In 1984, a determined entrepreneur named Jules Dervaes Jr. brought his wife and children from a 10-acre farm in rural Florida to study theology in Pasadena, but ultimately decided to pursue a different ministry: creating a self-sustaining urban farm on a run-down residential property less than a block from the 210 Freeway.

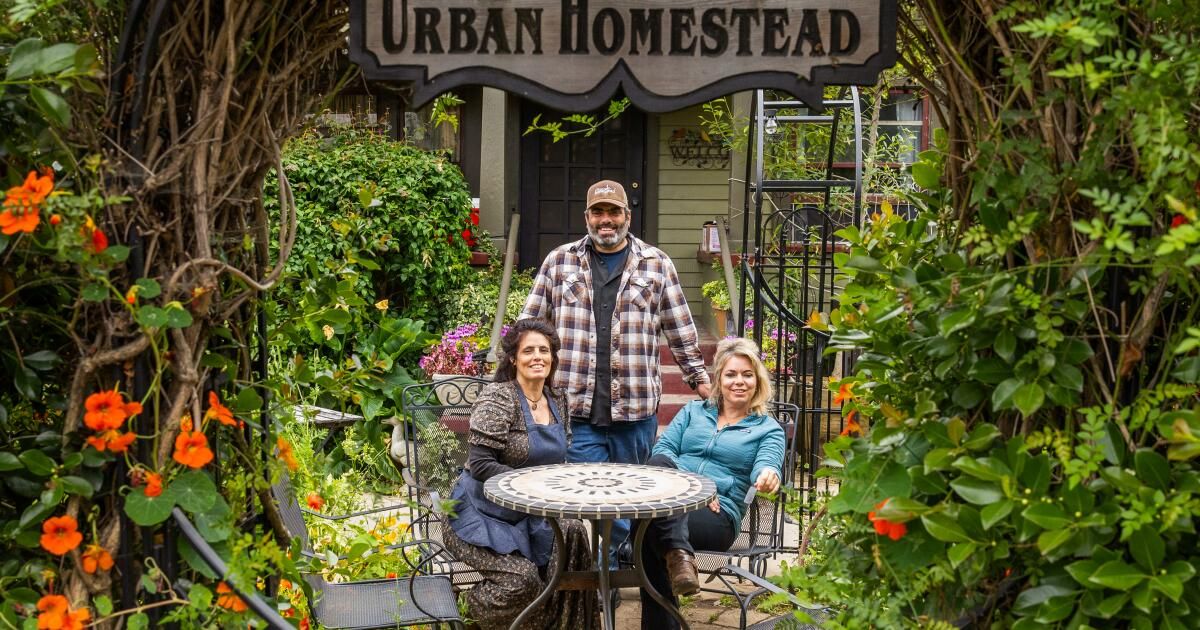

Jules Dervaes Jr. didn't have a long-term plan when he started an organic farm in the front and backyards of his Pasadena home, but he did have a vision of creating a simpler life that his children continue today, nearly eight years after his death.

His wife left shortly afterward (working on a farm was not the life she wanted to live), but their four children, now in their 40s, stayed and today three of the four still work on the farm known as Urban Homestead, providing produce and flowers to more than 100 subscribing families each week, along with several restaurants and catering companies.

“At first we just gardened to grow food for our family, but then Dad took up organic gardening as a business,” said Anäis Dervaes, the oldest daughter. “In 1989, we tore up our front yard, even the concrete, to grow more food, and our neighbors thought we were crazy, but the business took off, so we started growing organic gardens.” can “Make a living mowing lawns.”

And, as all farmers know, by working very hard.

Dervaes died in 2016 from a pulmonary embolism, but her children Anäis, 49, Justin, 46, and Jordanne, 41, continue to work on her vision. Through the Urban Homestead Institute, a nonprofit founded in 2001, they provide food boxes to families in need, offer internships to volunteers who want to help on the farm and welcome dozens of schoolchildren to see how real food is grown — a program that began after Dervaes encouraged Anäis to try a new activity called blogging in 2000.

It was a time of huge protests against genetically modified foods and Anais wanted to join the protesters, “but Dad said, ‘How about we write about what we do here every day, how we live a simple life? ’ And I think I said something like, ‘Should I write, ‘I harvested corn today? ’ Nobody’s going to care about that. ’”

But it turned out that people did. The family gained a following, and teachers at Compton High School wrote to ask if they could take some students to visit their urban farm. “We’ve been doing outreach with students ever since,” Anäis said.

Not as much as they would like, because space is so limited that they can only accommodate small groups. The garage is now a small warehouse and distribution center for food boxes. The covered patio is a place for classes, demonstrations, and their homemade pizza oven. The driveway is filled with trays of plant and flower seedlings. Chickens and ducks live in a rustic L-shaped structure out back, and fruit trees line the perimeter of the property. The rest of the yard is filled with raised beds densely planted with vegetables, herbs, and flowers, accessible by narrow walking paths.

