions of the interior and exterior aluminum cladding and choosing their location near the museum's main building. The design team settled on a former car park at the south end, where its front façade now shines every morning at dawn.

Exterior perspective sketch of Aluminaire House, 1931, graphite, colored pencil on paper, 12 x 15 inches.

(Special Collections, John D. Rockefeller Jr. Library, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation)

Details of Aluminaire House's corrugated metal siding against a blue sky at the Palm Springs Art Museum.

Two blocks south, the exhibit “Albert Frey: Inventive Modernist,” on view in the museum's Center for Architecture and Design through June 3, lovingly depicts Frey as the creative soul of 20th-century Palm Springs while pointing out the first energetic sketches of the House of Aluminaire. .

“I can't think of any other city that has such a complete chronology of an architect's work from the first house he built in America to the last,” Brad Dunning, the curator, said during a public tour of the exhibition.

As an image, the Aluminaire House is, and will remain, as pristine as the day it opened in 1931. But as a significant attempt to build decent, affordable housing, a service sorely lacking in Riverside County, it is unclear whether Palm Springs You will feel the full weight of its new aluminum case. The Aluminaire House was more than an impenetrable monument to a style, and Frey knew that its purpose would be difficult for the masses to internalize, but could be accepted with instruction. “A proper education and explanation of the evolution of forms will accelerate the process of assimilation,” Frey wrote in his 1939 treatise, “In Search of Living Architecture,” “and make possible the simultaneous creation of modern media and respective forms.” “.