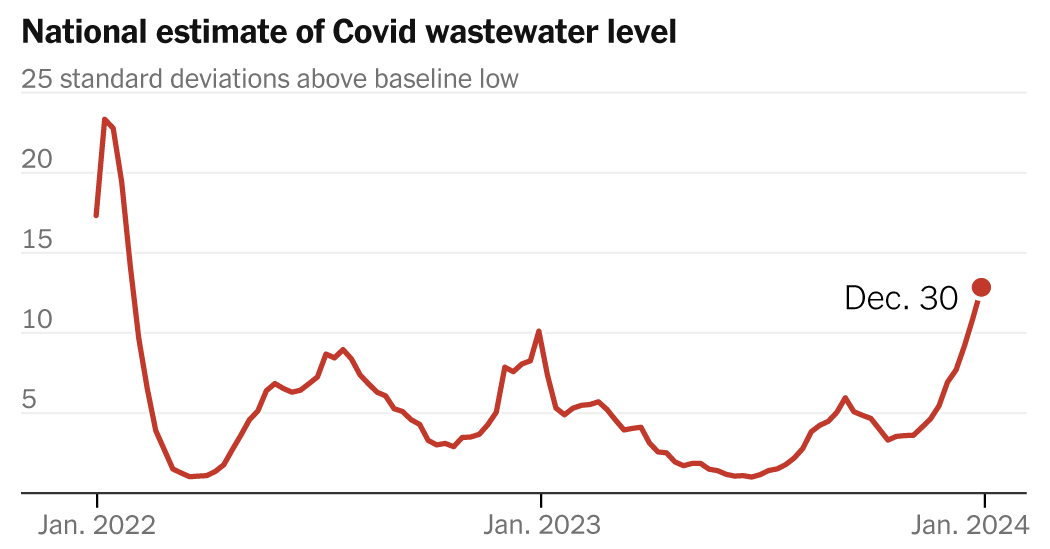

The curves on some Covid graphs look quite steep, again.

Reported levels of the virus in US wastewater are higher than since the first wave of Omicron, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, although severe outcomes remain rarer than in winters previous pandemics.

“We're seeing rates increasing across the country,” said Amy Kirby, program leader for the CDC's National Wastewater Surveillance System. The program now classifies each state with available data into “high” or “very high” viral activity.

The surge could peak this week or soon after, modelers predict, and high levels of transmission are expected for at least another month.

Hospitalizations and deaths have remained much lower than in previous years. About 35,000 hospitalizations were reported in the last week of December (up from 44,000 the previous year) and 1,600 deaths were reported weekly in early December, up from 3,000. (At the same time, in 2020, there were about 100,000 hospitalizations and 20,000 deaths each week.)

Many of the metrics used early in the pandemic have become much less useful indicators of how widely the virus is spreading, especially since federal officials halted more comprehensive data tracking efforts when they declared an end to the health emergency. public last spring. Greater immunity across the population has meant fewer hospitalizations even with high virus spread, and the sharp decline in Covid test results reported to authorities has made case counts much less relevant.

Wastewater testing remains one of the few reliable instruments still available to monitor the virus. It can signal the start of a surge before hospitalizations begin to rise, and includes even people who don't know they have Covid. For many who remain at higher risk of contracting the virus, such as those who are older, immunocompromised or already have a serious illness, it has become a crucial tool to help them understand when to take extra care.

But it is an imperfect metric, useful primarily for identifying whether there is an acceleration in the spread of the virus, not for saying exactly how much virus is circulating.

The data is often reported as normalized viral copies per milliliter or per gram, a number that is nearly impossible to translate into accurate case counts, experts say. It's also difficult to know how comparable two different surges are: a spike in data may not mean exactly the same thing this year as it did last year.

That's why many scientists who study the data will only say that it shows the nation is in the midst of a major wave, not whether this winter's surge is larger than previous ones.

(The CDC does not show actual concentration levels; instead, its dashboard shows how much they have increased relative to when spread was low. Above eight standard deviations is considered “very high.”)

Wastewater testing doesn't work because “everybody poops,” said David O'Connor, a virologist at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Wastewater samples are captured at or on the way to treatment plants and analyzed for viral RNA in a laboratory. But no two samples are perfectly comparable. The amount of RNA in the sample will fluctuate depending on many factors, including the local population at a given time (think a vacation rush to Miami or a college town that empties during the summer) and the amount of other materials, such as debris. industrial, it is in the system.

What experts really want to know, said Marisa Eisenberg, a University of Michigan professor who runs a wastewater monitoring lab at five sites, is how much virus there is relative to the number of people around — the wastewater equivalent per capita. case count.

Some labs “normalize” the data (that is, adjust the denominator) by looking at the number of gallons flowing through the plant, Professor Eisenberg said. But many sites use something called “pepper mild mottle virus,” a virus that infects pepper plants.

“People have studied this in human wastewater and found that we removed fairly consistent levels of this pepper virus,” he said. “So that's a measure of how many people went to the bathroom in the sewer shed today.”

Once Professor Eisenberg's team normalizes the results, it sends data to the state and the CDC, which collects information from sites across the country that together represent about 40 percent of the U.S. population.

The CDC then aggregates its data and publishes state, regional, and national trends. (Two companies that analyze wastewater, Verily Life Sciences and Biobot Analytics, also aggregate data from hundreds of sites and provide national and local pictures of the virus's spread.)

But those national-level estimates can be complicated.

The population sample the CDC analyzes largely excludes people with septic tanks and cities without wastewater testing. There may be gaps in the data, like when the CDC changed contractors last year. Existing sites may stop testing and start new sites as the network changes and expands.

And while Biobot and Verily may use the same methodology and standardization across all of their sites, the CDC has to determine trends from data coming in from different sites with a variety of methodologies.

Finally, there are changes to the virus itself that could make comparisons over time difficult. Scientists tracking those changes say there are signs that this latest variant, JN.1, might replicate better in the gut.

It's still just a hypothesis, said Dr. O'Connor, the virologist. But the virus may be “a little more welcoming in the gut” than it used to be, he said. If the hypothesis turns out to be correct, it could mean that infected people shed more viral copies than before. In wastewater data, the same number of infections could look like much more Covid.

All of that together creates significant uncertainty about how comparable the data is from year to year.

Michael Mina, epidemiologist and scientific director of eMed, estimates that the actual amount of Covid spread could be significantly higher or lower than this time last year. But there is no doubt that there are many viruses, he said. And much more now than just a few months ago.

Many experts who study this data recommend abandoning any notion of precision and simply squinting a little at the line's recent trajectory. And, if possible, look at your city's wastewater, since data from a single site tends to be more reliable over time than a national estimate.

“If you have vulnerable people in your community or family, you should be particularly vigilant when cases rise and take extra precautions,” Dr. Mina said. “And when cases are declining or calm, relax those precautions.”

Those precautions include wearing a high-quality mask, getting vaccinated, getting tested and staying home if you are sick, and if someone at high risk is infected, taking Paxlovid.

Even in this new pandemic phase, people are still dying and can still get Covid for a long time, said Maria Van Kerkhove, technical lead on Covid at the World Health Organization. “While the Covid crisis is over, the threat is not,” she said.