Volunteer and client Tristan Lahoz, left, and Jordanne Dervaes tend to the densely planted flower beds at Urban Homestead.

Chef Onil Chibas, left, picks up his order of edible flowers and salads from farmer Justin Dervaes.

But you don't have to walk far to see a lot at Urban Homestead. Nearly every garden bed has dense plantings of something (lettuces, spinach, arugula, and red-stemmed dandelions, a tasty green for salads), dotted with sunflowers. There's a large compost-enriched soil bin where a hand-held seed-block maker is regularly used, allowing four uniform cubes of soil to be removed at a time that can easily fill a tray and just as easily be planted once the seeds sprout and grow—a vital tool when you're constantly harvesting and replanting.

The garden is alive with butterflies, bees and other beneficial insects, especially at the front, where flowers are the predominant crop, a jungle of red Flanders poppies and fragrant sweet peas (for bouquets) and sunny nasturtiums, marigolds and roses (for eating).

The Dervaes children aren’t getting rich, but they are making a living through long hours, low expenses and the courage to experiment. The family installed solar panels in 2003 and a greywater system that keeps their water bill under $1,000 a year. For a while, they even recycled cooking oil from local restaurants to make their own biodiesel for their diesel truck, and in 2009 they made a short film called “Homegrown Revolution” that won awards at several film festivals.

A few years ago, they used a rent-to-own plan to purchase a neighbor's house two doors down and expanded their farm into the front yard. Jordanne and Anäis live there now, while Justin lives in the main house, overseeing the main farm operation and renting out a couple of rooms.

Anäis describes herself as the “cook and educator,” making products like jams and teaching workshops on knitting and other homemaking skills. Jordanne, the youngest, oversees their beehives (which are kept elsewhere) and flock of chickens and ducks, a job she’s had since she was a child. All three do outside consulting on various aspects of gardening, farming, and chicken raising, which led Occidental College to hire Jordanne to teach a popular class on regenerative gardening and sustainable animal care, with occasional input from her siblings. And Jordanne recently earned her real estate license to pursue her interest in preserving old homes.

Urban Homestead's poultry feed on much of the farm's garden waste and provide plenty of nutrient-rich droppings to feed the soil. Their eggs are an added benefit to the family.

Anäis Dervaes tidies up the kitchen of her family home, built in 1917.

But the family farm remains their main focus and keeps them so busy that it interferes with their love lives, Anais said. All three are single and would like to have long-term relationships someday, but it's hard to find people who share their priorities.

“Love life is something we haven’t mastered yet,” Jordanne said with a laugh. “I can take on any challenge, but this one baffles me.”

It's partly a matter of timing and partly a matter of priorities, Anäis said, like when he gets frost warnings on his phone and has to cut short an appointment so he can rush home to cover crops and protect them from damage.

“We live as farmers in the city, so we see things differently than most city dwellers, and they don’t always understand that,” Anäis said. “But this is our livelihood; this is our life.”

It wasn't always great, she said. They became a vegetarian family when they were very young, and as teenagers, they all had rebellious moments. They were home-schooled, but neighborhood kids teased them for what they were missing out on: Nike sneakers, hamburgers and canned soda.

“We were kids eating cereal and running around barefoot in the street, and I felt like I didn’t fit in,” Anais said. “I would say, ‘Dad, why do we have to shop at thrift stores? Why do we only eat food from the garden? Why don’t we eat regular stuff instead of chard?’”

A plaque commemorates Jules Dervaes Jr.

Handcrafted jams are available at Urban Homestead.

But once she read the book that inspired her father’s vegetarianism, John Robbins’ “Diet for a New America,” “it was like a light bulb went off,” she said, “and this lifestyle became mine.”

It wasn’t like their father forced them to do what they didn’t want to do, Jordanne said. “We had a lot of resistance, but he always encouraged us to question everything in our lives,” she said. “And we had responsibilities. There was a sense of pride in growing all these plants, and the business was ours. Dad always said, ‘If you want to do it, read about it and do it.’ He challenged us to learn and solve our own problems.”

There were some limits — Jordanne’s desire to own a horse and a cow was simply not possible — but ultimately it was the freedom to experiment that drew them back each time they strayed, Anäis said. “There was a sense of identity and family survival here. It gave us purpose and passion. I would plant on the moon if I had to.”

The farm is open to visitors on the second Sunday of every month for two-hour “learning tours” (tickets are $75). But Justin has some advice for people who want to tear up the lawn and become urban microfarmers, or simply design food gardens.

Salad mix seeds planted at Urban Homestead.